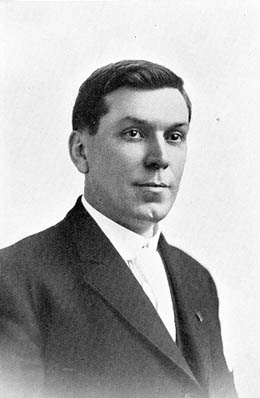

James Delmage (J. D.) Ross is known as the Father of Seattle City Light. A firm believer in the municipal ownership of power utilities, Ross helped design and build the power plant at Cedar Falls on the Cedar River. He is best known for his efforts to secure and construct the hydroelectric project on the Upper Skagit River, which provides 40 percent of Seattle’s electricity. Ross Lake and Ross Dam on the Skagit are named in his honor.

A Self-made Man

J. D. Ross was born to Scotch-Irish parents in Chatham, Ontario, on November 9, 1872. As a boy, he was fascinated with science and physics. He had his own little workshop where he performed countless experiments with electricity (including, at age 11, a recreation of Benjamin Franklin’s experiment of flying a kite in a thunderstorm). Almost all of his knowledge of electricity was self-taught.

He graduated from the Chatham Collegiate Institute in 1891, and taught for a few years, until a physician advised him to get outdoors more. The Klondike Gold Rush was on, and Ross went north to Alaska to stake a claim. He arrived in 1898, prospected for a year and a half, but still felt unfulfilled. He left the frozen north and ended up in Seattle at a fortuitous time.

There’s Power in Power

Seattle City Engineers George F. Cotterill (1865-1958) and Reginald H. Thomson (1856-1949) had spent the past 10 years convincing officials and voters that a publicly owned electric utility was the correct method to supply power to the populace. Monopoly ownership of the city’s primary electric utility had led to high prices and bad service. At the time of Ross’s arrival, the thought of electric utility ownership was in everyone’s minds.

He started out working for private firms and even started his own electrical business, but soon found himself working as an assistant city engineer. On March 4, 1902, voters approved a $500,000 bond to construct a municipal power plant on the Cedar River at Cedar Falls. Ross wasted no time. He walked into Thomson’s office and asked to design and build the new plant.

Thomson asked what experience he'd had in power plant construction. Ross replied: “None. But where will you find anybody that has?” Thomson had no answer to this. Two weeks later Ross returned to Thomson's office with blueprints. The job was his.

Water and Electricity Don’t Mix

In 1905, the completed plant was given over to water superintendent L. B. Youngs. Seattle voters had authorized the city to take over the private Seattle Electric Company's street lighting system earlier that year and the new municipal electric utility was placed under the aegis of the water department.

By 1910, it was apparent that one department could not handle both utilities, and on April 1, 1910, a charter was amended to create a separate light and power department, later called City Light. R. M. Arms was appointed superintendent, but he resigned in just under a year. J. D. Ross was chosen to fill the position - one that he held almost continuously for the rest of his life.

Public vs. Private

From the start, Ross realized that City Light needed to expand its power grid, and he set his sights on the Skagit River, located in the North Cascades. Ross received complete support from his close friend Seattle Mayor Hiram C. Gill (1869-1919). Unfortunately, the East Coast electrical firm of Stone and Webster stood in their way, having obtained temporary federal permits for their own power plant construction along the river.

The permits expired in 1916, and Ross, who had been developing his own plans for a series of three dams along the river, wrote to the Department of Agriculture asking them to grant construction rights to the City of Seattle. Instead, Stone and Webster received a year’s extension.

The next year Ross showed up in Washington D. C. personally with the City’s application in hand. After hearing from Ross that hydroelectric power from the Skagit was sorely needed in the war effort, Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston ordered Stone and Webster to relinquish. The rights to the Skagit were awarded to Seattle.

Work Begins

The smallest dam, Gorge Dam, was built first. Instead of a road, a 25-mile railroad was built from Rockport to Gorge Creek because Ross remained leery about private power firms elbowing their way into the valley. This caused some delays, as did labor troubles, forest fires, mud slides, and other unforeseen events.

By the time the Gorge Dam and powerhouse were completed, the total cost was $13 million. It wasn’t as cheap as Ross had hoped for, but on September 17, 1924, the generators began transmitting power 100 miles to Seattle, after President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) started them from the White House by pressing a golden key. Work on the rest of the project continued.

Fired and Rehired

Next up came the construction of Diablo Dam, located further upstream. Private energy firms, a constant thorn in Ross’ side, continued kvetching to local, state, and federal officials that City Light (or any municipally-owned utility, for that matter) was nothing worse than Socialism in action! Their whining and pouting worked well on Seattle Mayor Frank Edwards (a known agent of Stone and Webster), who summarily fired Ross on March 9, 1931.

Seattle voters saw things differently. They liked the municipal utility for the abundant electricity they received in return for a few dollars. Socialism it wasn’t, and two months after Edwards fired Ross, the voters had a special election and threw Edwards out on his ear. One of newly appointed Mayor Robert Harlin’s first tasks was to rehire Ross on July 14, 1931.

Ross continued with the Diablo Dam project, which began producing electricity in 1936. During this time, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) called him to a membership on the Securities and Exchange Commission. In 1937, Roosevelt appointed him as the first administrator of the Bonneville Power Project on the Columbia River. Even with all these new tasks, Ross continued to function as superintendent of City Light, accepting no salary from the city once he had accepted his federal posts.

Flowers and Birds

City Light and the Skagit River project were the focus of Ross’ lifelong goal – the delivery of cheap power for the public good. Since the people, in effect, owned the municipal power utility, Ross made sure that City Light remained bright in the public eye. He did this through advertising and with tours of the Skagit project.

A lover of animals and flowers (he was a world authority on lilies, and could name almost any plant that grew), Ross did much to enhance the tours for the many visitors. A wide variety of flowers were planted alongside trails and a zoo was built at Diablo. He introduced numerous trees and shrubs, along with many species of birds new to the Skagit valley, where they still flourish.

Another “Ross Touch” along the tour was, of course, electricity. Hidden phonographs and amplifiers piped music throughout the hillsides, and at night the falls were illuminated in a colorful display of lights and motion.

A Friend to Children

Along with his commitment to low-cost electricity and his passionate hobby of botany, Ross’ other joy in life was children. He and his wife Alice M. Wilson (whom he married in 1907) had none of their own, but raised the son of his brother after his death in 1912. They also cared for other unfortunate children, who stayed in their home while going to school.

Ross had a cheery hello for and deep-seated interest in every child he met throughout the day. One child in his neighborhood, whom Ross had aided in some beginning chemistry experiments, became so engrossed in a science project that he unwittingly called Mr. Ross at two in the morning to share his results. The power chief got out of bed and walked five blocks to happily congratulate his young friend.

The Light Goes Out

After the completion of the Diablo Dam, the final phase of the Skagit project was a dam to be built below Ruby Creek, farther upstream. By this time, Ross was in his 60s. He was determined to stay on as City Light head until it was completed, and the full 1,125,000-kilowatt capacity of the Skagit project was delivered to Seattle. Sadly, he wasn’t able to see it through.

In 1939, one year before the first phase of the Ruby Dam project was to be finished, Ross checked into the Mayo Brothers’ Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for an operation. All went well, and afterward he and his wife were in his room joking about their return to Seattle. Suddenly he suffered a massive heart attack. Like a light switch being shut off, he died instantly.

J. D.

City Light darkened as well. Those who worked there loved him, and he was known to all as J.D. (never Mr. Ross). They looked up to him as a friend, a pal, and as the “Father of City Light.” Condolences were sent from Washington D.C. and from across the country.

The next year, the first phase of Ruby Creek dam was completed, and the dam was named Ross Dam in his honor. The new lake formed by the project was named Ross Lake. Ross Mountain, in the heart of the Skagit project he conceived and built, became his final resting place, and later his wife’s. Over their granite-carved tomb is a bronze plate with the words “James Delmage Ross.” Beneath are simply the letters “J. D.” by which he was known best.