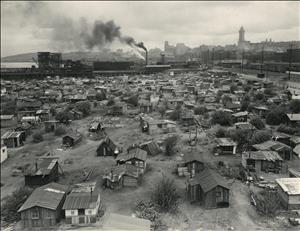

Hoovervilles, also called shanty towns or shack towns, housed thousands of down-on-their-luck men and women during the 1930s. The name was a sarcastic nod to the unpopular U.S. president Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), blamed by many for letting the country slide into a Great Depression after the 1929 stock-market crash. At one point, Seattle had eight shanty towns, mainly in the southern end of the city. The largest encampment, located on tidal flats a few blocks south of Pioneer Square and housing up to 1,200 individuals, began in October 1931 when a group of 20 men led by unemployed logger Jesse Jackson cobbled together rough shacks on a vacant lot that once housed the Skinner & Eddy shipyard. On two occasions, city officials attempted to demolish the shanties but the men rebuilt. As with any other community, there were robberies and fires, stabbings and thefts, births and deaths. There were positive developments as well, including establishment of the Hooverville Workers' College in 1934. Jackson was proclaimed Hooverville's unofficial mayor; there was also a chief of police and an enforcement committee. In 1941, as World War II loomed, the main Seattle Hooverville was demolished to free up land for shipping facilities.

Rise of the Hoovervilles

When the stock market crashed in 1929, it wiped out businesses and life savings nearly overnight and triggered a devastating economic depression that dominated the Northwest for a decade. Businesses laid off workers; homeowners could not pay their taxes or mortgages; renters fell behind and were evicted. While some were able to squeeze in with relatives, others were not as lucky. They crowded into abandoned buildings, lived under bridges and in culverts, or built crude shacks on vacant lots. The term Hooverville was reportedly first used in print media in 1930 by Charles Michelson (1869-1948), publicity director of the Democratic National Committee, who was quoted in a New York Times article about the rise of a homeless community in Chicago. The term, a mocking reference to President Herbert Hoover, under whose watch the Great Depression began, quickly caught on.

There were large Hoovervilles in New York's Central Park, in Chicago near Grant Park, in St. Louis, in Los Angeles and in Portland, Oregon, and Washington, D.C. In Seattle, when individuals mentioned Hooverville, they usually meant the one on the tidal flats adjacent to the Port of Seattle with Railroad Avenue (now East Marginal Way S) to the east, Dearborn Street to the north, and Connecticut Street (now Royal Brougham Way) to the south. The site once housed the Skinner & Eddy shipyards.

Seattle's Hooverville began in October 1931 when an unemployed lumberjack named Jesse Jackson and 20 other men cobbled together shacks on the land. It grew to become "one of the country's largest, longest-lasting, and best-documented Hoovervilles, standing for ten years between 1931 and 1941 … Spread over nine acres, it housed a population of up to 1,200" ("Hoovervilles of the Great Depression"). In his memoir written in 1935, Jackson recounted how men flocked to the makeshift community; 100 shacks popped up in only a month. Then the city stepped in. "The Seattle Health Officials decided our shacks were unfit for human habitation, and posted official notices on our doors, notifying us of the fact, and giving us seven days in which to vacate" ("The Story of Hooverville, In Seattle"). When the men did not budge, law officials arrived with kerosene and attempted to burn them out. The residents scattered, then returned and rebuilt. Another burn-out took place, again with little success. Finally in 1932, after a new city government was elected, officials agreed to a live-and-let-live attitude provided certain rules were followed, such as establishing a committee to oversee safety and public-health concerns.

"The Abode of Forgotten Men"

Although he once called Hooverville "the abode of forgotten men," Jackson, the lumberjack, found the community to be just the opposite. It was, he wrote in 1935, a "colony of industrious men, the most of whom are busy trying to hold their heads up and be self-supporting and respectable. A lot of work is required in order to stay here, consequently, the lazy man does not tarry long in this place. A big percentage of the men have built pushcarts, using two discarded automobile wheels, no tires, and any sort of a rod for an axle. They push these cars about through the alleys of the business section of Seattle, collecting waste materials, mostly paper, which is sorted and baled and sold to the salvage concerns, thus realizing a little each day. Others have made row boats, and fish in the waters of Elliott Bay for a living" ("The Story of Hooverville, In Seattle").

Jackson quickly became the community's unofficial mayor, settling disputes and representing residents' interests in meetings with city officials. He was also one of the few residents with a working radio that he would hook up to a loudspeaker on summer evenings. Happy to escape the reality of their lives for a few hours, the men would gather nearby to hear radio announcer Leo Lassen (1899-1975) call a Seattle Indians baseball game. Besides Jackson, Reuben Washington acted as the chief of police. A sanitation code was imposed by an enforcement committee, "which primarily meant regulating the traffic to the six outhouses set over the beach and reached by rickety wooden catwalks" (The Rise and Fall …").

Hooverville attracted a steady stream of visitors and Jackson often played tour guide. Well-known journalist and future World War II correspondent Ernie Pyle (1900-1945) visited Seattle's Hooverville on assignment, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) sent Secretary of Commerce Daniel C. Roper (1867-1943) to visit the shantytown and report back. Seattle's mayoral and city council candidates campaigned there.

Mr. Hooverville: A Profile

In March 1934, Donald Francis Roy, a University of Washington sociology student, undertook a survey of Hooverville residents, counting 632 men and seven women between the ages of 7 and 73 living in 479 shacks along the tidal flats. To add a sense of realism, Roy joined the community for a while, paying $15 to live in a Hooverville shack from where he conducted his surveys and developed a street plat. His map "divided the shacktown in 12 lettered parts. Each residence was identified by a letter and number whitewashed beside the door. With the 'college boy's' map, the mayor explained, relief payments could be more readily delivered, new residents and drunk ones would have a better chance of finding their way home at night, and the residents, with addresses, could register to vote" (Dorpat, "Now and Then …"). Roy eventually developed a composite picture of those living there, whom he called Mr. Hooverville. According to his data, Mr. Hooverville was primarily white, single, over 40, and an unskilled laborer. "Savings spent, he came to Hooverville in the fall of 1932 to make that community his home. He was primarily a rustler, scrounging for materials to build and maintain it and bumming food from grocery stores" (Dorpat, "Now and Then …").

Six out of 10 Hooverville residents were registered voters, nearly 300 had graduated from high school, and 93 had at least two years of college. Former occupations ran the gamut. There were two lawyers, one medical doctor, and a smattering of barbers, bricklayers, and bankers. Some residents could not make the transition from gainful employment to down-and-out: "The body of John Hedman, unemployed logger, was discovered hanging to the ceiling of his shack in Hooverville. He had been dead two days, coroner's deputies said" ("Two Suicides").

As with any small town, numerous life-changing events played out, from fires and thefts to births and deaths. For all of these, the local papers cited Hooverville as place of residence. Death notices might read: "Emil Dahl, 62, Shack 41-M, Hooverville, [died] July 4, 1935" or "Ellen Addis, 42, Hooverville, [died] July 23, 1936." Birth announcements were treated in a similar fashion: "Mr. & Mrs. Lyle Kinnaman, Hooverville, March 25, 1936, a boy."

Throughout the city, the word Hooverville was shorthand for poverty, desperation, futility. Olympic rower Joe Rantz (1914-2007), who overcame many obstacles to join the famed University of Washington rowing team and win a gold medal at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, was teased repeatedly for his ill-fitting clothes and moth-eaten sweaters. "'Hobo Joe,' the boys snickered. 'How's life down in the Hooverville?' … Joe took to arriving early to change into his rowing clothes before the others showed up" (The Boys in the Boat, Chapter 5).

In an era in which newly arrived immigrants preferred to live with their fellow countrymen, Hooverville might have been Seattle's first fully integrated neighborhood. In addition to about 470 Caucasians, there were 120 Filipinos, 25 Mexicans, 29 African Americans, three Costa Ricans, two Native Americans, two Eskimos, and one Chilean. About 20 percent had been born in the United States.

Establishing a Workers' College

In 1934, unemployed teacher and Hooverville resident Stephen A. Eringis (ca. 1888-1963) founded Hooverville Workers' College, intended to "replace agitation with education" ("Hooverville College Head Fears Political Control") and appointed himself president. Eringis had a bachelor's and master's degree from the University of Washington but had been laid off from his teaching job, forced to support himself and his wife on a government subsidy of $2.50 a week. He landed a job teaching adult education classes at the Warren Avenue School, which paid $7.50 a week, but it was only temporary. It was then that he dreamed up the idea of establishing a Hooverville college.

He visited construction businesses to beg for supplies and appealed to government agencies for funding and support. "Port and county commissioners gave permission to use some land near Charles Street and Railroad Avenue, including some buildings and several tents. Eight teachers agreed to work free. University of Washington professors agreed to lecture" (David Suffia). The city provided free water and electricity.

By the time the college opened its doors on July 2, 1934, 2,000 people had enrolled in its free classes. The curriculum was ambitious but clearly spoke to the community's interests: "social science, social psychology, government, legislation, labor movements, economics, economic history, community history, current industrial problems, international affairs, history, and English" ("Hooverville College Head Fears Political Control").

Additional Encampments

In addition to the main Hooverville, there were seven smaller homeless encampments in and around Seattle. "There was Indian Town on the Duwamish tideflats, and Hollywood on Sixth Avenue South, just south of Lander Street, and another shantytown north of Lander called Reno. There was a high class waterfront settlement called Louisville, and another under the Magnolia Bridge. Harbor Island had its shanties and the city's Sears Tract on Beacon Hill was jammed" ("Seattle's Famous Hooverville").

As Seattle's homeless population crept up to 2,300, city and state officials struggled to cope. In 1934, a plan to move the Hooverville homeless to other camps was put forth by Thomas H. McKee, state director of the Transient Bureau, part of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration:

"We hope to abolish the village of shacks on the waterfront, known as Hooverville, and to distribute the men in shelters and camps. We want the men to get out of [an] unwholesome environment and become self-sustaining. Land will be cleared this winter for five or six new camps for raising agricultural products, rabbits or game birds. We have $40,000 and are seeking tracts of about eighty acres, supplied with water and close to cities" ("Homeless Men to be Assured Federal Care").

The plan evidently did not work, and by 1937 a different tactic was underway: "Gradual elimination of Seattle's shack towns by ordering each shack torn down as it is vacated by its present occupants will be effected by the City Building Department," Supt. H. C. Ritzman advised the Board of Public Works yesterday. The board received a communication from the Gilman Park Community Club complaining against the shack town on land owned by the Port of Seattle between Elliott and Salmon Bays" ("City's 'Shack Towns' Will Be Torn Down").

At times, Hooverville residents banded together to push for change. In a letter dated October 10, 1938, Vance M. Ardeune, representing 25 Hooverville residents and a member of the Workers Alliance of Washington Local No. 1, wrote to the Seattle City Council: "A critical situation has arisen in Hooverville wherein unemployed and aged people with no source of income are being evicted. They have no place to go, and the authorities, having jurisdiction over relief, do not intend to make any provisions for them at all … We are asking that the Mayor and the City Council use the police powers to stop homeless people from being evicted in face of a housing shortage and in face of the coming winter" ("Vance M. Ardeune to City Council").

Conversely, a fair number of Seattle residents saw the encampments as an enormous public health, safety, and aesthetic problem. Petitions and letters arrived at City Hall regularly, requesting their removal. At one city council meeting held in 1938, Mrs. George A. Spencer, a member of the Consolidated South District Clubs, Inc., referred to as a "clubwoman" by The Seattle Times reporter covering the event, pleaded with city council members to shut down the Hoovervilles. "Beacon Hill people must look down on these unsightly shacks. People who live in the shacks get their food from garbage cans. The shacks are made from anything the men can pick up in our neighborhood. Our children at times come across these men. The city officials should live up to their promise to get rid of the shack districts" ("Council Hears Both Sides of Shack Dispute").

Following Mrs. Spencer's speech, 62-year-old George Parish, a Hooverville resident, stood up and spoke frankly about the challenges he and others were facing: "I live in a shack … I try to keep my shack as clean as possible. I don't love living in a place like that. But what am I going to do when I can't get any other place? They tell me I'm too old when I ask for work. I don't want to put a pack on my back and hit the highway. I don't want to live in a box car. I'd leave my shack if I could get another place. And I don't live out of a garbage can"("Council Hears Both Sides of Shack Dispute"). At the meeting's conclusion, the city council deferred taking action.

The Final Demolition

In 1941, as Americans worried about the possibility of engaging in World War II, city officials began to systematically evict Hooverville residents to clear the property for port improvements. On April 10, 1941, a third of the shacks were destroyed and remaining residents were given until May 2 to move out. On May 6, 1941, "the last of Hooverville's residents watched with mingled emotions the destruction of the last of more than one thousand shacks in which many of them have lived since depression days. Huge fires dotted the great tideflat area at the foot of Charles Street on which the shacks stood. A bulldozer monotonously pushed the shacks around until the structures fell into piles of debris at the edge of the flames. The remaining residents, most of whom had loaded their belongings on pushcarts preparatory to moving, were waiting to pay their last respects. The shack town is being demolished to make way for new port improvements" ("Bulldozer, Flames Make Hooverville Just Memory").

Although it seemed to be a new beginning, jobs and decent housing continued to elude many. In a three-hour meeting held June 23, 1941, before King County commissioners, a Hooverville spokesperson noted that only about 50 of the 1,135 displaced Hooverville residents had found a place to live. Four hundred were still unemployed and on relief. Some men were unable to arrange funerals for their loved ones, and one man had lost his wife's ashes during the chaotic demolition of the Hooverville site.