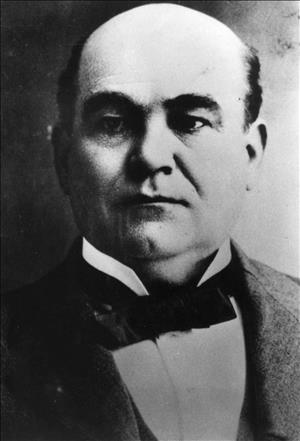

Samuel Cosgrove served as Washington's sixth governor for two months between January and March 1909. Seriously ill with Bright's disease – persistent kidney inflammation that today is known as glomerulonephritis – Cosgrove insisted on being ceremonially sworn in and giving a short inaugural address to the legislature on January 27, 1909. He left Olympia two days later to convalesce in California but never returned, dying two months after his inauguration. He subsequently became known as "Washington's One-Day Governor," but this overshadows the larger story of the man and his decades-long determination to become governor of the state.

Beginnings

Samuel Goodlove Cosgrove was born April 10, 1847, in Tuscarawas County, Ohio, the son of Elliott Cosgrove (1814-1897) and Emily Berkshire Cosgrove. He was the sixth of 12 children, and at some point during his childhood the family moved to Delaware County, Ohio, where he grew up on the family farm. He ran away from home at the age of 16, in 1863, when he was unable to obtain his father's permission to join Union forces in the Civil War. He enlisted in the 14th Ohio Infantry Regiment and served until the war ended in 1865.

After he returned home, he told his parents he wanted to attend college. This was considered a luxury by many in the nineteenth century, and certainly unnecessary for a farmer. This included his father, who not only refused to support him but – according to Cosgrove years later – kicked him out of the house when he turned down his father's offer of an 80-acre farm. It left a rift between father and son that never healed, but it instilled a determination to succeed in the young Cosgrove. He taught school for several years to pay for his college costs, and graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1873. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1875 and practiced law for several years.

He also continued teaching. On June 25, 1878, he handed out diplomas to graduating seniors at a Cleveland high school where he had taught for several years. As the ceremonies appeared to be ending, Cosgrove asked for the audience's attention. He explained that the program was not quite over, and asked a minister who had assisted with the ceremonies to come to the stage. He next called one of the students, Zephorena ("Zeffie") Edgerton (1858-1949), to the stage. The minister married them on the spot. Three children followed: Howard (1881-1936), Elliot (1883-1958), and Myrn (1885-1963).

A Natural Politician

Cosgrove left Ohio in 1880. He spent a year mining in Nevada and another year in California before moving to Pomeroy in Garfield County in 1882. He practiced law in Pomeroy and served five terms as mayor of the town. A gregarious man who was a natural politician if there ever was one, he had an ability to befriend whomever he met, from high-level politicians to odd-job laborers. Cosgrove liked people, and people liked him. It was perhaps natural that he would go into politics, and even in the 1880s he made no secret of his ambition to one day be governor of Washington.

Cosgrove served on the Washington State Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1889 and helped draft the constitution that led to Washington becoming a state that November. He was a presidential elector in 1900 and 1904, and was offered a seat on the state supreme court in 1904, which he declined. He was happy to serve in the back rooms of Republican politics for much of his career and put the party-preferred candidates out front. His ambition to be governor remained well known, but no one took it seriously – at least, not at first.

He didn't limit himself to politics. It was an era when fraternal connections carried more weight than they do today, and the affable Cosgrove had plenty of them. He served as the department commander for the Grand Army of the Republic (a fraternal organization made up of Union Army veterans from the Civil War) for Washington and Alaska, and as a junior vice-commander-in-chief for the national organization. He was a Mason and an Elk, and he was especially active in the Odd Fellows, one of the largest fraternal organizations in the country at the turn of the twentieth century. Cosgrove served as grand master of the organization in Washington for a number of years.

Golden Opportunity

Early in 1907, the Washington State Legislature established a direct primary system for candidates for state office, who would now be chosen in a public primary; they had previously been nominated at party conventions or, rarely, by petition. It was the opportunity that Cosgrove needed to make his try for the governor's chair. He wasted no time setting up offices around the state, later establishing his headquarters in Seattle as the primary date grew near, and getting acquainted with the people. He made his closing speech in Ballard three days before the primary, remarking, "This campaign has been a long and bitter one, and the feelings of candidates have not been spared by their opponents. But neither from the press nor the platform has come one statement that I may not be counted upon to keep my word" ("Cosgrove Makes ...").

With just over 25 percent of the vote, Cosgrove had the largest total in a field of 13 candidates (both Democratic and Republican) in the governor's race in Washington's first primary election on September 8, 1908. Though many candidates had small vote totals, Cosgrove faced more serious competition from the current governor, Albert Mead (1861-1913), as well as from the previous governor, Henry McBride (1856-1937). He defeated the two men, who were also Republicans, by margins of less than 4 and 5 percent respectively. But all was not well as he entered the general campaign. It was known that he had what was then called Bright's disease, a serious kidney ailment which could prove fatal. However, he had been in good health until the campaign, which taxed him to the point of utter exhaustion and caused his condition to worsen. By mid-October he was off the campaign trail, and by the end of the month, The Seattle Times was publishing articles raising alarm about his health.

If these concerns had any effect on the vote, it didn't show. In the November 3 election, Cosgrove won more than 62 percent of the total, nearly double that of his closest opponent, Democrat John Pattison (1859-1928). It was part of a broad Republican sweep in statewide politics in 1908. He gave a brief statement three days later, thanking his friends for their efforts, promising a "clean, just, and able administration," and optimistically concluding "as I scan the political horizon I believe we will unite to carry out an economical administration for the whole state" ("Governor-Elect Thanks ...").

Health Struggles

The next day, The Seattle Times reported that Cosgrove was near death. He had planned to go to Paso Robles, California, after the election to rest and to take advantage of the area's mineral hot springs, which were believed to have health benefits, but he initially was too ill to travel. Governor Mead met with Cosgrove in Pomeroy on November 10, and Cosgrove suggested that Mead continue to carry out his responsibilities as governor so Cosgrove could focus on his recovery. This was a practical suggestion in more ways than one. The state constitution prohibited Cosgrove from becoming governor if he was out of state, even if temporarily, and Mead would have remained governor in any event. (If Cosgrove had died before being inaugurated, Mead would have carried on as governor until an election could be held.) Mead was happy to agree, and even offered to follow the governor-elect's plans and policies in the interim.

Cosgrove departed for Paso Robles on November 12, stopping to rest at hospitals in Walla Walla and Portland. Upon arriving in Paso Robles he seemed to improve, but in early December his condition abruptly worsened. At one point, he was not expected to live for more than 24 hours. Then he began to improve again. By the week before Christmas the news reports from California were more hopeful, and by New Year's Eve even The Seattle Times was optimistic, reporting that Cosgrove was in "greatly improved condition" and "without doubt, he will be able to reach Olympia by January 11" ("Cosgrove Expects ..."), in time for his scheduled inauguration.

Mr. Cosgrove Goes to Olympia

He didn't make it. Bad weather in Olympia caused him to put off his departure, and for a time it was believed he would not return until spring. Contradictory rumors flew over what would happen next, until Cosgrove departed for Washington in a private railcar later in the month. He arrived in Olympia on Wednesday, January 27, 1909, to a lucky break in the weather: The sun was shining brightly, and the temperature was in the 40s. There had been a plan to administer the oath in his railcar, but Cosgrove insisted on traveling to the capitol for the swearing in. He was picked up by a retinue of officials and taken by automobile (likely the first governor in the state to travel to his inauguration by car instead of carriage) to the capitol, arriving about 3 p.m.

A packed house was waiting for him inside the assembly room of the House of Representatives, and people were shocked by what they saw. Cosgrove had lost 85 pounds during his illness (due in part to a diet of nothing but malted milk and hot water), and the previously sturdy man seemed to have shrunk to almost nothing. He walked down the aisle to a thunderous round of applause, bowing and smiling at the audience. He was supported on either side by two of the tallest men in the Senate, Alex Polson and John Stevenson, and they helped Cosgrove out of his overcoat when he reached the podium. As the audience took a closer look at the new governor, many of them – both men and women – broke into tears.

A brief, minute-long speech had been prepared for Cosgrove by his son Howard and his political advisor Eugene Lorton (1869-1949), who also was editor of the Walla Walla Bulletin. Cosgrove instead delivered his own 10-minute address to a silent, rapt audience. He began the address in a weak voice, but as he continued both the audience and the press noticed that he seemed to gain strength. He thanked the crowd for its support and admitted that he'd nearly died: "A few weeks ago I was led down into the valley of the shadow of death and I was allowed to peep almost on to the other side, but for some reason or other I have been called back and I am here with you again" ("Gov. Cosgrove's Life ...").

He asked that the legislature pass a local option law, which would allow voters in any town to vote whether to license saloons in their community, and it did before the session ended that year. He asked for a constitutional amendment to give the state railroad commission additional power to control rates. And he asked that the new direct primary law be strengthened, and argued that there should be two candidates for each judicial position on the ballot instead of only one. He concluded by asking for a joint resolution granting him a leave of absence pending his recuperation, and then took the oath of office from Washington Supreme Court Justice Frank Rudkin (1864-1931).

Cosgrove remained in Olympia for the next two days, conducting some business from his private railcar. He first act was to appoint Howard Cosgrove his private secretary, and he made several other appointments. He met with Lieutenant Governor Marion Hay (1865-1933) on the afternoon of the 28th to discuss further appointments that he wanted Hay to make after he returned to California, since Hay would become acting governor as soon as Cosgrove left the state. (Hay was prepared; he had already moved into the governor's office.) The new governor had such a good time that his son and others guarding the railcar relaxed their vigil and allowed many of his old friends to drop in and visit.

Final Days

When Cosgrove arrived back in Paso Robles on February 2, he was reported to be tired and weak. Three weeks later he was reported to be steadily improving, and as February turned to March, the news reports from California remained positive. He was deliberately kept in the dark by his family and others about what was happening in Olympia (the legislative session that year was particularly acrimonious, in large part because of the local option issue), and his doctors and family discouraged him from asking questions. He amused himself by telling visitors stories about old-time Washington politics.

By late March, there were consistent reports coming out of Paso Robles that Cosgrove would return to Olympia in May or June. However, the governor's condition suddenly worsened. He remained conscious and cheerful, and though his doctors were concerned, they did not believe death was imminent. His wife was with him in the predawn hours of Sunday, March 28, when, without warning, he had a heart attack. "Death came so suddenly that there was no chance for leave-taking words between husband and wife," reported the Seattle-Post Intelligencer. "Gov. Cosgrove lapsed into unconsciousness and the flame of life flickered out almost instantly" ("Death Is Due ...").

Cosgrove became known as "Washington's One-Day Governor" based on his brief inaugural address in Olympia, even though he carried out some executive duties for three days while he was in the capital, and even though he was, at least technically, governor for two months. Nevertheless, the story of his short tenure has largely overshadowed the story of the man himself, and of how he achieved his long-sought goal through sheer tenacity.