John Rogers, who served as Washington's third governor from 1897 until 1901, was the state's only Populist executive. Despite concerns that he would be an activist administrator and bring embarrassment or even harm to the state, he proved to be a prudent and capable one. He was reelected in 1900 as the state's first Democratic governor but died unexpectedly in December 1901, nearly a year into his second term. Ironically, he is remembered less for his gubernatorial work than he is for his legislative success in 1895, more than 18 months before his election, in drafting and obtaining passage of what is colloquially known as the "Barefoot Schoolboy Act." The act was the first in the state to provide a taxation method for the state's public schools.

Beginnings

John Rankin Rogers was born September 4, 1838, in Brunswick, Maine, to John Rogers (1809-1882) and Margaret Green Rogers (1816-1897). He was the first of six children born into the family. He completed his schooling at age 14 (which was common in the nineteenth century) and moved to Boston to apprentice at a pharmacy. In 1856 he traveled to the South to visit relatives in Mississippi and Alabama and ended up staying. He managed a pharmacy in Jackson, Mississippi, for approximately four years, and later moved 16 miles south to Terry's Station (now Terry), Mississippi, where he managed a pharmacy and operated a post office. He saw slavery firsthand during his years in Mississippi, and he later wrote of these experiences and compared them with the plight faced by poor laborers in the late nineteenth century to make his argument for economic equality for all.

By 1861 Rogers had moved north to Cumberland County, Illinois, and that same year he married Sarah Greene (1840-1909). They had five children: Frederick (1863-1941), Edwin (1865-1932), Albert (1867-1947), Carolyn (1870-1961), and Helen (1874-1960). He farmed and taught school for a number of years, and in 1876 the family bought a farm in Harvey County, Kansas, roughly 25 miles north of Wichita. They were in Kansas for 14 years, and during this time Rogers served in several local political offices, including county commissioner. He was an organizer of the local Farmers Alliance, a group that assisted farmers in creating cooperatives that increased their bargaining power with buyers and sellers. He also held an office in the pro-labor Greenback Party. In 1887 he became editor of the Kansas Commoner, which promoted agrarian reform and government-supported redistribution of farmland.

Rogers moved to Puyallup in 1890, where he again operated a drug store. A prolific writer, he published a half-dozen pamphlets between 1892 and 1901 discussing Populist issues of the day, as well as a novel about farm life. Populism, with its call for government intervention designed to bring more power and wealth to the working class, was gaining ground in the United States by the early 1890s. It was brought about by the effects of rapid economic expansion and industrialization in the United States, which had begun more than a decade earlier, resulting in a redistribution of wealth that favored management and owners while worsening conditions for the working class and rural residents.

The urgency for change accelerated after the Panic of 1893. A serious four-year depression followed, one that since has been exceeded in severity in the United States only by the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Populists' ideas began gaining more traction, and some of them were elected to public office. This included John Rogers, who was elected to the legislature in 1894 and assumed office in January 1895, where he wasted little time drafting and introducing legislation that became popularly known as the Barefoot Schoolboy Act. It became his signature achievement.

Barefoot Schoolboy Act

The federal law that created Washington Territory in 1853 set aside two sections of land (equal to roughly one square mile) in each township for public schools. This was far larger than what was needed for a school, and the townships sold small parcels of land from the sections to raise money to build them. This worked well for the territory's larger communities and cities, but not for its rural areas. The 1880 Washington Territorial Census showed that just 72 percent of the children living in the territory were enrolled in public schools – and this was a considerable improvement from the 1870 census, when only 52 percent of the territory's students were enrolled.

Washington became a state in November 1889, and its new constitution mandated that the legislature provide for a general and uniform system of public schools. Though the document mentioned a state tax for common schools, funding was not specified, and school funds continued to be raised as they had been before. Larger cities, such as Seattle, Tacoma, and Spokane, relied on county taxes and taxes imposed by the larger school districts to support their schools, but rural areas lacked a population base to raise sufficient taxes to even build a school, much less support one.

Rogers sought to change this soon after he was sworn into the legislature. He drafted and introduced House Bill 67, titled "Providing for Apportionment of School Fund," but it soon became known as the Barefoot Schoolboy Act. A 1905 article in Olympia's Morning Olympian says that Rogers often used the term "barefoot boy" in his early speeches about the bill, and the nickname eventually caught on. The act required the state Board of Equalization to levy a tax on real property, not to exceed four mills per dollar, which would equal six dollars for each school-age child residing in the state. The legislation further mandated that the state auditor would apportion the school funds to the state's counties based on the number of school-age children residing in each county. In an 1896 Seattle Times article authored by Rogers, he explained why state funding was preferable to the taxation scheme that it replaced:

"These cities thus possessed a special privilege, just such a privilege as a wealthy man might hold who should be allowed to use the school tax paid by himself for the education entirely of his own children. Possessed of these special privileges there could not be in this state a 'general and uniform system of public schools'" ("Barefoot Boy Bill").

The big cities fought the bill, and several versions were voted down, but it finally became law on March 14, 1895. Rogers's original draft had called for a six-mill-per-dollar tax, which would have raised $10 for every child of school age, whether enrolled or not. Though a smaller amount of $6 per child was passed in 1895, by 1901 the tax had been increased to $10.

Washington's First (and Only) Populist Governor

Rogers entered the governor's race as a Populist candidate in 1896. It was a desperate time both for the state and the country. The depression had been underway for three years, and in the 1890s there was no government safety net. Worse, there was no end in sight. An alliance of Democrats, Progressives, and free silver Republicans formed what became known as the "fusion coalition" and nominated Rogers as its gubernatorial candidate. Though he was known among state political figures for his success with the Barefoot Schoolboy Act and was recognized as a leading Populist, he was still largely unknown to the general population. Additionally, there were suspicions about Rogers and the fusionists and their call for more government intervention to bring about economic equality. (Other fusionist ideas included direct election of U.S. senators, the initiative and recall, and woman suffrage – all which became state law in the early twentieth century.) Nevertheless, his message resonated with the voters. He gathered 55 percent of the vote in November, with a comfortable 14 percent majority over his Republican opponent, Potter C. Sullivan.

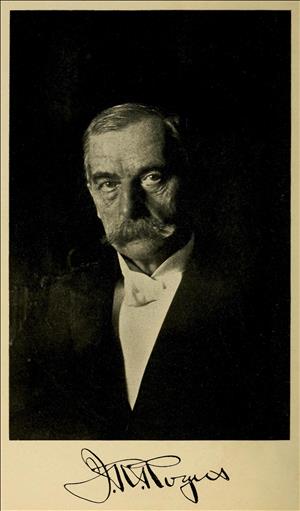

Rogers was sworn in as the state's third governor by Chief Justice Elmon Scott (1853-1921) on January 13, 1897, in a simple ceremony in the House chamber attended by both legislative members and as many spectators that could crowd in. The Seattle Times acknowledged the momentousness of the occasion, writing: "For the first time in the history of the (C)ommonwealth of Washington, including its territorial and state career, the executive and legislative branches passed from the control of the Republicans" ("The Message"). Slender and tall, with thinning white hair and a mustache, Rogers cut a stern appearance as he addressed the legislature after his swearing in and reminded it of the hard times that the state faced:

"Times are hard, we say, and property has depreciated below the value it should justly hold. Men vainly seek employment, which, if found, is not adequately remunerative. Anxious wives and mothers look with fear to the daily diminishing family store. Mortgages cover much of the real estate, and the hearts of strong, brave men sink within them as they view with moistened eyes the needs of helpless children for whom they are called to provide" ("Two Messages …").

He asked for state taxation and funding to support the Barefoot Schoolboy Act, and he called for free textbooks for all children. He decried high freight and passenger fares on the state's railroads and argued for a bill to establish a railroad commission. The legislature responded by setting a maximum per-ton freight rate on the state's railways. Rogers also advocated for free homes for every family in the state. The legislature didn't touch that one, but it did pass legislation protecting debtors from foreclosure and garnishment.

In his message, Rogers commented on the increasing number of state agencies and suggested that some be consolidated or eliminated, and despite the poor economic conditions, he called for reductions in state spending. He talked about three recent mining disasters in the state's coal mines, which had killed more than 100 people, and he requested legislation authorizing mine inspections. The legislature subsequently passed a bill that authorized a position for a state coal mine inspector. He asked that the state's tax laws be amended, arguing that they "cast the heaviest burden on those least able to bear it" ("The Message"), and the legislature passed a new law that restructured taxes to an extent.

Later in 1897, the economy began to improve. The state's port cities, especially Seattle, got an additional boost that summer from the discovery of gold in the Klondike region of Canada's Yukon Territory. Almost overnight Seattle became a major departure point for those headed north, which led to the creation of new jobs and opportunities for many. Though the gold rush turned out to be relatively short-lived, the economic stimulus it provided was more long-lasting.

The recovery made the fusionists' message less compelling in the 1898 election campaign. The coalition had been born because of a crisis, but this was passing by the autumn of 1898. To add to the improving mood, the United States had easily prevailed over Spain in the brief Spanish-American War fought earlier that year. (Rogers annoyed some by picking an Army officer, instead of one from the National Guard, to train recruits when the 1st Regiment of the Washington National Guard was mobilized and sent to the Philippines, but his decision was later lauded.) Confidence was returning, and the atmosphere in the 1898 elections was markedly different than in 1896. This showed at the polls in November, when the Republicans regained control of the House and whittled down the fusion coalition's majority in the Senate, impacting Rogers's ability to get significant legislation passed in the following session.

The governor greeted the new legislature in 1899 by touting his success in reducing the state's debt by a quarter and cutting the state budget by nearly in half during the first two years of his term. He was especially proud of the work done by the new state Board of Audit and Control (later the Board of Control) in reducing operating costs in the state's institutions. The board was chaired by his friend and protégé Ernest Lister (1870-1919), who later became Washington state's eighth governor. However, Rogers asserted that more work remained to be done. He urged further reductions in state spending as well as increased corporation and inheritance taxes, and he proposed an income tax on the state's wealthier citizens. The tax proposals went nowhere, though the legislature did pass a few nominal tax cuts that benefitted the state's poorer citizens.

A Close Reelection

With a comfortable economy and a steady record to show, he might have been expected to coast to reelection in 1900. But with the depression now behind them, Washingtonians leaned back toward their Republican roots. Running as a Democrat, Rogers defeated the Republican candidate, former state senator John Frink (1845-1914), by a slim 2 percent margin, and he prevailed with only a plurality of less than 49 percent of the total vote. It was a lonely victory: Republicans won every other statewide contest that year.

He began his 1901 message to the legislature the following January by thanking the state's voters for returning him to office, then pointed out that because of his cost-saving measures, the state's debt had been reduced from nearly $2.2 million when he took office to just under $1.4 million at the beginning of 1901. His biennial request for the legislature to establish a railroad commission once again failed, and a watered-down bill that attempted to regulate railroad rates also was defeated.

In the state's early history there were many who were unhappy with the capital's location in Olympia, which was smaller than Tacoma and Seattle, and more difficult for many travelers to reach. There was considerable talk of moving it to Tacoma, Seattle, or other cities, and episodic attempts to do so. Voters rejected an 1890 effort, but in 1901 it came up again. A bill for the question to appear on the 1902 ballot failed to pass in the legislature, but even if it had, moving the capital was an expensive proposition and the frugal Rogers likely would have vetoed it. (Four years later, Republican governor Albert Mead [1861-1913] vetoed a similar bill, partly on comparable grounds, that would have moved the capital to Tacoma. It was the last serious attempt to move it.)

Meanwhile, the wood-frame capitol building in Olympia, which dated to 1856, was no longer adequate. It was decrepit, cramped, its roof leaked, and the interior was drafty. There had been talk of building a new edifice for nearly 10 years, and a foundation for one had been laid before funding ran out in the mid-1890s. The legislature approved additional funding in both 1897 and 1899 but Rogers vetoed the bills, arguing that a new building was too costly. Instead, in both his 1899 and 1901 legislative messages, he advocated that the state buy the existing Thurston County courthouse in Olympia, an attractive, roomy structure that he argued could be modified to fill the need for a new building. The 1901 legislature approved the purchase of the courthouse for $350,000, but Rogers did not live to see it moved to its new home and repurposed.

An Untimely Death

Rogers came down with a bad cold about a week before Christmas 1901, which quickly progressed to pneumonia. Though his condition was known to be serious, it was stable for several days and there was not a sense that death was near. Thus, it was a shock when his illness suddenly worsened on December 26, and he died at 8 p.m. that evening. Lieutenant Governor Henry McBride (1856-1937), a Republican, became governor.

The day after Rogers's death, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote an insightful editorial summarizing its thoughts of his five years in office:

"It can be said of Gov. Rogers that, of all the men who were carried by the advancing wave of Populism five years ago into high executive office in many of the Western states, he was distinctly the most capable and carried into effect fewer of the destructive policies that he represented ... He showed himself, also, open to educating influences and capable of learning statecraft. He dismissed not a few of the strange theories that he originally held. He modified to some extent his opinions on abstract questions that experience has not solved. He learned practical politics with extreme rapidity ... He proved that he was not an iconoclast and never threatened at any time to bring danger to the state. The John R. Rogers who died yesterday was not the John R. Rogers who was elected governor in 1896" ("Death of Governor Rogers").

Yet despite his accomplishments and the respect that he gained during his life, Rogers is little remembered by Washingtonians today. Perhaps the most inspiring memorial that can be written here is to quote the ending from his 1897 message to the legislature, words that are equally as relevant in 2024 as they were more than 125 years ago:

"Although it is clearly apparent to all thinking men that the people of this country are within the next few years to pass through a most critical period of national existence, I have a firm and abiding confidence in the wisdom, the justice and the abilities of the great American people. They will safely surmount all opposition, for against the threatening difficulties which may seem to the timid to bar their advance they will [a]ppose the purpose of an honest intention and an earnest aspiration. The spirit of the fathers animates them; for them there is no such word as fail; they have hitched their wagon to a star, the Star of Hope; and the hope of humanity in them shall never perish" ("The Message").