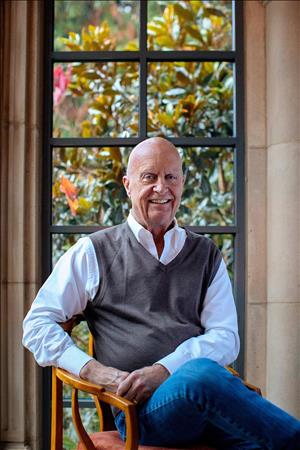

Allen Shoup (1943-2022) was a Washington wine industry pioneer who helped create a national market for Washington wines, and for Chateau Ste. Michelle wines in particular. Shoup was a top business executive at Amway, Max Factor, and other companies before landing in the wine industry in California with Ernest & Julio Gallo. In 1980, he was hired by the Chateau Ste. Michelle winery in Woodinville. In 1983, he became CEO and was responsible for making Chateau Ste. Michelle one of the biggest wineries in the U.S. In the 1990s, the Washington wine industry had branched out into fine red wines and Chateau Ste. Michelle had become a major player in the U.S. wine industry. Shoup left Chateau Ste. Michelle in 2000 and opened his own winery, Long Shadows Vintners, in Walla Walla. At Long Shadows, Shoup collaborates with renowned winemakers from around the world to make some of Washington’s most respected high-end wines. Here, in an August 29, 2022, interview with HistoryLink’s Jim Kershner at Shoup’s home in Shoreline, he describes how his Gallo experience prepared him for the challenges he faced in gaining recognition for a Washington wine industry still in its infancy.

Getting the Word Out

Allen Shoup: Gallo understood the importance of a really well-trained, highly disciplined sales organization. I knew that was going to be important. In the beginning, I put more money into public relations than I did sales because we couldn't sell something that nobody knew about; we had to build the awareness and we had some very aggressive and unique programs to build awareness. The thing about it, and it's funny, there's a lot of wineries that still don't understand this, even today, that are struggling and don't understand, there is an industry out there called wine writers, and they need stories, and to not feed your information into those. And so we found very successful ways to feed it. We did major luncheons, we did San Francisco, L.A., and New York. That's where most of the major wine writers lived, in those three areas. In each case we would find one of the best restaurants, one of the hardest restaurants to get into, that wasn't open for lunch and we would get them to open for a lunch because we were going to bring all these writers in, food writers, as well as wine writers. We'd do a luncheon that would be built around our wines, and they were phenomenally well attended and it was a wonderful way to show off your wines because you have this great food. There's nothing to make your wine taste better than really quality food, that goes both ways. So that's what we did ... we were promoting Washington.

In one instance in 1993, this strategy of attracting attention paid off spectacularly well with the national media in New York. It wasn’t simply good for Chateau Ste. Michelle. It was good for the other wineries as well.

AS: I can remember carrying other better Washington wines to New York. Bob Betz and I spent a week in New York one year, visiting Time magazine and all the others. Mostly we took them to lunch at the Oak Room in the Plaza Hotel. It was set up ahead of time, we had a local New York PR person to get these appointments set up. We were showing everybody's wine, trying to get different stories, because we knew that they weren't going to give us a commercial. Time magazine wasn’t going to write about something [just because we gave a luncheon]. And we did, we got a two-page article in Time magazine.

That June 27, 1983, article in Time was titled "Washington’s Bright New Wine" and it was a turning point in getting national recognition for the wines of Washington. The article singled out the Columbia winery, which was not one of Shoup’s labels, but the publicity for the entire Washington wine industry was priceless. At the time, however, Washington and Chateau Ste. Michelle were still known mostly for white wines, Riesling in particular. Chateau Ste. Michelle continues to be one or the world’s leading Riesling producers, but Shoup has always regretted some missed opportunities in that area:

AS: We didn't see Riesling as a future because it was a unique Washington phenomenon. The Riesling wasn't selling anywhere else. It was always, I think, too bad, because I think the Chardonnay thing took off and people started thinking that good wines have to be oaky and dry. Heavy oaked Chardonnays were really popular for a while, until people suddenly realized, it's really not too hard to do. It's harder to make a great Chardonnay, a more delicate Chardonnay, without too much oak. We wanted to get people buying our Chardonnay, get people buying our red wines. We literally stopped marketing [Riesling]. Oh, we sold it. We sold it. We were certainly the biggest Riesling [producer]. If you were going to sell Riesling, and everybody had to, then you would sell ours. But you wouldn't sell much.

Shoup always believed that if American wine drinkers had discovered Riesling before Chardonnay, Riesling would have become a natural choice for many. Eventually, Shoup and Ste. Michelle figured out a way to market a fine Riesling in collaboration with Dr. Ernst Loosen, a renowned German Riesling maker. Here Shoup talks about how Chateau Ste. Michelle’s fine Riesling label, Eroica, came about:

AS: [Ernst Loosen] said to me, he says, "I believe there'll be a renaissance in Riesling, but it's not going to happen in the old world. It's going to happen in a new world. It's going to either be United States or Australia." And I had been to Australia, and I saw already what was happening there, so I was really hoping he would do it here and work with us. And so we jumped at the opportunity and that was a success because we had created this thing called Eroica ... We produced 20,000 cases of Eroica, and we marketed it at $24 a bottle, and we had never sold Riesling for over $10 a bottle. And overnight, it was sold out. From a financial standpoint and everything, it was just a great, great success, so that was exciting.

Red wines – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah – eventually became the drivers of Washington’s wine industry. Deep into Shoup’s tenure at Chateau Ste. Michelle, the winery had earned enough market share to command respect nationally. By the early 1990s, Chateau Ste. Michelle became a “major player in the industry,” in Shoup’s words. Here, he describes the turnaround:

AS: In the early days we had to pick distributors who were willing to sell us. I remember stories of going to Chicago, for example, to meet with our Chicago distributor, and waiting out in the office, waiting for my appointment. All of a sudden Bernie Fetzer [prominent California winemaker] walks in out of nowhere, and the people went to lunch with him. Didn't even see me. That same distributor, about five or six years later, would send a car to the airport to pick me up. We became big enough that we were a very important player.

When Shoup left Chateau Ste. Michelle in 2000, he realized his dream of starting his own high-end winery, Long Shadows Vintners. The concept was to have different winemakers from around the world come in and use their talents to create versions of their specialties using Washington grapes. Here, Shoup describes how he sources the finest Washington grapes possible:

AS: The reality is that what you can get depends on price points ... Long Shadow wines are $60 a bottle and above. You can pay what you need to pay for fruit. Growers build their reputation around the wines, around their grapes going into 100-point wines and things like that. If they can do that, then they can charge more for the grapes. Growers want producers who can do that. The producers want growers who try to create those kinds of wines. So we have no problem finding the fruit. We'll pay what we need to pay to get it.

Here Shoup describes building the Long Shadows winery in 2003:

AS: It's a state-of-the arts facility, 30,000-square-foot facility. Each of these winemakers, I said, "You tell me what you want." I started with quite a bit of money. My own and some with investors and everything. But I know that wineries go under because they don't capitalize. They don't realize that you need three years’ worth of capital. You make the wine and sit on it for two years before you can sell. There are very few products like that. If you're growing, that keeps expanding, the amount of wine you're sitting on. So, I told them, I said, "Grow whatever you want. I'll buy it." With Michel Rolland, he wanted these huge, upright, French oak fermenting tanks that cost $25,000 a tank. You can get a stainless-steel tank for a fraction of that. They're good for five years, where stainless steel is good for 1,000 years. But that's what we did. We bought those tanks.

When looking back at his lengthy career, Shoup feels as if he was especially fortunate to arrive at Chateau Ste. Michelle when it had a lot of capital to invest, and at a time when the Washington vineyards were just beginning to reach their potential. Here he describes his good fortune and good timing:

AS: I don't know if it sounds like false modesty or what, but I just always felt I was very lucky. I was lucky to be given the opportunity. I didn't deserve that luck; I didn't do anything to earn it, it just happened ... I was saying that, in my case, I had all this money to work with. It helped me. But the other thing that none of us knew, none of us, was that back when this started going -- up until probably 1990 -- none of us knew that the viticultural region was as good as it is. A viticulture region needs 10, 20, 30 years of wines to prove this. We didn't know it then. We didn't know ... Absolutely, it couldn't have happened without that. That's the single biggest phenomenon, was discovering that. That took us out a long time to figure out how take advantage of this viticulture region.

Further Reading: HistoryLink's biography of Allen Shoup by Jim Kershner.