The bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan in December 1941 set in motion a series of events and decisions that led to what has been called the worst violation of constitutional rights in American history: the expulsion and imprisonment of 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry from the U.S. West Coast. Two thirds of them were American citizens

The U.S. government wasted no time in clamping down on the 9,600 Japanese Americans in King County. On the evening of December 7, the FBI began to arrest Issei (first generation Japanese) and a few Nisei (second generation), including Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers, officials, and leaders of community organizations whom the FBI considered potential spies.

In the following days, Japanese were ordered to stay away from railroad tunnels, highway bridges, and radio stations. Travel was restricted. Issei business licenses were revoked and bank accounts were frozen.

The push to expel the Japanese was centered in California and led by white farmers. In many ways, the antagonism merely continued nearly a century of hate and exclusion campaigns, first against the Chinese and then the Japanese. California state Attorney General Earl Warren, the future Supreme Court Chief Justice, was among those who asserted that the absence of Japanese "fifth column" activity (absence of activity by any group secretly in sympathy with Japan) on the West Coast was evidence that they were secretly planning another attack.

In Seattle, local Japanese began to feel the heat. At King Street Station, Japanese redcap porters were replaced by Filipinos wearing large identification buttons reading "Filipino." In early 1942, 26 Nisei women resigned as clerks from Seattle elementary schools after the district received complaints from parents.

Racial Grounds

Lt. General John DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, left no doubt that Japanese and Japanese Americans were singled out for mass exclusion on racial grounds. On February 14, 1942, DeWitt wrote, "The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship have become 'Americanized,' the racial strains are undiluted."

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced evacuation. Both Seattle Mayor Earl Millikan and Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966) declared their support of the removal.

By the end of March, 1942, sites had been determined for "assembly centers," temporary prison camps to be used as holding centers for persons of Japanese ancestry until the people could be moved to more permanent "relocation centers." At the time, 14,400 Japanese and Japanese Americans lived in Washington state, 9,600 of them in King County. The Japanese population of Seattle was nearly 7,000.

Expulsion

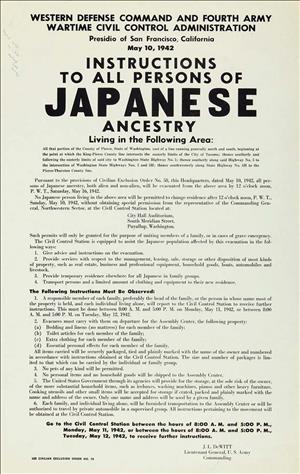

On March 30, 1942, Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island in Puget Sound became the first group in the nation to be evacuated. A few weeks later in Seattle, on Tuesday, April 21, "evacuation" announcements were posted on telephone poles and bulletin boards. The community was to leave the city in three groups the following Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday.

Because the Army limited Japanese Americans to bringing only what they could carry, people made arrangements to store their belongings at churches or at the homes or businesses of friends.

A total of 12,892 persons of Japanese ancestry from Washington state were incarcerated. Seattle and Puyallup Valley Japanese were sent to the Puyallup "assembly center" and then onto Minidoka in Idaho.

Japanese Americans rode in vans, buses, and private automobiles about 25 miles south of Seattle to Puyallup on the site of the annual Western Washington State Fair. They remained there from April 28 to September 23, 1942.

Against a surreal backdrop of a race track, roller coaster, and Ferris wheel, barracks had been constructed in converted livestock stalls, under grandstands, and on parking lots. Boards for floors were laid flat on the ground so that grass grew between the cracks. Some mattresses were issued, but many internees had to stuff straw into canvas bags.

Minidoka

Beginning on August 10, 1942, most Seattleites were sent to the "Minidoka Relocation Center" near Hunt, Idaho, about 15 miles from Twin Falls and 150 miles southeast of Boise. This was one of 10 inland concentration camps filled with Japanese who had been evacuated from the West Coast.

The 7,050 Nikkei from the Seattle area were joined by 2,500 from Oregon and 150 from Alaska -- some of them children or grandchildren of Eskimo women and Japanese men.

The 500 barracks were arranged in 44 blocks, each block with two sections of six barracks, served by a mess hall and a central H-shaped shower and toilet facility. Family rooms varied depending on family size, averaging 16 feet by 20 feet, and were equipped with a potbelly stove and canvas Army cots.

Extreme weather was one of the chief hardships. Winter temperatures often dropped to 10 to 20 degrees below zero, and the thin walls of the barracks provided the barest protection against icy winds. Summer temperatures climbed as high as 115 degrees. After it rained, the dust became a thick bog of mud.

The inmates coped as best they could with the indignity of shared housing and bathing facilities, and the lingering anger and shame of their eviction from lifelong homes and neighborhoods. Minidoka became a little American city with churches, schools, newspapers, a library, fire station, and hospital.

Nisei Soldiers

In January 1943, the U.S. military began to admit Nisei. Many young men were eager to volunteer in the hope of improving the post-war status of their families. Other Nisei and their families agonized over the possibility of military service.

The all-Nisei military units -- the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team -- served with distinction, suffering huge casualties, and helping to end the war in Europe. For its size and length of service, the 442nd was the most decorated military unit of the war.

Concentration camp residents were encouraged to relocate to the Midwest or East Coast and eventually, beginning in January 1945, were permitted to return to the U.S. West Coast.