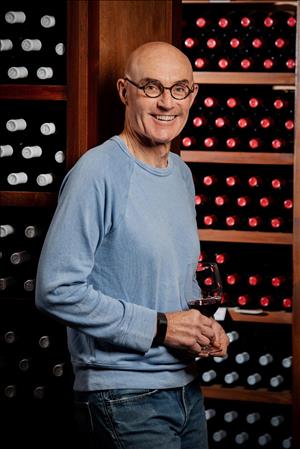

Rick Small (b. 1947) is a pioneer Walla Walla Valley winemaker whose Woodward Canyon Winery and Estate Vineyard helped usher in a Walla Walla wine boom. He was raised on his family’s wheat farm north of Lowden, Washington, and earned a degree in agricultural mechanics. Yet a trip to Europe after graduation spawned a love of wine. He realized that he would rather raise grapes than wheat and jumped at the chance to plant some vines on the family farm. In 1981, he and his wife Darcey Fugman-Small bonded the Woodward Canyon Winery in Lowden, only the second winery in the Walla Walla area. His wines immediately won a dizzying array of awards. In 1992, a national wine magazine named him Winemaker of the Year. After four decades, the winery is still making award-winning wines and Small is widely recognized as one of the founding fathers of the Walla Walla wine industry.

Agricultural Roots

Richard Lewis (Rick) Small was born in Walla Walla at St. Mary Hospital on February 8, 1947. His parents, Ray Small Jr. and Margery Jean Small, nee Wolfe, lived on a farm just north of Lowden in Woodward Canyon on Nelms Road. Both parents descended from families with deep agricultural roots in the Walla Walla Valley. His mother’s family had been farming in the area for five generations; his father’s family, for three generations. Their Woodward Canyon farm was a wheat-and-cattle operation. When Rick was growing up, growing wine grapes was not considered an option on their farm – or on any area farm. Some Walla Walla pioneers in the 1800s had grown some wine grapes, but those vineyards had been gone for decades.

Rick and his three brothers all worked on the farm while growing up. "I started driving trucks when I was like 12 or something," said Small. "I would help move the trucks around on the hill and stay in the field – I didn’t do anything illegal. But by the time I got to be 15 ... I started driving a combine" (Kershner interview). It wasn’t all work for the Small brothers. "We just absolutely had a blast," recalled Small. "We had wagons and bikes, and so we would customize stuff and build them and ... we'd sled down the hills. And you'd crash your bike on the street or on the road. It wasn't a street. In fact, it was a gravel road for a long time" (Kershner interview).

He attended elementary school at the Lowden Schoolhouse, which would later become famous as the home of the L’Ecole N° 41 Winery. "It was still a two-room schoolhouse," said Small. "And there was a fabulous little downstairs cafeteria with bathrooms down there and a little stage. And so all of my brothers, my cousins, and a lot of my best friends, we all went to school there" (Kershner interview). He would go on to Garrison Junior High and Walla Walla High School. Wine never played a part in his family’s life – nor did it play a part in the life of most Walla Walla area families in the 1950s and 1960s. "I don’t recall seeing anyone, ever, drink wine," said Small (Kershner interview).

In high school, he realized that he loved drafting, mechanical drawing, and science. Upon graduation, he told his father that he wanted to go to the University of Washington and study architecture. "I loved growing things – still do – but I really kind of wanted to pursue architecture," said Small. "... I kind of got talked out of that by my dad" (Kershner interview). He ended up going to Washington State University and studying agriculture. He got a Bachelor of Science degree in agricultural mechanization, a field that would someday prove useful in a career that he had yet to envision: growing vines, harvesting grapes, and making wine.

Lessons in Wine

Small remembers drinking wine in college, but it was wine such as Boone’s Farm, "just concocted fruit juice with some other alcohol pumped into it." This had the opposite effect of spurring an interest in wine. "It was disgusting," he said (Kershner interview). Yet soon he would learn what he had been missing. He and two friends decided to celebrate their graduation from college in 1969 by traveling through Europe for two months. They traveled through France, Germany, Austria, and Italy and discovered that wine was an integral and delicious part of the culture. He remembers meeting people from all of those countries and becoming friends over wine. "I guess the whole thing about wine for me, it’s just civilized," he said. "It’s a way to get into conversation with people, brilliant conversations over almost anything. And I just absolutely loved it" (Kershner interview).

He especially recalls drinking German white wines and falling in love with them. When he came home, he went back to the family farm business, but he now had another passion – wine – to go along with his continuing interest in architecture. He applied to the Washington State University School of Architecture and was accepted. But his father was never sold on the idea of Rick leaving Walla Walla to pursue a career in architecture. He wanted Rick to stay with the family business. So when Rick asked if he could plant a trial vineyard, his father offered Rick one strip of land for grapes. It was shallow basalt land, unsuitable for wheat.

In the mid-1970s, Rick’s interest in wine had only deepened. He had already helped his friend and fellow Army Reservist Gary Figgins plant some Cabernet Sauvignon vines on a patch of Walla Walla Valley ground belonging to Figgins’s uncle. At the time, neither Small nor Figgins was certain that Walla Walla was even suited for fine wine grapes, but they were burning to find out.

Meanwhile, Figgins had further stoked Small’s wine obsession through an unlikely medium: a bottle of Figgins’s homemade strawberry wine. "Back in those days, there was a lot more fruit available than there were wine grapes," said Small. "Gary gave me a bottle of strawberry wine, and I was at my parents’ house for Christmas, and we opened that up. It was really well-made … we all loved it" (Kershner interview). Figgins would later reach near-legendary status with his Leonetti Cellar Cabernets and Merlots, but it was this bottle of strawberry wine that grabbed Small’s imagination like no other bottle before. "It was capturing that fresh Walla Walla strawberry at perfect ripeness and processing that into something that you could drink and have all the pieces and all the parts of the strawberries still there, the acid, the balance, the freshness," said Small. He would later call that bottle of strawberry wine "a game changer" for him (Kershner interview).

Trial and Error

For these reasons, his father’s offer of a vineyard landed on fertile ground with Rick. He accepted the offer – and his life would never be the same. "I think it was my dad’s way of keeping me in agriculture," he said. "I'm really glad he did" (Perdue). From that point on, architecture receded into the background and wine – growing it and making it – became his calling. He continued to work on the farm, and later managed the family’s grain elevator, but wine was now his avocation, soon to grow into his vocation.

That first vineyard attempt had mixed results. He had planted the basalt-strewn strip with Chardonnay vines and watered it from a water truck. He soon discovered that he had planted them too low. The cold air settled in the low spots in the winter, frost-damaging the vines. Also, he discovered that grasshoppers had nothing to eat after the wheat was harvested in late July or August. So the grasshoppers turned their attention to the grapevines. "Oh, it was awful," said Small. "It was terrible. … In some of the early pictures of our vineyard, you’ll see little milk cartons – grapes coming out of the milk cartons" (Kershner interview). Those cartons were his attempt to foil the grasshoppers. Despite these problems, Small was able to harvest enough Chardonnay grapes to make his first homegrown wine. "I got enough to make a gallon," he said with a laugh. "Yeah, it was good. But you have to remember, psychologically, it would have been" (Kershner interview).

Small began to expand the vineyard onto higher and warmer ground. He experimented with different varieties, including Cabernet Sauvignon. He eventually obtained water rights, meaning he no longer had to irrigate the vines by truck. The vineyard grew past its original one-acre size, slowly but surely.

Today, it is the Woodward Canyon Estate Vineyard, the second oldest in the Walla Walla Valley. But back in the late 1970s, Small was still supplementing his homemade wine with grapes from the Yakima and Columbia valleys. He and Figgins had met some friends in the Tri-Cities who had formed a wine-tasting group, some of whom were growing and making their own wines. And then he met one particular friend, Darcey Fugman, who was a land-use planner for Walla Walla County. Soon they started dating and found a shared interest in wine. Together, they became serious about making homemade wine, and became serious in other ways, as well. They married in 1980.

Taking the Plunge

Then, in 1981, Rick Small and Darcey Fugman-Small bonded the Woodward Canyon Winery, the second winery in the Walla Walla Valley after Leonetti Cellar. At the time, nobody knew for certain that Walla Walla could even have a future in fine wine. Yet Rick and Darcey did not hesitate to take the plunge. "The whole concept of failure or not succeeding didn’t even come into my brain," he said. "I guess part of it is I had very little to lose. I had a small little vineyard that I was experimenting on out on our family land, generational family land, and so I just did it" (Kershner interview).

Small also had Figgins as a friend and role model. Figgins had made his first wines in 1978, and they were already winning awards. "By this time, he and I were getting to be really, really good friends and good wine buddies," he said. "And I would go over to his house. While his wife Nancy would work on Friday nights at Martin's jewelry store, I would go over and we'd take six-string and 12-string guitars and open a bottle of wine and play, and just goof around and talk about the wines and tasting, and taste it out and talk about what was in them that we liked and maybe how they did it" (Kershner interview).

Yet the new Woodward Canyon Winery was still, essentially, a side project. Darcey still worked as a land-use planner and Rick was running the family grain elevator on U.S. Highway 12 in Lowden. The first Woodward Canyon Winery building and tasting room was in an old truck-repair shop – almost a shed, really – about 50 yards west of the present Woodward Canyon Winery compound. It was right across the street from the grain elevator, so if he saw someone drive in, he’d shut the grain elevator down and "run across the street and come in the back way, so I could meet somebody coming in" (Kershner interview). He told the Tri-City Herald in 1983 that Woodward Canyon "had no set hours, but someone should be around most of the day during the summer, Monday through Friday" ("Eight Wineries").

The tasting room was informal, but the winemaking was dead serious. Small had learned the technical side of winemaking by writing to the University of California-Davis and ordering all the books the school used in its renowned winemaking curriculum. He also got assistance from the horticulture and food science programs at his alma mater, Washington State University.

In 1982, Small took out an ad in The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, announcing his first releases: a Riesling – made from Walla Walla fruit – and a Cabernet Sauvignon Blanc, which today would be called a rose. They turned out well – in fact, the Riesling won an award at the Enological Society of the Pacific Northwest’s annual contest, then the region’s most prestigious wine competition. The medal was only a bronze and would be surpassed later by dozens of Woodward Canyon awards. Yet Small would later call it the "most important medal I ever won" (Kershner interview). The event was held in what would become Woodward Canyon’s main market, Seattle. It also served notice that Walla Walla was a wine producer.

The next year, 1983, Small added a third wine to his list, a 1981 Chardonnay from Sagemoor Vineyard grapes. It was barrel fermented in expensive French oak and was modeled after a white Burgundy. It would go on to win several regional gold medals. "Those Chardonnays were good and I got a following right away," said Small. "And moreover, because I won that gold medal, I had several different distributors from Seattle immediately call me up" (Kershner interview). Chardonnay would become Woodward Canyon’s best-known white wine, and would remain so through the decades.

Advocating for an AVA

Around this time, Rick and Darcey were working not only on producing wine, but on boosting the status of Washington wine in general and Walla Walla wine in particular. Rick served on the board of the Washington Wine Institute (which later became the Washington Wine Commission) and earlier was the chair of the Walla Walla Winegrowers, the precursor to the Walla Walla Wine Alliance. In 1983, the group decided to pursue a designation for Walla Walla Valley as an American Viticultural Area (AVA). Small said he and Figgins cruised around the valley in his 1967 Chevrolet truck, determining the boundaries. Darcey, still a Walla Walla County planner, wrote the application with the assistance of Becky Hendricks of the original Seven Hills Vineyard and prepared the maps. The AVA was granted in 1984, which allowed the three Walla Walla wineries – L’Ecole N° 41 had recently opened – to be labeled Walla Walla Valley wines, instead of generic Washington wines. "It will help us market our wines," Small told The Spokesman-Review. "But more importantly, it will let consumers know what they are getting" ("Walla Walla Wine Recognized"). It was only the second AVA in Washington, after Yakima Valley.

Woodward Canyon Winery was contributing to the nascent Walla Walla wine industry in an even more fundamental way: by producing quality wines. In 1984, Small released his first Cabernet Sauvignon, a 1981 vintage from Sagemoor grapes. Wine critics immediately compared it favorably to the Leonetti Cellar Cabernets, which had gained a national following. The Woodward Canyon Cabernet was heading the same direction, picking up compliments from critics. "Rick Small is producing some of my very favorite wines in the state," said the Tacoma News-Tribune’s wine critic Corbet Clark in 1986 ("Walla Walla Wineries Producing Treasures"). The 1983 vintage was also picking up prestigious awards, including the Governor’s Trophy for Washington’s best red wine, and a double gold medal from the 1986 San Francisco National Wine Competition. "We’re all pleased that we’re getting gold and double golds for our red wines," said Small at the time. "The region’s first prizes came with white wines, so it’s good to see the recognition for reds, too" (Holden).

The 1984 Cabernet did even better and was named Washington Wine of the Year by the Washington Wine Writers group. With success came a big decision. Should Small take the plunge and go full-time into wine? In 1985, the answer was yes. It was risky, but he felt confident. Woodward Canyon wines had been discovered not just in Washington, but also by wine shops in San Francisco, Southern California, and points beyond. "We got into almost all major markets around the country," said Small. "You could just about make and sell all the wine that you wanted. You just needed space, and the barrels, and the people" (Kershner interview).

From 1986 to 1988, he nearly doubled production from 2,430 cases to 4,654 cases. "By 1988, I was able to hire some help; that was a big deal!" he said (Gregutt). By 1990, Woodward Canyon was being courted by a larger California winery with a possible expansion or buyout in mind. Yet that was not the future Small wanted. He told the Tri-Cities Herald in 1990 that, "I’m having too much fun making wine, to want to sell out" (Woehler). Years later he would say, "I know Darcey and I felt strongly that we wanted to keep it small. And I wanted to plant more grapes up in Woodward Canyon and do a little bit more there" (Kershner interview).

So instead of selling out, they began to slowly expand their operations in the vineyard. Small took out many of those original Chardonnay vines and planted more Chardonnay vines higher up. He also began to experiment with a number of other varietals, including Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, and Grenache. He was still buying most of his Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from other high-end vineyards, including Mercer Ranch (later to become Champoux Vineyard), Sagemoor Vineyard, Charbonneau Vineyards, and the Seven Hills vineyard.

The results continued to be spectacular. In 1990, The Wine Spectator magazine published its 100 Best Wines in the World listing. Small’s 1987 Cabernet Sauvignon came in at No. 10 on the list. It was the first Washington wine to make the Top 10. That achievement was not easy for Small to top, but he soon did. When The Wine Spectator’s April 15, 1992, issue came out, Small was on the cover, named the magazine’s Winemaker of the Year. It was the top award from one of the most influential wine magazines in the nation. He earned this accolade by having three wines in the magazine’s Top 100 list: the 1990 Chardonnay, the 1988 Cabernet Sauvignon, and the 1988 Charbonneau, a blend from the vineyard of the same name. People were calling from all over the country, begging for his wine. One man flew his private plane into Walla Walla to pick up a couple of cases. "I talked to a secretary of an East Coast CEO, who said her boss was very important and he really must have some of my wine," Small told Spokane wine writer Leslie Kelly just after the award ("Up-and-Coming"). That executive, like many others, was out of luck. Most of those award-winning wines sold out immediately.

Reluctant Legend

From this point on, wine writers would routinely use the word "legend" in describing Small. The best-known wine writer in the country, Robert Parker Jr., predicted that both Small and Figgins were destined to become the "superstars of the 1990s" (Kelly, "State Wineries"). This kind of attention – which was now being shared by L’Ecole N° 41 – also helped spawn a dizzying wine boom for the Walla Walla Valley. From those original three, an industry would arise, with more than 130 wineries by 2023. Yet Small was still operating out of a glorified steel shed. "The wine doesn’t know if it’s in an old shed or a $5 million chateau," Small would later say. "We bought the best barrels, and when we started doing better, we began improving the buildings. I know a lot of places that have fancy buildings, but that doesn’t mean you’ll have success" (Perdue).

Woodward Canyon’s building improvement projects started modestly, to say the least. In 1993, he moved the tasting room out of the shed and installed it into an old Quonset hut nearby. Later, along with his friend and neighbor Marty Clubb of L’Ecole N° 41, he purchased a lot that sat between the two wineries and moved the tasting room into the historic F. M. Lowden house. The Woodward Canyon Winery compound would eventually grow to several production buildings, the tasting room, and a modern building called the Reserve House. The entire "downtown" of tiny Lowden was now essentially filled by Woodward Canyon and L’Ecole.

Meanwhile, he found that he loved the most fundamental part of winemaking: growing grapes. In 1999, he said, "I really want to spend the rest of my career growing grapes" ("Big Things"). "You have to have something in agriculture you’re excited about," said Small. "Wheat wasn’t it. Grapes were" (Kershner interview). He grew his Woodward Canyon Estate Vineyard from its original one acre to 41 acres. Many of Woodward Canyon’s finest wines were now labeled estate wines, meaning they were made from grapes from that vineyard. In addition, Small acquired stakes in several other high-end vineyards, including the Champoux Vineyard in the Horse Heaven Hills AVA.

In 2000, Darcey Fugman-Small left her job as County Planning Director and became the general manager of Woodward Canyon. Meanwhile, Rick’s status as a Walla Walla icon continued to grow. In 2003, he told The Seattle Times that he was still amazed and a little chagrined that he was recognized on the streets as a celebrity winemaker. "I’m a farmer, and I still get up early and go to work in the dark," he said. "It's just wine. I mean, get over it" (Mapes).

Transition at Woodward Canyon

In 2003, Small turned over the winemaking duties to Kevin Mott, who became head winemaker. "Handing the winemaking reins to Kevin was difficult," Small said. "But there was no way I could do it all myself" (Perdue).

The accolades kept coming for Woodward Canyon. Its wines made the Top 100 lists dozens of times in magazines such as Wine Enthusiast, The Wine Spectator and Wine & Spirits. In 2014, Wine Press Northwest named Woodward Canyon the Washington Winery of the Year. Small himself received many accolades from his peers, including being named Honorary Vintner at the Annual Auction of Washington Wines, one of the industry’s highest honors.

Around this time, Rick and Darcey began thinking about succession planning. Their two children, Jordan Small and Sager Small, had been sitting on Woodward Canyon’s board of directors since 2010. Jordan had worked at Long Shadows, another renowned Walla Walla area winery, for five years, and then moved into a management position at Woodward Canyon. Sager Small had worked as a cook for many years at top Seattle restaurants, but then decided to attend Walla Walla Community College’s Enology and Viticulture Program, with an eye toward returning to the family business.

In 2017, Small talked about what the future held. "I don’t want the children to be nervous because we are looking over their shoulder," he said. "They need to know they can make mistakes – hopefully not the same ones we made. If you are going to be cautious in business, you’re not going to do well. You have to bring it" (Gregutt).

Woodward Canyon reached a milestone in 2021 when it made its 40th vintage. The succession plan had now been firmly established. As of 2023, Jordan had taken over the reins as general manager from Darcey, and Sager Small had become Woodward Canyon’s vineyard manager.

As Rick and Darcey step away, Woodward Canyon seems destined to remain a family business. "That’s been the children’s decision to make," said Rick. "My wife and I are comfortable. We loved being involved. But I think it’s going to be harder for them than it was for us. I do. I just thought it was easy. I hate to say it that way and I don't mean to be flippant about it ... Sure, I made some mistakes, but they were modest. I was able to correct them" (Kershner interview).

He believes that he was fortunate in having Darcey at his side, "the best partner in this whole thing, ever" (Kershner interview). In fact, he believes that he and Darcey – along with other Washington wine pioneers – essentially got lucky in being present at the launch of a new industry. Not that they had a clue, at the time, that they were launching a Walla Walla wine boom. Years later, he mused that some people "have tried to make this into a story about how smart ‘Rick and Gary’ were" (Kershner interview). But he felt that this was giving him and Figgins too much credit. "The truth of it is, ‘Gary and Rick’ were best friends, having a blast making wine," said Small. "And we just lucked out and were good at it," he said (Kershner interview).

As of 2023, Woodward Canyon’s bestselling wines were the same ones that launched the winery’s reputation four decades earlier: the Cabernet Sauvignon, and the Chardonnay, using some of those original vines planted on the farm back in 1978.

More: Excerpts from Jim Kershner's interview with Rick Small