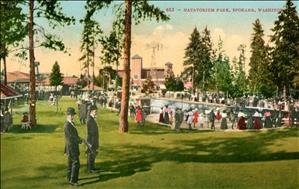

Natatorium Park – "Nat Park," as it was affectionately known – was a popular Spokane destination for nearly 80 years. Located along a bend in the Spokane River several miles from the city center at the west end of Boone Avenue, the park opened on July 26, 1890. It was Spokane's first trolley park, developed in the rich tradition of American trolley parks as recreational amusement centers. Originally called Twickenham Park, it would be renamed Natatorium because of the popularity of its indoor swimming pool. The city's first professional baseball team was initiated on the park's grounds, and the swimming pool opened there in 1893.

Evolution of the Park

Natatorium Park was first and foremost a Spokane Street Railway trolley park. Street railways across the nation had entered the amusement business to further their profits; what began as a method of transporting workers to and from jobs now doubled as a means of transportation for pleasure seekers. At the time, electrical companies often charged transit firms a flat monthly rate regardless of how much or how little electricity was used, so streetcar owners sought to increase ridership during slower weekends and evenings. It followed that there should be a pleasant destination spot for the public. Thus, the park concept was born.

Spokane grew briskly in the 1880s, and with the sale of suburban land a convenient means of travel was needed to and from the heart of the city. Real estate entrepreneurs followed the examples of others and introduced street railways. The city’s first streetcar line was the horse-drawn Spokane Street Railway. John D. Sherwood, a successful developer in Spokane’s early history, financed the line, which carried passenger traffic from the Northern Pacific station across the first Monroe Street Bridge. By then, Spokane Falls, as the city was called, had become the county seat and was emerging as an urban center. The population surged from 350 in 1880 to 19,922 in 1890.

Herbert Bolster arrived in Spokane Falls in 1885, platted 12 blocks of lots for sale in what was known as Twickenham West and adjacent additions at a bend in the Spokane River near the end of the streetcar line, and built a double-decker bridge across the river at the west end of Boone Avenue. The top deck supported streetcars; the bottom deck was a roadway for horses and carriages. The streetcar line continued to a forested ridge above the river, where the park opened in 1890. Bolster, a real estate agent for the Twickenham additions, also was one of the organizers of the Washington Water Power Company (WWP), which provided power for the streetcar railway. The railway was a selling point for the lots: Riders on the 10-miles-per-hour streetcars reached Twickenham just 20 minutes after leaving downtown, which made travel convenient. It eliminated the need for the public to have to feed, harness, and hitch up their horses. The Twickenham additions were intended to entice commuters seeking respite from the bustling city.

In 1892, three years after a fire burned much of the downtown area, the Spokane Street Railway (a subsidiary of WWP) purchased the park, its 51 acres, and Herbert Bolster’s streetcar route. It sought revenue from the "end of the line" park, which had been built in the spirit of New York’s Coney Island to increase passenger traffic during evenings and weekends. The park was leased to Ernest I. W. Eggert and Henry Stege, who further expanded the entertainments offered there.

The park would change hands many times over the years. The first transfer was from the Spokane Cable Railway to the Spokane Street Railway. [Here it is important to mention the corporate relationships between the early companies related to the park: 1) Herbert Bolster & Company; 2) Spokane Falls Land and Improvement Company; 3) Spokane Cable Railway; 4) Spokane Street Railway, and 5) Washington Water Power Company. These companies were related through their owners’ shared financial interests in Spokane’s developing real estate markets, street railways, and electrical power plants. By 1899, they would consolidate into the WWP.]

In 1903, entrepreneur Jay P. Graves (1859-1948) became a competitor in Spokane’s streetcar business. He bought the Spokane & Montrose Motor Railroad – the only city line not owned by WWP – and reorganized it as the Spokane Traction Company. The City of Spokane granted Graves a franchise that allowed him to compete with the Spokane Street Railway. He continued to run in stiff competition with WWP. He merged the Inland Empire Railroad with the Spokane Traction Company, attempted to force a merger with WWP, and tried to entice the City League baseball club away from Natatorium Park to a site near his own Recreation Park. The move was turned down by the league.

Washington Water Power’s intention was to close the park, plat the land, and sell it as soon as real estate prices warranted. According to a WWP official, the park had outlived the purpose for which it was built. But by 1914, the park was still unsold, and a change in the state of the world further affected WWP’s plans to do so. World War I was underway and the U.S. was now being drawn in as well. Activities at Natatorium Park were influenced by the attitudes of the general public as people came to accept, and then gear up for, World War I. The park satisfied the need to play, which resulted in increased attendance.

Baseball

To attract riders and more people to the park, baseball was the attraction that overshadowed all others. In 1890 a baseball field was added to the park and the Spokane Baseball Club was formally incorporated on March 29, 1890. Bolster was the first president of the Spokane Baseball Club and most likely an influential force in securing the location of the baseball grounds.

After a fire in 1899, in 1900 the Spokane Amateur Athletic Club (SAAC) removed stumps and cleared a field to make it suitable for baseball and football. They also built a grandstand and fence, which met with WWP's approval. On weekends and holidays, May through October, baseball games were a park mainstay. Capacity crowds were common and betting on games was popular. The Spokane team for a time became part of the Pacific Northwest League. In addition, a city league made up of teams sponsored by local businesses also played a schedule of games. The players received free transportation to the ballpark on game days and earned salaries from $30 to $100 a season in addition to free uniforms and equipment.

Not until 1918 did Natatorium Park become tainted by war. Baseball was threatened when Newton D. Baker, U.S. Secretary of War, attempted to reduce participation to just Major League games during the war; he felt if players were healthy enough to play ball they could certainly march to war. His plan was overruled, and barnstorming semi-pro teams became a staple on the Natatorium Park ballfield. Black teams such as the Chicago Union Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs did well on the circuit; they all put Spokane on their schedules. New York Yankees star Babe Ruth played in an exhibition game on October 17, 1924. He hit a ball over the sign on the center-field fence. The grandstand crowds continued to number two to five thousand strong, particularly for the barnstormers.

Pool and Other Amusements

At the far end of the park at the Spokane River’s edge, a swimming pool opened on July 15, 1893. It was a hit with kids, adults, and soldiers from nearby Fort George Wright for public swimming as well as races. In 1910, the original pool was replaced with what was referred to as "The Plunge" – an Olympic-size pool that sloped from 2 to 12 feet deep, had a domed roof, and was surrounded by 300 changing rooms. The first year it took 319 tons of coal to heat it. The Plunge was filled with well water, tapping the same underground water flow that supplied the city of Spokane. It never lacked for patronage in the summer.

In 1907, well known amusement park designer Audley Ingersoll took over Natatorium Park. At that time, rival entrepreneur J. P. Graves was advocating for what was termed a "White City" – the title given to the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. That fair offered hope that urbanization could provide a "satisfying, clean, and habitable" form of life. Besides integrating technology with fun, the Chicago World’s Fair influenced the future development of amusement parks. Visitors would pass from the grime of the city through the portals of a glistening White City and be invited to imagine a better world. It gave hope and fed the dreams of a nation beleaguered by the harsh realities of urbanization. The amusement park provided a temporary emotional escape from the cares of the world.

Ingersoll leased all of Natatorium Park’s grounds from WWP with the exception of the baseball grounds and the Dutch Jake Goetz movie picture stand. The lease was issued in order to emphasize the amusement aspect of the park with the influence of the ideals of the White City. Many new attractions were added during his involvement with the park, but by the end of 1908 Ingersoll was heavily in debt and WWP became the beneficiary of his efforts.

Ingersoll had installed the scenic railway and Ye Old Mill rides and would greatly expand his operations. There was the scenic railway roller coaster (also known as a figure-eight); a three-way toboggan slide; Dutch Jake’s open-air theater showing of the first full-length feature film in 1903, The Great Train Robbery; and "polite vaudeville" played in the new rustic theater. The other park concessions included the Jack-Rabbit, which was the loudest and most popular ride in the park; the Joy Wheel, a spinning wheel in which you were required to laugh, later renamed the Nut House; the Dragon Slide, which was a long, curvy wooden slide that was a fire-breathing monster with its curled green tail and open fanged mouth; the Tunnel of Love; Dodgem cars; Custer Speedway; Fun in the Dark; the Whirl-o-Plane; and the Shoot-the-Chute.

At the top of the Shoot-the Chute, a flat-bottomed boat was brought around by a turntable and slid down a track into a huge artificial pool with the bottom of it lit with colored lights. The pool was surrounded by a lighted six-foot walkway and was the centerpiece of the park. It proved to be one of the most popular rides in the concession area. A "Galveston Flood" building was built near the old figure eight which showed in miniature the heavy rain, rising, and sweeping away houses. There was the "darkness to dawn" building that was supposed to emulate creation. Next to that was the Foolish House with its twisting passages, moving floors, and inclines. There was also the House of Trouble, which was a maze.

Smaller concessions included a shooting gallery, a Japanese ball game, glass blowing, a laughing gallery with distorted mirrors, and a penny arcade. There was Jacob Goetz's Hale’s Tour of the World building, which contained two imitation trains where moving pictures from all over the world were seen as well as a number of slot machines for pictures and stamps. There was an open-air theatre with seating for 1,200. In addition, weekly balloon launches were offered. The Ye Old Mill was updated with new scenes including a Japanese flower garden, pastoral scenes, an Indian camp, cotton fields, and a hall where a small orchestra played every day. An artificial menagerie with moving animals completed the effects. The Scenic Railway continued its 2,200-foot run. A Lover’s Lane was designed to run along the Spokane River toward the old Twickenham Bridge to Fort George Wright. Dancing had been gaining in popularity and in 1914 the dancing pavilion was enlarged and refurbished. Band concerts were held in the park in the afternoon and orchestras played at night.

World War I and Beyond

Due to the war, WWP decreased its services to conserve manpower and resources needed for battle, consolidated its enterprises, and focused more on furnishing electric power alone. On November 11, 1918, the war ended, resulting in changes impacting Natatorium Park.

Automobiles increasingly forced the city's transportation systems to adapt. Jitneys posed a controversial challenge for Spokane and the street railways. They were the primitive version of the modern bus, and they began to seriously compete for fares in the early 1920s. There were 77 licensed jitneys on Spokane’s streets in 1921; in 1922, WWP applied for its own jitney permit. The advent of the jitneys raised the population’s consciousness to the plight of its railways, and civic groups began to divide into two camps: jitney and street railways. All tended to agree that in order to survive, the street railway companies would have to merge. The failing Spokane and Inland Empire (formerly Spokane Traction Company) was finally merged into WWP’s Spokane Street Railway to form the Spokane United Railway in 1922. At that time, WWP sold Natatorium Park to the Spokane United Railway company.

Throughout the 1920s the park was forced to deal with ever increasing competition from other entertainment being offered by the city’s park system, Down River Golf Course, public pools, and moving picture and vaudeville theaters. Improved communications and transportation were rapidly expanding the boundaries of local recreational opportunities. Now sports fans could fly or go by train to their favorite pastimes. National parks became increasing popular due to automobiles.

By 1926, Natatorium Park was forced to increase its available parking space and built a new road from Boone to accommodate the growing car traffic. Dusty cars from areas beyond paved roads expanded attendance at the park. However, with the stock market crash of 1929, the Spokane United Railway decided that the positives of park ownership did not outweigh the negatives. On March 15, 1929, the Spokane United Railway decided to sell the park. On April 14, 1929, Louis Vogel purchased 42 acres of land, the dancing pavilion, the Plunge, and the airplane ride. He already owned the Whip, the carousel, and the Caterpillar.

Vogel had married Emma Looff, daughter of Charles Looff, who built the carousel, a beautiful example with 54 horses. The carousel was given to the Vogels as a wedding present and installed in the park. Louis Vogel took over operation of the carousel and all other concessions at the park. With the purchase by Vogel, Natatorium Park was no longer a trolley park. Now it was simply a private park owned by an individual, and it happened to be located on a trolley line. It was Vogel’s job to provide his patrons with pleasurable experiences and he did not fail them. He continued to improve existing ride concessions and add new ones. The park was legally deeded to Vogel in 1933. He survived the Depression well and was able to adapt to the automobile by creating a larger parking lot. The park was an athlete’s and sports fan’s paradise. Other entertainments included concerts, dances, picnics, speeches, vaudeville shows, plays, and movies. There was also the midway, with its penny arcades, games of skill and chance, and the thrilling rides.

Streetcar Legacy

For the streetcar trolley lines, Natatorium Park was a natural terminal. The Broadway line turned off at Broadway and Monroe, traveled to approximately where St. Lukes’s Hospital was located, and then swung north to switch onto the Boone Avenue tracks and travel on down the river-bank slope to the park. There, the cars swung around a huge rail loop for their return to town. However, even as early as 1929 the WPP became well aware of a more economical means of passenger traffic transportation with auto buses. In 1933, the streetcars and tracks through Spokane were abandoned as auto buses began taking over.

On August 27, 1936, the old veteran car No. 202 was moved to its final resting place at Natatorium Park and ceremoniously burned, which represented Spokane’s trolley park going up in flames. Car No. 202 had been on the line since 1911, reportedly logged more than 1.6 million miles during its 26 years of service, and was the last of its kind. One of the streetcars was eventually restored. It is the former Washington Water Power Company/Spokane United Railways Brill Streetcar No. 140, part of the restored collection at the Inland Northwest Rail Museum in Rearden, just outside Spokane.

World War II and Changing Times

The World War II days during the Big Band Era were heydays for the Vogels. The troops at Fort George Wright, Geiger Field airmen, and U.S. Navy sailors at Farragut on Pend Oreille Lake took weekend liberty leave in Spokane, and Natatorium Park was a popular destination. But the park began a gradual decline after the war, when the ease of auto transportation to surrounding lakes and the opening of many city swimming pools siphoned business away from the park. These other destinations included Liberty Lake, Coeur d’Alene, Hayden Lake, St. Joe River, Spirit Lake, Newport, Medical Lake, Cheney, Loon Lake, and Sandpoint. Always looking for ways to gain more riders for its streetcar lines, WWP invested in Medical Lake’s resort, Camp Comfort.

When Vogel died in June 1952, his son Lloyd and Lloyd's wife carried on with the business. Like his father, Lloyd was a born showman. It was Lloyd who arranged for such name bands as Kay Kayser in 1941 and Harry James in 1952 to play at Natatorium Park. Well-known band leaders such as Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Ted Fio Rito played at the pavilion. In 1956, Lloyd purchased a pair of live seals. They immediately became one of the park’s most popular attractions.

With operational costs continuing to increase, Lloyd Vogel decided to sell his entire park holdings, the concessions, and the land to the El Katif Shrine of Spokane in 1962. The Shriners purchased the land for $75,000. The park was shuttered for the 1963 season but was re-opened in 1964 following some refurbishment and repainting. Bill Oliver took over running the park for the Shriners from 1965 to 1968, but his tenure was marred in 1965 when a park employee was killed on the Jack Rabbit. The park did poorly in those years and no further improvements were made to attract customers.

In November 1967, the park rides and equipment were offered for sale. In 1968, the rides were dismantled, and the Jack Rabbit was burned on site. A rocket ride was relocated to the playground of the Shoe House Nursery on North Maple Street in Spokane and set on springs. The Rock-O-Plane was moved to Thrill-Ville USA, an amusement park in Turner, Oregon.

In 1968, the El Katif Shrine closed the park, cleared the land, and made it into a mobile home retirement village called San Souci West. The citizens of Spokane didn’t want to lose the Looff Carousel and established an organization to buy it. The asking price was $40,000. Plastic gold rings and "Save the Carousel" buttons were sold to raise the money. The carousel remained in storage for seven years after the park closed. Riverfront Park in Spokane was selected for its new home. In 1975 it re-opened in the park in what had been the German pavilion during the Expo '74 World's Fair.