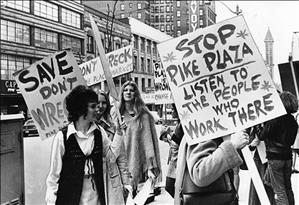

On November 2, 1971, Seattle voters approved Initiative One, creating a seven-acre historical district in the heart of the city and saving the 64-year-old Pike Place Market from demolition. In 1981, the 10-year anniversary of the vote, The Weekly's Joyce Skaggs Brewster took a behind-the-scenes look at the 13-year battle to save the market, focusing on the movers and shakers – Victor Steinbrueck and many others – who made it happen. "The David-and-Goliath version of the struggle that has entered the city's mythology is only partly true," Brewster writes. "Profit and power were certainly issues in the market battles, but equally at issue were two conflicting visions, not only of the market itself but of civic good." Published in The Weekly in September 1981, Brewster's story is reprinted here with the author's permission. In Part 1, battle lines are drawn between preservationists and developers and the fight begins.

Cutthroat Tactics

From the first, the city took the threat of the initiative campaign seriously. As the signature drive kicked off, Mayor Uhlman proposed his own ordinance to preserve "the historic character" of the market (that, is, Pike Plaza's 1.7-acre market), a proposal approved at a packed hearing of the City Council Planning Committee on June 10, 1971, when the committee also voted to recommend authorizing Uhlman to accept $10.6 million in HUD funds. Throughout the summer and fall, both Jim Braman and City Councilwoman Phyllis Lamphere were working on compromise proposals to woo the voters away from the Initiative. (Mrs. Lamphere, who as Chairman of the council's Planning Committee had presided over most of the Pike Plaza hearings, was a particular object of the Friends' wrath. They felt she had betrayed her progressive principles, and their early support of her, by lining up with the urban-renewal team at the critical moments.)

No doubt the city was uneasy at the national attention the battle was beginning to attract. The June issue of Gourmet magazine featured a rhapsodic article about the market, and The New York Times of June 6 carried one of a series of Ada Louise Huxtable articles on historic preservation, this one focused on the market. "The old arguments," she wrote, "of obsolete plants and structural and fire hazards that worked so well for the bulldozer and brought 12-percent returns for a few shrewd and aggressive investors don't convince people anymore. Too many have learned too much from watching the wreckers, and results.” An earlier Newsweek story was also mainly sympathetic to the preservationists. Newsweek quoted Uhlman as saying, "I never promised we would preserve every piece of lettuce. I only said we would try to retain the flavor.” Emmett Watson, himself a long-time Friend, reported Steinbrueck's riposte: "Last time the mayor came down to the market we gave him lettuce, crabs, and fruit. Next time he comes we'll give him a bag of flavor."

Having risen phoenix-like from the ashes of so many defeats, the Friends were now paid the ultimate compliment: their opponents adopted their language and their tactics. The Department of Community Development (DCD), urged on by the mayor, prepared a sheaf of "informational materials" about the urban-renewal plan, which stressed that the whole raison d'etre of the Pike Plaza Plan was to save the market. One large two-color brochure provided atmospheric photos and sketches of the market amid assurances about "preservation," "sensitive staging," "new homes" for market residents, "minimum possible change in appearance," and so on. Conspicuously absent was any visual portrayal of Scheme 23, any reference to tearing anything down, or any indication that urban renewal's market was only a fraction of the market other people wanted to save. DCD also sent on the road a folksy, ain't-it-grand slide show; one typical passage warns that without urban-renewal funds (available, the text strongly implies, only by way of Scheme 23), market rents would have to rise – "It might result in a different kind of tenant in the market, and we wouldn't want to see that happen.”

The city, however, was legally constrained from outright electioneering against the initiative, and so the Central Association began preparing its own imitation-Friends campaign. Early in the summer (according to a KOMO-TV documentary by Patrick Douglas, later the basis of a Harper's magazine article), James Walsh of the Bon Marche met with advertising executive Irving Stimpson to plot anti-initiative strategy. Stimpson then hired Mike MacEwan, a 27-year-old public relations consultant, and the two had further meetings with downtown businessmen. The plan that emerged was to open headquarters in the market and recruit market property owners and merchants to form a "citizens' committee" with no visible ties to the Central Association.

On August 20 the Committee To Save the Market (!) held its first press conference. MacEwan, campaign coordinator, introduced the committee's officers (Reid Lowell, in whose cafe the Friends had been born, and two other market merchants) and backers (Richard Desimone, owner of the main market buildings, and two other market property owners). The committee, said MacEwan, planned a $60,000 fund drive to help defeat the initiative, because its passage would "lead to the destruction of the market by endangering funds needed for its restoration." Steinbrueck immediately charged that the committee was just a front for "the downtown establishment" and Central Park Plaza; MacEwan denied "absolutely" that this was the case. (Another Friends secret agent was at work here, sending Steinbrueck minutes of every Committee To Save the Market meeting.)

Bagdade Builds Alliance

MacEwan began meeting weekly with DCD staff to coordinate activities and exchange information, an arrangement whose propriety neither party seems to have questioned. He also became a regular feature of the market lecture-debate circuit, speaking three or four times a week all over town. Among MacEwan's adversaries at these meetings, besides Steinbrueck, was a young doctor named Jack Bagdade, who was responsible for the entry into the fray of one last group: the Alliance for a Living Market.

Formation of the Alliance was announced on September 7, but its origins, like the Committee's, went back a few months. Bagdade, a regular marketgoer since coming.to Seattle for a medical residency in 1965, had joined the Friends' picket lines back in the spring. He began going to meetings and paid dues, but came to believe that the movement needed a broader base and different "image" than that of the rather shaggy, artsy, or academic "disciples of Victor Steinbrueck." Once the initiative process began, Bagdade was convinced that the Friends' political naivete, lack of organizational skills, and "blind optimism" would spell defeat for the cause unless other forces were brought into play.

An energetic and striking figure, Bagdade began putting together his Alliance. At the suggestion of Gerry Grinstein (recently returned from his years in Washington as Senator Magnuson's chief aide), he recruited a couple of high-powered graduate students as political operatives (one was Al Pierce, who had worked for the Kennedy machine in Massachusetts). A speech at a market rally led Bagdade to Frank Miller, a member of the cooperative that ran the Soup and Salad restaurant on the market's lower level. Miller, who was independently organizing a Merchant's Association as a forum for discussing the market's future, was important in giving the Alliance a base operation in the market and contact with the merchants. A couple of young attorneys, Susan French and Tim Manring, rounded out the steering committee.

Bagdade had spotted Manring on a TV newscast of the July 28 City Council hearing about the initiative petition, where Manring testified as a representative of CHECC (Choose An Effective City Council). This group of young political activists was then headed by John Hempelmann, very much a rising star and colleague of Manring's in the Perkins law firm. Although Manring had only been in town since the previous December, Hempelmann had already got him involved in CHECC and Manring in turn had got CHECC involve the market, forming a committee and doing the kind of thoughtful, meticulous research that was his forte. The result was Manring's City Council testimony, a carefully argued case against the economics of the urban-renewal plan.

The Friends had raised some of the same issues, but Bagdade and Manring felt that the economic argument had to be made more forcefully, and this became the focus of the news conference announcing the Alliance (Manring and Jack Levy of City Fish, co-chairmen). Contrasting the current depression with the city's own 1967 economic study, which had cautioned that the boom conditions then prevailing were "of vital importance to the Pike Plaza Project," Manring pointed out that apartment vacancy rates were up from 1967's 0.6 percent to a current 13.2 percent and that Seattle's present luxury hotels were having a hard time keeping their rooms filled. Consequently, "both demand and available financing" for two key components of Scheme 23 "are severely limited." Resulting delays in construction could turn Seattle into another Baltimore, where 35 acres still lay vacant nine years after federally funded demolition for urban renewal. During the delay no new jobs would be created, but hundreds of people currently working in the market area could be expected to lose their jobs, as the network of small businesses there endured the uncertain fate of relocation. (Small Business Administration figures showed that 31 percent of dislocated businesses failed, 50 percent if they were food related.) Finally, in the "tiny" rehabilitated core market itself, the city's own study predicted a tripling of rents and the return of only a third of the current tenants – the rest to be replaced by "chic Ghirardelli Square-type" enterprises. In short, Scheme 23 would be "an economic disaster," and the Friends' initiative was the only way to stop it.

Uneasy Partners

Manring was careful to pay tribute to the Friends in his press release, and he now says that he (unlike Bagdade) never saw the Alliance as a criticism of the Friends but only as a different and complementary kind of organization. "Victor was more like Saul Alinsky; we were more concerned with putting together a coalition that could work with the city later if we won."

Nevertheless, the Friends did not exactly welcome their new allies with open arms. Steinbrueck, who was in London for a month when the Alliance went public, still believes that the group did little but add to the confusion that "was our most serious problem," though he acknowledges that there were "good people" working in it. For its part, the Alliance seems to have recognized only rather late in the game that, in the public mind, Steinbrueck was the crucial symbol of the "real" market-savers. A handsome silk-screen poster that said only "Vote Yes – Market" had to be reprinted with Friends of the Market and Alliance endorsements added on, because people wouldn't display the poster until Steinbrueck's imprimatur told them what it really meant.

Still, the Friends and the Alliance did manage to work together, thanks largely to the efforts of Jerry Thonn. An affable, low-key conciliator whom many regard as the unsung (or at least undersung) hero of the later stages of market-saving, Thonn held Saturday morning meetings of the two groups in his living room. There the delicate issues of who did what and with which funds were plotted out.

By this time a last, indispensable member of the Alliance team, campaign coordinator Harriet Sherburne, was hard at work. Recently returned to Seattle from political work in Chicago, Sherburne had run into old acquaintance Tim Manring late in the summer and been instantly recruited to replace Al Pierce, who had to return to school. The Friends had expected to get the initiative on the September primary ballot, but the city council delayed taking action until it was too late – a ploy, according to the Friends, that allowed the urban-renewal forces more time to organize against the initiative. Sherburne found that Pierce had done little but antagonize a few important people, that the Friends were in very low gear because of Steinbrueck's absence, and that money was short, but she plunged in.

The first step was to get out a mailing to all the signers of the initiative petition. Jean Falls contributed $1,000 and carloads of volunteers from Bush School to this effort; after endless nights of addressing envelopes and piling them up in hallways, as well as a last-minute printing fiasco, the letters went out. Although the mailing didn't really make money, it brought in "heartwarming" letters of support and a cadre of volunteers.

Sherburne also worked on putting together an advertising and media campaign, enlisting volunteer services wherever she could. One tricky moment, she recalls, came when Steinbrueck (whose market sketches and posters were not universally admired in the Alliance) wanted to do the art work for the ads. The ad agency searched through the Sketchbook and managed to find a single little shopping-bag lady, seen from the rear, whose magnified image satisfied everybody and became an effective emblem for the campaign. Another potential crisis arose late in October, when Sherburne desperately needed funds for a last TV blitz and the only resources available (aside from Jack Bagdade's mortgage payment, which, he contributed) were 30 lithographs that Mark Tobey had sent to the Friends. Only one of the prints sold at a Highlands party held for that purpose, but the Friends were persuaded to use the rest as collateral for a bank loan, and Sherburne got her TV ads.

While Sherburne was managing mechanics, the strategists were also busy. On September 21 the Alliance announced the results of its poll of market merchants: of 82 merchants who responded to the questionnaire (160 received them), only 11 percent favored Scheme 23 when its details were spelled out — although 41 percent replied "yes" to the more generalized question, "Are you in favor of the urban renewal project?" Mike MacEwan immediately denied that the poll proved anything, since by his count there were 230 merchants in the market. MacEwan's Committee To Save the Market also replied with an ad headed "Pike Place Market Merchants Ask Your Support" and listing about 35 merchants as endorsers, including such stalwarts as Pete DeLaurenti and Sol Amon. "We've been analyzed, scrutinized, and idolized by every hippie, do-gooder, and dilettante who has needed a special project to earn a market merit badge," read the ad. "We're sick of it – vote No." Then the Friends issued a flyer listing 79 merchants! (among them several farmers) on their side.

Clearly, the presence of landlord Desimone on the urban-renewal side of the fence put the merchants in a tricky spot. Desimone, according to Frank Miller, was a strong daily presence in the market, a kind of benevolent feudal lord who took seriously every market transaction and the quality of every head of lettuce. Both personal allegiance and prudent self-interest undoubtedly influenced some merchants to line up with Desimone or to sit out the battle. There also seems to have been deeper and widespread concern among merchants about the "winos-bums-and-hippies" problem than the Friends ever wanted to acknowledge. Still, except for a contingent of the more substantial merchants who genuinely believed that urban renewal offered their businesses a better chance to thrive, Miller thinks the majority of market tenants supported the initiative. The Merchants' Association itself never took an official stand – "We knew we had to go on living there after it was all over," says Miller.

On another front, the city's efforts to come up with a compromise were now in high gear. Both Phyllis Lamphere (running for reelection against Bill Harrington, a candidate backed by the Friends) and Jim Braman were behind a set of Scheme 23 amendments proposed to the City Council by DCD late in September. The changes: expand the zone reserved for market uses from 1.7 to 3.5 acres, which would include among other things the Sanitary Market, the Triangle building, and City Fish; prohibit demolition in the project until the City Council should have approved redevelopment proposals in hand; eliminate the double-deck distributor road; and make provision for more low-income housing, for relocation of tenants near the market, and for "reasonable rent schedules" in rehabilitated buildings.

For the Friends and the Alliance, these proposed changes were too little, too late, and too untrustworthy – "clearly a political maneuver designed to mislead the voter," the Alliance charged. The city council then put off even acting on the amendments until it could also consider a review of the economics of the urban-renewal plan, recently commissioned from the same consultant that had done the original 1967 study. In mid-October the consultant presented his preliminary conclusions: the hotel "might" be feasible, in another eight years or so, there would be no demand for first-class office space until 1975, and the 1,400 apartment units of Scheme 23 should be scaled down by half. While the Friends and Alliance were "heartened" by this report ("The experts have finally caught up," said Steinbrueck), the City Council Planning Committee took it as a sign that still further hearings were needed on the plan; rather than adopting DCD's amendments it therefore sent them off to the law department for drafting into an ordinance for public debate – a step that could not be completed before the election.

Hence the city's "compromise," whatever its merits, was only a promise on election day. But then so was the assurance by the Friends and the Alliance that urban-renewal funds would still be available if the initiative passed. By now both sides were agreed that these federal monies were essential to whatever form of market-saving each espoused, and the most damaging charge of the anti-initiative forces, constantly repeated, was that the initiative would in fact "doom" the market by delaying or eliminating altogether the funds HUD had already promised for the city's plan. The initiative, the argument ran, would in effect create a whole new plan, subject to all the funding delays and uncertainties that Scheme 23 had at last successfully negotiated, and would perhaps, by all its restrictions, so discourage private investment that HUD would find it unfeasible. To this the Friends and Alliance always replied that they were not against urban renewal but only wanted to channel the funds into a more sympathetic treatment of the market area, and that since HUD had never withdrawn funds from an approved project there was no reason to expect that now.

In the last weeks before the election everybody was trading quotations from four shadowy letters written by HUD's regional director in Seattle and two from an assistant secretary in Washington. None, unfortunately, made a definitive commitment one way or the other. But the Alliance cited one letter's expectation that funding would continue after passage of the initiative "to the extent that the project remains viable" and another letter's promise that HUD "is deeply committed to historic preservation." And on October 27 Braman, announcing that his worst fears had been confirmed, offered his HUD quotation: passage of the initiative would "remove, the project status from one of certainty based on known plans and agreements to one of uncertainty due to a multitude of new factors." Concluded Braman, "This is clearly a risk that the people of Seattle cannot afford." (Braman now confesses he didn't actually believe the risk was all that great, though he had a "real concern." Harriet Sherburne, for her part, admits that there were a lot of crossed fingers behind the Alliance's confident predictions. So much for campaign rhetoric.)

Voters who really wanted to save the market thus had to choose on November 2 between two unverifiable promises: 1) that the city would have the will, muscle, and understanding to preserve not merely the name but also the essence of the market; 2) that the forces behind the initiative would have the practical resources to carry out their plans, The potential disasters on either side were quite different, but either would suffice to finish off the market. Among the several newspaper columnists who said, in effect, that they would vote "yes" and pray was Don Carter of the P-I: "Others should place their votes where they place their trust – because that's the only real issue in this election."

If trust was the issue, the Committee To Save the Market was in trouble – and, by association, the whole effort to defeat the initiative. Two rocks on which it was foundering were the state's new law requiring disclosure of campaign finances and a KOMO-TV documentary – appositely titled "Who Will Save the Market?" – by Patrick Douglas.

In mid-September CHECC's John Hempelmann had called on all sides "to make at least three campaign finance reports during this month and next," since the legal deadline for the reports, October 31, would be "too late to adequately inform voters casting ballots on November 2." (The Alliance was annoyed that CHECC, on whose early endorsement they had counted, did not in fact come out for the initiative until late in October; but raising the financial-disclosure issue turned out to be more significant.) The Friends and the Alliance immediately complied with the request. Mike MacEwan declined, saying that his Committee would observe the legal deadline. "One can only assume the Committee has something to hide," prodded Hempelmann.

Another exchange followed in mid-October, with CHECC announcing that the Friends and Alliance between them had raised about $7,200 and wondering aloud why the Committee was afraid to make a similar disclosure. At this point. MacEwan conferred with his backers, who apparently decided that valor was the better part of discretion, and on October 15 the Committee released its list of contributors. The largest single contribution was $3,000 from Desimone's Pike Place Public Markets, Inc., but the rest of the list ($23,315 total) read like a roll call of the downtown business establishment: $2,500 from SeaFirst $1,700 from Washington International Hotels, $1,700 from Safeco, $1,500 each from Central Park Plaza and Frederick & Nelson, $1,000 from Doces, and so on.

MacEwan still insists that there was no "conscious policy of confusion" involved in setting up a committee of market merchants "to save the market" and financing the operation with money from corporations whose main interest was saving Scheme 23. At any rate, the Committee's credibility suffered a blow when its long-denied financial ties with downtown were revealed. Douglas's KOMO documentary on October 27 completed the damage, showing that the Committee was indeed the brainchild of the Central Association and catching MacEwan in some embarrassing inconsistencies.

Although MacEwan ranked high in the demonology of the market-savers, both Bagdade and Manring today concede that he was "given a bad rap." MacEwan points out that he was hired on as a "legman" for the campaign but ended up as a spokesman "because nobody else would do it," the eminences grises not wishing to reveal themselves. A "naive rookie" thrown to the lions (Steinbrueck, Hempelmann, Pat Douglas, et al.), says MacEwan, he came out of the campaign with a permanent conviction that "politics is a dirty rotten business."

MacEwan also contends that "the business community, the people who literally made this city, just got crucified" in the campaign; once the opposition had "sidetracked" the campaign with the "concocted issue" of the Committee's finances and origins, the "real issues" raised by the Committee never got a fair hearing. Would the business community have got a fairer hearing if it had been more open about its position? MacEwan ponders this question as if it had never occurred to him, but then answers no; the political climate was such that overt campaigning by business interests was out of the question.

This picture of the business community as the underdog of the campaign provokes astonishment and incredulity among pro-initiative veterans. Certainly he has a one-sided version of who was playing fair and who was not, but MacEwan puts his finger on a truth that all the money, power, and political connections of the Central Association tend to obscure: the cozy, paternalistic team of downtown business, major editorialists, and City Hall that had seemed so natural back in 1958 was no longer selling very well in 1971. The 1960s, Vietnam, and a new generation had intervened. Reading the list of Initiative endorsements is like looking into the political future of Seattle: City Council candidates John Miller and Bruce Chapman, CHECC, numerous community councils, the Young Lawyers Section of the Bar Association, the Washington Environmental Council, Young Democrats and Young Republicans. The initiative campaign was the last hurrah of an older version of civic authority, which has not recovered its stride or self-confidence since.

Not surprisingly, everyone on the winning side remembers the campaign as a grand affair – "the most exciting time of my life," says Bagdade typically ... The pace grew more and more hectic as election day approached. Both sides were giving tours of the market and issuing press releases almost daily; writers and experts from everywhere came to town to pronounce on the fray; the city dramatized its case by closing several market hotels for code violations; the Friends and Alliance held a dizzying round of fundraising parties and benefits (Tim Hill won the City Council candidates' tricycle race); Tim Manring put together his own slide show (featuring markets in Afghanistan and Indonesia) to combat the city's. "Utter confusion reigns," said a Times editorial.

"It looked like a toss-up till the very end," recalls Jerry Thonn, "but during the last week, when reports started coming in from the doorbelling, we were beginning to feel pretty good." By 10 on election night, when the dimensions of the victory became clear, they were feeling very good indeed. The celebration party circulated between the Brasserie Pittsbourg and the Allied Arts office on South Main. "I feel better about Seattle," said Victor Steinbrueck. "This is a people's victory." At about 10:30 Jim Braman appeared at the party "with ketchup smeared over his wrists," as Emmett Watson reported, "and a good-sport smile on his face." And the front page of the next day's Times showed Steinbrueck and Jack Levy at a market stall, under the headline "A Real Place In a Phony Time."

The market was not really saved, of course, on election day. After the jubilation, John Cline (now Executive Director of the PDA) remembers a sense of panic: "How do we do it?" But somehow the process went forward without any of the possible catastrophes. Uhlman and Braman, far from displaying sour-grapes hostility, spotted the new political order at once, behaved handsomely, and went to work to translate the will of the electorate into reality. The HUD funds did not evaporate but in fact multiplied astonishingly in the years to come, thanks partly to the Magnuson machine and partly to the project's track record of good management under James Mason and Harriet Sherburne. The difficult process of institutionalizing the Friends' vision of the market in a revised urban renewal plan was finally, painstakingly completed (though Steinbrueck never would approve the plan). The young organizers of the Alliance followed through to create, in the Preservation and Development Authority, the sort of nonprofit public management agency that had long been considered the market's best hope of survival. And a number of changes in "lifestyle" have worked to the economic advantage of a central urban marketplace: "A minor miracle," says Ibsen Nelsen of the way it’s all worked out. The market had a public mandate, the federal government had money, and the urbanites were coming to town -- and it all happened at once.

Jim Braman cheerfully admits that the market today ls much better than it would have been if the initiative failed (he visits it every Saturday morning). Architect Paul Kirk granting that Scheme 23 "did kind of cut a hole in the fabric of that part of town,” also now prefers the initiative’s market to his own. John Gilmore, head of the Downtown Development Association (successor to the Central Association), calls the rehabilitated market "a tremendous part of downtown."

Even Victor Steinbrueck, always the market's last angry man, is more or less reconciled to the changes that have inevitably attended the practical work of market-saving. He is uneasy (as are others) about the loss of much of the old residential community, the increasing middle-classness of the market scene, and what he takes to be the fancier architectural flourishes of some of the restorations. "It's not exactly what I'd dreamed. But" – he adds immediately – "when I think what it might have been if the initiative had failed ..." And Steinbrueck clearly takes deep satisfaction in the role he is universally accorded: that of the one indispensable man in the long fight against the "black ball of destruction." "Compromise is not Victor's bag," says Jerry Thonn, in one of the more tempered assessments of this side of Steinbrueck's character, "but his anger and stubbornness carried us a long way. it couldn't have been done by calm, rational, compromising characters like me."

The market victory, which seemed like the dawn of a new political era at the time, has turned out to be somewhat less than that, however. True, the market itself was saved and turned into one of the most successful urban renewal/preservationist projects in the world – the subject of envy and study by planners throughout North America. But the annus mirabilis of 1971 turned out to be short-lived, another example of Seattle's glory and bane: reform by spurts.

The papered-over splits between the pragmatic Young Turks symbolized by the Alliance and the intransigent romantics epitomized by the Friends only grew worse in the years to come. Consequently, the new wave of reform turned into a force mostly designed to block things — I-90, the Bay Freeway, waterfront development — but never gained the coherence to create many projects. The old Order was demolished, but then the New Order never grew up. By the mayor's race of 1977, the progeny of the Alliance had gathered around Paul Schell and the offspring of the Friends had rallied to Charley Royer: the two sides never healed the splits from that race. The battle to save the market was won, but the wider war to transform the city resulted in a negotiated stalemate.

The market has nourished Seattle politics in its many waves of enthusiasm: populist beginnings, social pretensions in her youth, scruffy picturesqueness in the bad times, and the present tide of gentrification. The broad arms of her arcades embrace all corners, all suitors. In saving the market yet one more time, her admirers glimpsed the possibilities of Seattle politics at its most exhilarating and enjoyable.

The old emotions of common cause and noble purpose are being revived in the numerous meetings held this fall by old friends and old antagonists who have gathered for a few more rounds of back-patting and fellow-feeling. There will be parties and street music and potlatches, and a show of Tobey's drawings and a dedication of a new park designed by Steinbrueck. In short, the reunion of that most promising set of alumni in decades, the Class of '71.