Seattle's monorail is a mile-long railway that travels between Seattle Center and Westlake Center in downtown Seattle. It opened in 1962 as part of the city's Century 21 Exposition and shuttled visitors back and forth between the fair and downtown. Monorails were not new in 1962, but in the public imagination they were, and given the fair's theme of a brighter future through science and technology, a ride to the fair on the monorail was a ride to the future. Since 1962 the train has continued to serve as a dependable and convenient ride for the masses, and has become a beloved part of the city.

Proposals and Counterproposals

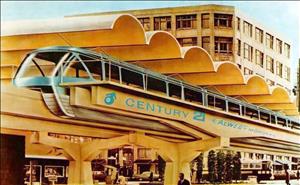

In 1955, Seattle's city government and civic boosters began planning for a world's fair to mark the golden anniversary of Seattle's 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, and by the end of 1956 a site had been selected, much of it located in the city's lower Queen Anne neighborhood. Plans expanded during 1957, and discussions arose about building a monorail to provide transportation to the fair. This was hardly a new or radical idea. There had been monorail proposals floated in the Seattle area in the early twentieth century, and the idea still had traction in the 1950s: In 1955, the Seattle Transit Commission studied whether to build a monorail to run in connection with a proposed tollway from Seattle to Everett. An early proposal for the fair included a monorail to shuttle fairgoers from a 6,000-car parking lot proposed in the Interbay neighborhood, while another envisioned a monorail running from the fair to an amusement pier proposed for the waterfront.

By the summer of 1958 a monorail stretching from the downtown core to the fairgrounds was under consideration, and it was this route that was eventually chosen. Lockheed Aircraft Corporation presented a plan to the Seattle Transit Commission the following January that proposed construction of a roughly mile-long monorail route stretching from the fairgrounds to Westlake Mall, located between 4th and 5th avenues and Pine and Pike streets. In April 1959 the transit commission announced the Lockheed plan had been chosen at a price of $5 million, but the commission later backed away from the proposal before it was finalized. Nevertheless, planning for the fair continued apace, and in late 1959, the opening date was set for April 21, 1962. It would be named the Century 21 Exposition, otherwise known as the Seattle World's Fair.

Whether there would be a monorail at the fair remained an open question as 1960 dawned. The transit commission had previously felt committed to go with the Lockheed plan and had not considered a proposal submitted by the Swedish firm of Alwac International (Alwac) the prior August. In February 1960 Alwac again made the offer. The company would finance, build, and install a $3.5 million monorail system for the fair, which it marketed as the Alweg Monorail System. This included providing two trains, each with four cars, and a two-track structure for the trains to run on. (The Lockheed system, though more expensive, offered to provide three trains, each with three cars.) Alwac would receive repayment from the fair's ticket sales, plus a 25-cent surcharge on each admission. In return, the transit commission would receive title to the monorail after the fair. If ticket sales didn't reach $3.5 million, the transit commissioners agreed to either make up the difference or ask Alwac to remove the monorail at Alwac's expense.

Construction

Alwac and Century 21 Corporation, the entity which managed the fair, signed the final contract on December 22, 1960. The final contract price was $4.2 million, equal to approximately $40 million in 2022 dollars. (Alwac executed a separate contract with the Howard S. Wright Construction Company of Seattle to build the supporting structures and the stations.) A Washington state subsidiary of Alwac, Alweg Rapid Transit Systems (Alweg), directed the actual construction. Ground was broken in a ceremony at Westlake Mall (Westlake) on April 6, 1961, with speeches by dignitaries that included U.S. Senator Warren Magnuson (1905-1989) and Joseph Gandy (1904-1971), president of the Century 21 Exposition. It was the first full-scale system of the Alweg monorail built in the United States (a five-eighths scale monorail was built at Disneyland in 1959), and its design and streamlined trains perfectly fit the space-age, futuristic theme of the fair.

All the monorail pylons were in place by September 18, and installation of the guidebeams began. By the beginning of 1962 the monorail itself was virtually complete -- the final beam was installed on January 9 near Denny Way -- though the trains that were to run on it had not yet arrived from their manufacturing site in West Germany. Much of the effort during the winter months focused on completion of the stations at Westlake and the fairgrounds, which were only 65 percent complete at the beginning of the year. The Westlake station opened on March 24, when both the monorail and the Space Needle opened to delighted crowds, but ticket sales at the fairground station did not begin until the fair opened in April.

Despite heavy rain squalls and blustery winds, an estimated 9,600 people rode the blue train on the monorail's first day (the red train had still not arrived, but did soon after), and nearly 180,000 riders rode the monorail before its christening on April 19. However, this was partly because all Space Needle visitors were required to travel from Westlake to the fairgrounds via the monorail prior to the fair's official opening on April 21. Stairs to the entrance of the Westlake station were located on the Westlake Mall, next to Bartell Drugs' flagship downtown "triangle" drugstore, so called because of its triangular-shaped building. The station itself was suspended above Pine Street. The journey to the fairgrounds was just over a mile long and averaged 25 feet above street level, and the route traveled northwest along 5th Avenue before turning at Denny Way and continued along 5th Avenue N for two blocks before making a sharp turn west to arrive at the fair.

The same trains that ran in 1962 run today. They are both identical in size, each with four cars that consist of two single cars connected on both ends to a train car. The trains measure 122 feet long and 10 feet wide and can each seat 124 people, with room for another 124 to stand. The monorail could travel between Westlake and the fair in 95 seconds at a top speed of 60 mph, though it generally travels at a top speed of about 45 mph. The trains travel on parallel tracks, with the blue car on the west track, the red car on the east. Each train rides on 16 tires, and 48 smaller tires run along the sides of the track to keep the cars aligned on the track and to prevent them from derailing. The additional tires also help ensure a quiet, smooth ride. Driver controls are on each end of the trains, and though Alwac designed the monorail so it could be altered to become fully automated, this has never been done.

The World's Fair

A happy gathering was on hand at the Westlake station on the evening of April 19 to christen the monorail. The wife of Alweg president Sixten Holmquist -- identified by The Seattle Times simply as "Mrs. Sixten Holmquist" -- was given the honor of swinging the ceremonial champagne bottle against the train, which did not break on the first try. As the dignitaries grinned politely and a stone-faced train driver looked on, Mrs. Holmquist winced and tried again. The recalcitrant bottle shattered, the crowd cheered, and it was on to the fair.

The Century 21 Exposition operated for six months: April 21 through October 21, 1962. Monorail fares were 50 cents one-way and 75 cents round-trip for adults, and 35 and 50 cents for similar trips for children. On September 17, more than a month before the end of the fair, enough tickets had been sold to pay for the monorail in full. Alweg had predicted that 25 to 30 percent of the 10 million fairgoers expected would ride the train, but they were low. Nearly 77 percent of the fair attendees -- almost 7.4 million out of 9.6 million -- rode the monorail during the fair. Some of them included Vice-President Lyndon Johnson (1908-1973), former vice-president (and future president) Richard Nixon (1913-1994) and family, and Elvis Presley (1935-1977), who was in town to film It Happened at the World's Fair. Only one accident was reported on the monorail during the fair, and that was on its next-to-last day, when a packed red train overshot the Westlake loading platform and smacked a bumper at a low rate of speed. No injuries were reported, and the train was back in service two hours later.

Downsizing

The 74-acre fair site became the Seattle Center after the fair ended, and developed into a civic, arts, science, and sports mecca in the heart of downtown Seattle. Alwac transferred the monorail system to Century 21 Center (the corporation formed to manage Seattle Center) in 1963. In April 1965, the center sold it to the City of Seattle for $775,150 (equivalent to nearly $7 million in 2022 dollars), though part of the price was offset by forgiving a $414,128 debt that the center owed the city. Further changes came in 1968, when the Westlake station was downsized to a considerable extent. This included the removal of its translucent blue and white scalloped roof as well as two side platforms, which left only one platform for passengers to board and exit the train. Management tried to rectify the problem by installing movable traffic control fences, but crowding continued on busy days at the station until it was rebuilt in the 1980s.

The 1970s were bookended by two significant accidents on the monorail: In July 1971, the red train overshot the stop at Seattle Center station and slammed into a steel girder, injuring 26, while in May 1979, a similar incident at the center injured 15 on the blue train. And a less-than-memorable moment for the monorail came in 1978 when the blue car was repainted a different shade of blue, and the red car painted green, to match Seattle Center's theme colors. Asked if center officials had given any thought to the tradition it was changing, a spokesman replied, "the emphasis was on a coordinated-color scheme" ("Monorail Spruceup"). The new paint job proved so unpopular that the cars were repainted their original blue and red in the 1980s.

By the early 1980s the monorail and stations were both showing their age, and in 1984 the City of Seattle retained Raymond Kaiser Engineers to identify the most urgent tasks needed for the monorail. This also involved the relocation of the Westlake station, which took place with the construction of Westlake Center (an office tower with a shopping mall on its first four floors) between 1986 and 1988. The original Westlake station closed on September 1, 1986, and a temporary station operated a block north, north of Stewart Street, in the interim. To the delight of many, the removal of the old station also removed the overhang above Pine Street that had impeded views and cast a shadow along the street for a quarter century. The Seattle Center station was also renovated, considerably less substantially, in 1988.

On the trains themselves, worn seats and other train materials were replaced or refurbished. Wiring and circuit protection equipment were replaced, while other train technology was upgraded. And the tracks themselves were changed. At the approach to the new Westlake Center station the distance between the two guidebeams was narrowed, reducing the distance between the two tracks and forming a gauntlet of sorts which allowed only one train to enter the station at a time. When completed, the new monorail route was slightly shorter than the original, and now measures just under one mile.

The new Westlake station -- located on the third floor of Westlake Center -- was scheduled to open with Westlake Center on October 20, 1988, but it didn't happen. Three days before opening day, a hinge-pin malfunction that allowed a loading-ramp gate to stick out two inches into the monorail's path was belatedly discovered after it scratched the blue monorail as it pulled into the station during a test run. While that was being fixed, other glitches arose. The new station did not finally open until February 24, 1989.

To the Twenty-First Century

Ever since the fair there had been occasional talk of tearing down the monorail, as well as talk of extending the route. In the late 1990s, it appeared as though the extension talk might come to fruition. A group led by Dick Falkenbury, a Seattle cab driver and community activist, drafted Initiative 41, which called for construction of a 40-mile monorail system resembling a giant "X" and linking Seattle's four corners to downtown. Voters approved the initiative in November 1997, which established the Elevated Transportation Company (ETC) to seek private capital and management to create a new monorail.

The Seattle City Council was less supportive of the expansion efforts, and effectively repealed the initiative in 2000. This led to a second initiative that autumn, Initiative 53, which was designed to create a new, less ambitious plan. It passed handily, and in 2002 the ETC published a plan for a proposed 14-mile "Green Line" route to run from Seattle's Crown Hill neighborhood through Seattle Center and downtown to West Seattle. But financing problems proved insurmountable, which doomed the Green Line. Voters eventually lost patience, and a 2005 initiative for a slightly shorter (10.6 miles) route failed, bringing an end to the long and winding odyssey.

During these years, there was an interesting change along the monorail route when the distinctive building for the Experience Music Project (now the Museum of Pop Culture) was built over a slice of the monorail track, on the curve at the edge of Seattle Center where the track turns to 5th Avenue N. Engineers used global-positioning system technology to map the precise motion of the trains in order to properly build the structure and create a tunnel for the monorail to pass through, which the train has done since the late 1990s (the building itself was finished in 2000).

On May 31, 2004, shortly after 100 to 150 passengers on the blue train left Seattle Center and passed through the tunnel en route to Westlake Center, they heard a loud pop (or pops) and saw sparks. As the train slowed to a stop just outside the tunnel, flames erupted from the rear of the train and the cars filled with thick, black smoke. Passengers were quickly evacuated by Seattle firefighters. There were no serious injuries, though eight riders and a firefighter were briefly treated at Harborview Medical Center. It was later found that a series of events led to a short-circuit that allowed electric current to arc between the rails, which sparked and led to the fire. Another accident occurred near Westlake station on November 26, 2005, when an incoming blue train driver failed to yield to the red train that was departing the station, causing the cars to sideswipe each other above Olive Way on the narrowed section of track. Though there were no serious injuries, both trains were out of commission until the following August.

Monorail Today

The monorail completed its 60th year in operation in 2022. It has continued to serve as a dependable ride through downtown Seattle, especially for those traveling from downtown to events at Seattle Center. The COVID pandemic of the early 2020s closed it for a time, but in 2019 -- the last year prior to the onset of the pandemic -- total ridership was nearly 1.94 million, consistent with the 2 million figure that the monorail has averaged in recent years. Average ridership was higher on weekends, averaging 7,118 riders in 2019, contrasted with an average of 4,647 weekday riders. Fare revenues in 2019 totaled $4.15 million. In 2022, round-trip ticket fares cost $6 for adults and $3 for seniors, disabled, and for children between ages 6 and 18, while one-way fares cost half these amounts.

The monorail cars were designated an historic landmark by the Seattle City Council in 2003, and today Seattle's monorail is the only Alweg monorail still in operation with its original cars. Most recently, work on the monorail included replacement of the original power rail and insulators along the monorail guideway, and the controls were updated on the trains. This work was completed in the early 2010s. The Westlake Center station was extensively remodeled in 2021, resulting in a roomier, more attractive loading area complete with an overhead video screen.