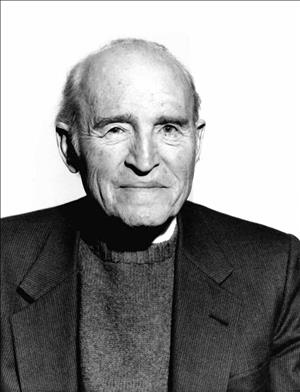

Among his many achievements as a civic activist, Seattle attorney Jim Ellis (1921-2019) led the campaign to clean up Lake Washington, pushed for development of the Washington State Convention Center, and founded the Mountains to Sound Greeway Trust. In this excerpt from his memoirs, Ellis writes about Washington State Supreme Court Justice Charles Horowitz (1905-1989), who in 1949 was one of six partners managing the Preston, Thorgrimson & Horowitz law firm when Ellis was hired. Horowitz would be influential in shaping Ellis's start in law.

Brilliant Legal Mind

[Author's note by Jim Ellis: I am indebted to a carefully written feature article by Chet Skreen that appeared in the December 14, 1980, issue of The Seattle Times for much of the early biographical information about Charles Horowitz.]

Charles Horowitz was born January 5, 1905, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Harry and Fanny (Mirkin) Horowitz. He was the oldest of five children. His parents had immigrated from Czarist Russia just a year before Charlie had been born. He spent his early childhood in the tenement district of Manhattan’s lower eastside, where his father worked as a tailor. It was an era of child labor, sweat shops, and juvenile warfare. Each block had a club, Horowitz recalled, and if you didn’t belong to the right gang, you didn’t walk on that block. One day he was cut with a broken glass because he had strayed beyond his block.

The Horowitz family moved to Seattle when he was 8. Charlie recalled seeing a Dandelion for the first time, and thinking it was the most beautiful flower in the world.

In Seattle as a school child, young Horowitz worked in a downtown theatre, sold newspapers on East Madison Street, and had a magazine route in the downtown district where he sold the Saturday Evening Post for five cents. In summer months he worked downtown in food and vegetable stands. His earnings helped pay for his education at the University of Washington. After graduating from the UW, where he received an AB degree Magna Cum Laude in 1925, Charlie received his law degree Summa Cum Laude. He was the editor of the UW Law Review 1925-27; and had been elected to Phi Beta Kappa in 1925 and to the Order of the Coif in 1927. (The Order of the Coif is the law school equivalent of Phi Beta Kappa for the upper 10 percent of the graduating class in Law School. I missed being awarded the Order of the Coif, because of a "C" grade received in my last year in credit transactions. Each year a chapter may elect one honorary member and I was elected in 1948, by the University of Washington Law School.)

In his final year at the university, he was awarded a three-year Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University in England with an annual stipend of 400 pounds.

Charlie finished his three-year law courses at Oxford in just two years in 1929, receiving a BA in jurisprudence with first class honors. He returned to the Seattle area and joined the Preston firm after having first been turned down for a job by Harold Preston because there was not an opening at the time. Charlie asked for permission to work for nothing at the office and suggested he could set up his desk in the library if Harold Preston would hire him. After a few weeks, Charlie demonstrated that he was just what the firm needed, and Harold Preston put him on the payroll.

Charlie proceeded to develop into one of the best lawyers in the city, recognized for his appellate advocacy and for outstanding service to the legal community. Eventually, he was elected president of the Seattle Bar Association and among his clients was United States Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, perhaps the most liberal high court jurist of the century. Charlie won high praise from unlikely sources such as James Kilpatrick, the curmudgeonly conservative columnist, who once referred to him as "a distinguished jurist of the Pacific Northwest" in his syndicated column.

He was admitted to the Washington State Bar in 1927 and served as a lecturer in law at the University of Washington Law School, 1932–33, 1939, and 1945. Charlie was a life member of the American Law Institute and was elected president of the Seattle Bar Association in 1957–58.

Among my first jobs as an apprentice was to serve legal papers which needed proof of the time of receipt. Charles Horowitz was a prolific producer of questions of fact to be answered under oath by anyone asserting a claim in Court against his client. He usually dictated these lengthy "interrogatories" to his secretary early in the morning and they were notoriously detailed. One afternoon I served upon an unsuspecting lawyer a thick set of Charlie’s questions. The poor man actually began to shake as he angrily thumbed through this pile of paper, saying, "How many people in your big office worked on these?" I answered that Charlie did this by himself. As I closed the door behind me, I heard him mutter, "No man could do this. Horowitz isn’t human, he’s a machine!"

Charlie had always hoped to culminate his legal career by serving as a justice of the State Supreme Court. In 1968, he was appointed by Governor Evans to be a justice on the newly created Court of Appeals for the State of Washington and was re-elected in 1970 and 1972.

The Horowitz legal career reached his goal in 1974, when he ran for an open seat on the State Supreme Court and was elected statewide by more than 121,000 votes! Charlie wrote 270 opinions during the six years he served. He retired from the high court in 1980 because of statutory age limitation and returned to the Preston firm in Seattle, where he became a senior statesman in the office.