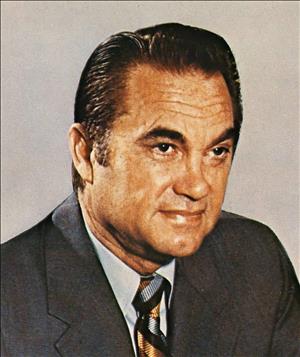

On October 12, 1968, George C. Wallace (1919-1998) campaigns for the presidency in Seattle. He is greeted at Seattle-Tacoma Airport by a crowd that is so enthusiastic it overwhelms security officers and mobs him as he steps onto the tarmac. Three hours later he delivers a roof-raising show, the likes of which Seattle has not seen in decades, to a delighted audience in a packed Moore Theatre.

Wild Welcome

Wallace was a former Democratic governor of Alabama who became nationally known in the 1960s for his anti-integration policies. In 1968 he accepted the presidential nomination of the American Independent Party, a newly formed, ultra-conservative organization, and quickly became the face of the party. Though much has been written about Wallace the segregationist, it's also accurate to describe him as a populist, a man who focused on issues important to the Average Joe who felt he was under siege from the federal government. He criticized allegedly criminal-friendly courts who coddled crooks, "perverts (and) 'pointy-headed' intellectuals" ("Policemen Here …"), and recent advancements in civil rights. His message and the party slogan, "Stand Up for America!" ardently resonated with his supporters, which included not just white Southerners but others nationwide who were disenchanted with the changes and tumult of the 1960s.

Despite a cold steady rain, a crowd estimated at 500 to 700 waited patiently on the tarmac at Seattle-Tacoma Airport for Wallace's arrival on the afternoon of Saturday, October 12. There were several Confederate flags in the audience, including an especially large one held by a man standing atop a nearby loading ramp. The candidate landed nearly an hour late, and shortly after 5 p.m. stepped from the plane. The happy crowd surged past Secret Service agents and security officers and surrounded the former governor, shaking hands and exchanging small talk and jokes. "It was one of the wildest greetings of a political figure seen here," wrote The Seattle Times ("Wallace Welcomed"), and other writers also commented on the intensity of the crowd. The only real opposition came from a lone Black man who held up a small noose when Wallace gave a few remarks. But the arrival was just a warmup for the evening show, which came at the Moore Theatre, located at the corner of 2nd Avenue and Virginia Street in downtown Seattle.

The pre-show entertainment was set to start at 7:15 p.m. with Wallace scheduled to appear 45 minutes later, but the 1,700-seat theater was filled to capacity by 6:30. Thousands of others – the Seattle Post-Intelligencer put the total crowd at 3,000, while The Seattle Times described a larger crowd approaching 10,000 – gathered on the wind-swept sidewalk and street (the day's drenching rain having mercifully ended) in front of the theater. These included not only Wallace supporters but approximately 200 members of the Peace and Freedom Party marching in protest, chanting and handing out leaflets. The threat of violence was a staple at many Wallace rallies in 1968, and occasionally violence did break out. But in Seattle there was only one minor tussle, and it was broken up by witnesses. The opposing sides instead satisfied themselves with baleful looks, taunts, and threats: "Man, I've got my carbines all oiled up to get a couple of you Nazis!" Just wait!" shrieked one Wallace supporter, while another insisted, "He's the only man who can save the country!" ("Uneasy Order"…).

Bantam Rooster

Inside the theater, the crowd was wowed by a pre-show featuring a five-man band playing country music and egged on by Master of Ceremonies (and troublemaker spotter) George Mangum. Twenty-five young women strolled the auditorium with yellow buckets seeking donations. Wallace began speaking at 8:25 p.m., and speakers placed outside of the theater broadcast the performance to those outside. The audience recited the Pledge of Allegiance, sang "God Bless America," and then the candidate appeared. A small man physically (5 feet 7 inches) but nonetheless larger than life, he swiftly took on the 50 or so hecklers in the crowd with characteristic gusto: "If you don't like what I'm talking about – get out. You are the kind that the people of this country are sick and tired of" ("Wallace Steps …"). This brought the pro-Wallace faction in the crowd to its feet, roaring approval and waving Confederate flags, "Stand Up for America!" banners, and clenched fists. The protestors docilely left.

With the hecklers humbled, Wallace got down to the heart of his speech. He decried open-housing legislation which had recently been passed in the country as well as in Seattle, and promised to seek a repeal of the national Fair Housing Act if he was elected. He said he would return control of schools back to Washington citizens, and assured the crowd that there would be no busing to integrate schools. He bemoaned the idea of gun control and predicted, "the next tragedy Congress will try to pass is a law taking guns away from people and the citizens of Washington will be without guns while every thug will have a gun and some will have a machine gun …" ("Wallace Steps …"). He confirmed his support for unions, the police, and for U.S. military superiority in all foreign affairs. And he galvanized his audience with a few classic Wallaceisms. These included promising to "toss all the bureaucrats in the river … and run over the hippies with (my) car if they lie down in front of it" ("Alabama Spoiler …").

Jack Gordon (1921-2010), a civic promoter for Seattle and occasional political writer, wrote of Wallace's rapport with his audience: "Watching the crowd at a Wallace rally is almost as good as watching the showman himself … It's funny in a grim, tragic way" ("Alabama Spoiler…").

Though Wallace was never expected to carry Washington in the election, polls at the time of his Seattle appearance showed he had as much as 12 percent of the vote in the state. (He ultimately gathered 7.4 percent of Washington's vote in the election the following month, considerably lower than the 13.5 percent he received nationally in the election won by Richard M. Nixon.) This popularity, and his followers' passion, led the Post-Intelligencer to run a front-page editorial the day after his visit. The paper explained why it viewed his candidacy as a threat to the nation and concluded: "When this nation urgently requires greater unity among its diverse peoples – young and old, black and white, rich and poor – Mr. Wallace seeks only further division. This is not the American Way" ("The Most …").