On August 5, 1967, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas leads a protest against the Kennecott Copper Corporation, which has announced plans to develop an open-pit copper mine in the Glacier Peak Wilderness near Darrington. Activists have invited Douglas to a protest gathering at the Sulphur Creek Campground along the Suiattle River. Douglas welcomes the opportunity to speak about wilderness values; a Washington native, he knows the area of the proposed mine firsthand and has written of its virtues. Among a crowd of hundreds, Douglas warns about what would be lost if Kennecott proceeds with its mine, stating "just because something’s legal doesn’t necessarily mean it’s right" (Morris, 3).

Son of Yakima

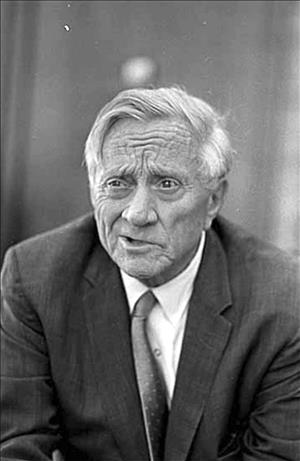

U.S. Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas (1898-1980) welcomed causes off the bench. Nothing attracted him more than protecting wild places in the Pacific Northwest. Hailing from Yakima, Justice Douglas sat on the nation’s highest court but felt just as comfortable high in the Cascade Mountains. In 1967, local activists invited Douglas to a protest outside Darrington, near where Kennecott Copper Corporation planned an open-pit copper mine. He accepted, and the event reflected important political values and tensions of the time.

This was not Justice Douglas’s first trip to the Glacier Peak area. After a hike in the 1950s, he wrote eloquently about the area in his 1960 book, My Wilderness: The Pacific West. There, he touched on themes he preached his entire public life, such as the strength obtained from time in nature and the beauty of wilderness. Threats to special places like Glacier Peak roused Douglas. In the mountains at a place called Miners Ridge, mining companies sought valuable minerals; along the Suiattle River, timber companies coveted timber. But Douglas argued, "The aesthetic values of the wilderness are as much our inheritance as the veins of copper and coal in our hills and the forests in our mountains" (Douglas, 160).

There could be salvation by protecting this land as wilderness. "If the valleys and ridges of this Glacier Peak area are sealed from commercial projects, we will have forever in America high country of enchantment," he wrote. "Those who search them out will learn that an emptiness in life comes with the destruction of wilderness; that a fullness of life follows when one comes on intimate terms with woods and peaks and meadows" (Douglas 165). Someone who thought that could not abide the idea of an open-pit mine in the middle of wilderness.

Kennecott Copper

Kennecott Copper acquired mining patents in the early 1950s near Miners Ridge and the iconic Image Lake. The Forest Service had long managed the area as a roadless recreation area, but the agency could not stop mining. When the Forest Service made it a wilderness area in 1960, and even after Congress strengthened that designation with the Wilderness Act of 1964, mining could not be prohibited. One of the compromises included to pass the Wilderness Act through Congress allowed existing mining claims to be worked and further exploration for new claims until 1984. When Kennecott announced in late 1966 that it was planning to open a new mine, it initiated the first test to see how the so-called mining loophole would work.

David Birkner, a conservationist with the Statewide Committee to Stop Kennecott Copper, invited Douglas into potentially hostile territory. At least some parties in Darrington favored the mine and wanted the protestors to leave. A logger named Chuck Neidigh called them a "bunch of birdwatchers ... trying to take something away from those who have to work for a living" (Jones). A sign reading "Welcome Kennecott" greeted anyone traveling through the timber town. Recently, some mills had closed, so the promise of jobs encouraged residents and politicians such as state representative Henry Backstrom, a Democrat from Arlington who thought the mine would "be a shot in the arm for the working people" (Morris, 3). Backstrom suggested that after the mine closed, the open pit would fill with water and be a beautiful lake itself. These sorts of divisions became even more pronounced in the coming decades.

"For the Spiritual Side of Man"

If the town offered a cool reception, the Sulphur Creek Campground near the end of the Suiattle River Road provided a welcome atmosphere for Douglas. The media characterized the gathering as "a band of 150 adults, kids, dogs, and an assortment of people wearing beards and beads" (Morris, 3). Backpackers, conservationists, and student activists gathered among the trees and then walked up the trail. After hailing the wonders of wilderness and listing threats to it, Douglas pleaded with the activists, "Let’s not turn everything into dollars. Let’s save something for the spiritual side of man" (Jones). Wearing a flannel shirt and standing with a crowd circling him, Douglas inspired action, claiming, "just because something’s legal doesn’t necessarily mean it’s right" (Morris, 3). This statement coming from a Supreme Court justice, symbol of the highest law in the nation, stood out. But Douglas and those around him thought too much was at stake.

As had happened elsewhere, Justice Douglas brought needed attention that supported the conservation cause. This so-called camp-in galvanized the Northwest public on behalf of wilderness and was part of a successful campaign to create North Cascades National Park the following year – and to prevent Kennecott from digging its open pit. Other protests and factors played a role, but Justice Douglas’s efforts stood out as a high point in the campaign against Kennecott.