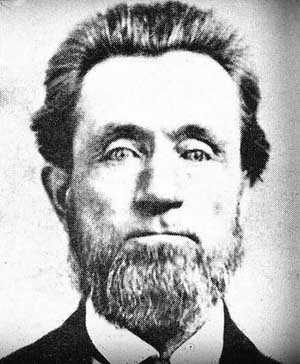

Henry Yesler was a middle-aged man when he arrived at Elliott Bay in October 1852 and quickly established himself as the most important resident of the rain-swept little spot that would soon become Seattle. He had the first steam-powered sawmill on Puget Sound up and running within months, and for several years he employed almost every male settler in Seattle and a considerable number of Native Americans. His mill was early Seattle's only industry, and without it the town's development would have been greatly delayed. For the first 40 years of Seattle's existence Yesler, joined in 1858 by his wife, Sarah Burgert Yesler (1822-1887), played a part in nearly every important civic event and undertaking and held several public offices, although he was largely uninterested in politics. Known as both a generous benefactor and a litigious rascal, such was the respect granted him by contemporaries that his less-admirable traits were largely ignored by chroniclers of the city's early history. Yesler's sawmills were only sometimes profitable, and success in other industries and commerce usually eluded him, but by the time of his death his large property holdings in what had become the city's commercial core made him wealthy beyond all expectations.

The First Forty Years

Henry Leiter Yesler was born in a December sometime between 1810 and 1813 to Henry Yesler and Catherine Stotler of Leitersburg, Maryland, a town founded by his mother's grandfather. Many years later, allegations made in a suit over Yesler's estate claimed that his mother and father were wed only after his birth, and the recorded date of their marriage, December 26, 1810, could support this if he was in fact born that year. However, in several federal censuses Yesler provided an age that would place his birth in 1812 or 1813. It seems unlikely the matter can ever be fully resolved, but it is known that his parents were married only briefly before divorcing and marrying others, and that Yesler remained estranged from his father's side of the family his entire life.

Young Henry was apprenticed to a house carpenter around age 17 and worked at the trade in Leitersburg until 1832. He then packed up his tools and left Maryland, going first to Massillon, Ohio, where he stayed for a year, then traveling as far south as New Orleans and as far north as New York City, working along the way. Yesler returned to Massillon in 1837, met Sarah Burgert, and married her in 1839. A daughter, probably born in 1844, died within a year; a son, George, was born in 1845.

Yesler built two moderately successful water-powered sawmills in Ohio, but came to believe that greater opportunities lay elsewhere. He was drawn to California, where the discovery of gold had triggered a building boom, and in 1851 he headed west, leaving Sarah and his young son behind. He reached San Francisco via the Isthmus of Panama, but historians disagree on his precise movements for a time after that -- even his wife lost track of him and sent copies of letters to different locations, hoping one would find its way to her husband.

Starting Fresh

Yesler spent time in San Francisco and Marysville in California, and in Portland, Oregon, and it was during this period that he decided to build a sawmill in the West. In late 1851 he contacted an old friend and financial backer in Ohio, John McClain, and asked him to order the components of a steam-powered mill and have them shipped around the Horn to San Francisco. California and Portland were rejected as mill sites, the latter due to the difficulty of getting ships across the Columbia River bar. But in San Francisco, Yesler had met a sea captain who told him that Elliott Bay was ideal for a sawmill, the land thick with trees nearly to the shore and deep moorage close in. Yesler decided to take a look, made his way from Portland to Olympia and then paddled up Puget Sound by canoe. In October 1852 he arrived at "New York-Alki" (now West Seattle) at the entrance to Elliott Bay, where the Denny Party had landed 11 months earlier.

Yesler judged Alki unsuitable for a mill and made his way the short distance to the eastern shore of Elliott Bay, where a few rough cabins had been built by William Bell (1817-1887), Arthur (1822-1899) and David (1832-1903) Denny, Carson Boren (1824-1912), and David S. "Doc" Maynard (1808-1873). This muddy little enclave had been given the unfortunate name "Duwamps," but right around the time Yesler arrived, Maynard, to his everlasting credit, changed it to "Seattle." The five men who preceded Yesler had staked claims that took up most of the shoreline, but after learning of Yesler's intentions, Boren and Maynard agreed to give him the land necessary for his plans. The place Yesler chose was by a small peninsula (an island during very high tides) that jutted south near the boundary between Maynard's claim and that of Boren and was separated from the mainland by a marshy tidal lagoon to the east. Duwamish and Suquamish peoples, many of whom lived along nearby shores, called the location "Little Crossing-Over Place," a reference to a trail that started there and led inland (Thrush, 14).

Boren and Maynard transferred to Yesler a strip of land nearly 500 feet wide that ran inland between their claims. He built his mill on the north side of the western end of this strip, which formed a panhandle leading to a 320-acre Donation Land claim he made for himself and his wife on what came to be called First Hill. Part of the strip would be used to skid logs from the heavily wooded hillsides down to the mill. It was known variously as Mill Street, Skid Road, and, finally, Yesler Way.

Yesler's First Seattle Mill

The sawmill equipment, which included a 12-horsepower steam engine, a boiler, and a 48-inch circular saw, had left New York by ship in May 1852. While other settlers built a shed to house it, Yesler sailed to San Francisco to take delivery, and after considerable delay the equipment arrived in Seattle in early 1853. Yesler later said, "we had to throw it all into the water & let it float ashore. The boiler was floated in this way, but the engine was placed on a raft" ("Henry Yesler and the Founding of Seattle"). Once ashore, it was quickly assembled, and the mill cut its first lumber in late March of 1853, using logs from Doc Maynard's claim. Yesler built a crude water-supply system for the boiler, a v-shaped wooden trough that ran from nearby springs to the mill. He later extended this to the end of his dock to supply fresh water to visiting ships.

Before the mill equipment arrived, Yesler had built his famous log cookhouse, a "low, long, rambling affair without architectural pretentions" near shore on the south side of his panhandle (History of Seattle, Washington, 83). It at once became the focus of the settlers' social and civic activities, hosting Seattle's first sermon (by Catholic Bishop Modeste Demers [1809-1871]), its first court case, and its first election. Mill workers would take their meals there, and it was where Yesler lived until his wife came west in 1858. He later described these early days:

"My mill was the first steam saw mill put up on the Sound. Lumber sold for $35 a thousand then; now [1878] for $10. As there was no wharf the lumber had to be rafted from the mill to the vessels ... . After the establishment of the mill which was commenced in '52, the town grew rapidly. We commenced sawing wood under a shed in March '53 — the saw dust we filled swamps with, and the slabs we built a wharf with" ("Henry Yesler and the Founding of Seattle").

Yesler's wharf was a makeshift affair at first, but would eventually extend nearly 1,000 feet into Elliott Bay, greatly facilitating the loading and unloading of visiting vessels.

It was not long before other sawmills were established on Puget Sound, nearly all of them larger and more technically advanced than Yesler's, many owned by interests from outside Washington Territory. By his own admission, Yesler often milled short logs of inferior quality, producing lumber that even he characterized as "cultus," a Chinook Jargon word meaning worthless or nearly so. This was used primarily for sheds, fences, and the like, but the mill also produced enough good lumber to replace the town's first rudimentary log cabins with more substantial frame houses and to supply newcomers' building needs. When demand was high, the mill operated 24 hours a day in two 12-hour shifts and exported its products as far as Hawaii and Australia.

Despite its shortcomings, the importance of Yesler's mill to early Seattle and King County cannot be overstated. It was the settlement's first, and for many years only, industry. In its early days it gave employment to nearly all of Seattle's male white settlers and provided additional income by purchasing timber from their claims. In the words of one historian:

"Yesler's mill did not create the town, yet it did more than any one thing to fix the seat of the place. As the first steam mill, and the first mill of any capacity, it gave a temporary advantage to the town, placing the means of building decent houses and establishing pleasant homes within the reach of the people. The effect of this in fixing the people here was very great" (History of Seattle, Washington, 243).

Although his fellow pioneers were given preference, Yesler also hired many Native Americans to work in the mill, and he gained a reputation for treating them with fairness and respect. Indians worked at the mill in nearly every capacity, although they proved particularly adept at over-the-water work, herding logs into booms and poling them to the mill, then maneuvering rafts of cut timbers out to ships waiting at anchor. There was little cash available, and in lieu of that workers bought supplies from local stores on Yesler's account. Indians were paid with brass tokens that could be redeemed partly in coin and partly in goods. One enterprising fellow, believed to be a Haida from the far north, artfully counterfeited dozens of these tokens and escaped before detection.

The Battle of Seattle

The 1856 Battle of Seattle holds a mythic place in most accounts of the city's early days, but it was in fact a rather minor affair in a much larger conflict. Nonetheless, the hostilities hampered the town's progress significantly by emptying it of a sizable portion of the few residents it had accumulated since 1852. Many who farmed or logged in outlying areas and supported the town's tiny commercial sector also fled.

War erupted first east of the Cascades, where the Yakama Tribe and others rose up against the taking of their lands. In the west, Nisqually Chief Leschi (1808-1858) led members of several tribes who also opposed treaties confining them to small, unsuitable reservations. Some attacked pioneer homesteads and lumber camps, including several in south King County, killing a number of settlers. Forewarned, Seattle's few inhabitants prepared for an attack, using wood donated by Yesler to build a blockhouse. Settler families from other parts of King County decamped to Seattle to seek protection. Marines from the navy sloop Decatur were sent ashore to reinforce the town, while women and children were taken to refuge aboard the ship. Through Natives with whom he had become friendly, Yesler was able to provide advance notice of some of the attackers' plans and helped persuade local Indians to avoid involvement.

The first shots, cannon volleys fired from the Decatur into the dark woods east of town, were loosed on the cold morning of January 26, 1856. Indians shot back with muskets from concealed positions, and fire was exchanged sporadically until about 10 p.m. that evening. The Indians then melted away, leaving behind no evidence of casualties, and only two white men were reported killed. After the attack, additional lumber donated by Yesler was used to construct a second blockhouse and a stockade, eight feet high and nearly a quarter-mile long, surrounding the settlement on three sides. It proved unnecessary -- there would be no further attacks on Seattle. Shortly thereafter, Yesler was appointed acting Indian agent for the area, and he persuaded about 150 Natives to relocate to Bainbridge Island. By the end of 1856 only about 50 Indians still lived in Seattle, most in shacks built near the shore with scrap lumber Yesler donated, and many still employed at his mill.

Two Yesler Families

Meanwhile, back in Ohio, Sarah Yesler was becoming impatient. Lumber prices had collapsed in San Francisco in 1855, and this, combined with the exodus of settlers during the Indian hostilities and increased competition from other mills, brought Yesler's business to a near standstill by 1857. Sarah urged her husband to sell everything and return to Massillon, but he believed things would get better and that he could then liquidate his assets on more favorable terms.

As the Indian threat subsided and the flight of settlers began to reverse, Yesler by 1858 believed it safe, if not entirely convenient, for his wife join him. He built a frame house on the corner of First Avenue and James Street and sent Sarah the funds to move west. He dearly wanted both her and George to come, but as the couple planned to return soon to Ohio, the boy would stay there to continue his education.

In addition to building a new home, Yesler had another situation to deal with. He had been living with a teen-aged Native American girl, Susan, believed to be the daughter of Sucquardle, a Duwamish hereditary chief known to the settlers as Curley or Curly Jim. In 1855 she had given birth to a daughter, Julia (1855-1907). Births were not then formally registered, but Yesler confirmed paternity by openly living with and supporting mother and child. With Sarah coming to town, new arrangements were needed, and Susan and Julia went to live with another settler, Jeremiah Benson (d. 1907). A dozen years later, Julia was listed as a member of the Benson household in the 1870 federal census. A territorial census the following year recorded as a member of the Yeslers' Seattle household a "Julia Benson age 15, female, race - HB (half breed), house servant, born in Wash. Terr." ("Henry Yesler's Native American daughter ... ").

Julia later would marry a white man, Charles Intermela, with whom she would have two children. She became the only known child of Henry Yesler to survive into adulthood. Back in Ohio, son George was dead within a year of Sarah's departure, falling prey to a virulent but unidentified disease. His death seems to have ended the Yeslers' plans to return to Ohio, and they turned their energies to developing the still-struggling little town that would now be their home for life.

An Unconventional Couple

Yesler's infidelity would have tested most marriages, but appears to have had no effect on Sarah's deep and loving bond with her husband. Her acceptance of his behavior may have been due in part to the non-traditional beliefs they shared. The Yeslers were freethinkers, unaffiliated with any organized church. A long-standing interest in spiritualism only increased after their son's death, and the couple nurtured hopes of contacting him through the intercession of mediums and others claiming special powers. Many of these questionable seers also advocated free love in lieu of traditional marriage.

For his part, Henry Yesler proved equally tolerant of Sarah's relationships with other women, at least two of which, judging from correspondence, were intimate and of some duration. Sarah fought depression most of her life, exacerbated by the death of her son, and on occasion left Seattle to take questionable cures in sophisticated San Francisco. Her extended absences gave rise to whispers of more infidelities, but left her husband unbothered. The Yeslers made no efforts to hide their unconventional beliefs, much less apologize for them, and the Reverend Daniel Bagley (1818-1905) was known to include a prayer for the "God-forsaken couple" during Sunday services at the city's Methodist church (Women in Waiting, 171).

The Yeslers' open-handed hospitality and involvement with spiritualism gave them a connection to literary fame, although they would not live to know it. In the 1870s, they hosted sessions at their home led by William Henry Chaney (1821-1903), an itinerant spiritualist, astrologer, free-love advocate, charlatan, and all-around cad. Flora Wellman (1843-1922), a friend from back in Massillon and a fellow spiritualist, had left Ohio after a family fight and was taken in by Henry and Sarah in Seattle. There she met Chaney, was infatuated, and followed him to San Francisco, where she became pregnant and was soon abandoned by him. After giving birth to a son, Flora met and married a widower, John London, and gave the boy his name. In later years, this boy would be known worldwide as Jack London, one of America's leading authors, journalists, and social activists.

Diversification

When King County was established by the Oregon Territorial Legislature in December 1852, just two months after his arrival in Seattle, Henry Yesler was appointed county auditor, not for any particular skills or interests he may have had, but because there was barely a handful of qualified men in Seattle, the county seat. It was not the last office Yesler would hold in local government (he was twice mayor of Seattle), but he was not a man deeply involved in politics, except when necessary to advance or protect his business interests. It was to those interests that he and Sarah devoted their attention after her arrival in Seattle in July 1858.

In 1859 Henry, with Sarah's support and encouragement, began to develop his downtown property, building Yesler Hall at the corner of Commercial Street (which became 1st Avenue S) and Mill Street (Yesler Way). It held a general store, a theater, and a community meeting hall. With financial contributions from Seattle residents, Yesler built a third public space (after the cookhouse and Yesler Hall) for the July 4th celebration in 1865, this one called Yesler Pavilion. The following year, the original cookhouse, the last survivor of the town's first log buildings, was razed, and in 1870 Yesler Pavilion was renovated to become the new Yesler Hall. It too would be a center of the city's cultural life and would host everything from minstrel shows to Shakespearean drama and grand opera. But Seattle was still a frontier town; women patrons in long dresses had to pick their way across floors spit-slickened by the men's near-universal habit of chewing tobacco.

Yesler's business dealings over the years were many and varied and ranged from disastrous informality to mystifying complexity. In the late 1850s and early 1860s he took on a total of eight different business partners in the operation of what was called the Seattle Mill Company, both locals like Arthur Denny and investors from California. These relationships were invariably fraught, and by 1866 Yesler had worn out or bought out all but one partner. George Plummer, a wealthy sea captain from San Francisco who had invested heavily in Yesler's enterprises, was the last man standing.

One of Plummer's roles was to purchase supplies in California to be shipped north for sale in the Yesler store. To Plummer's dismay, Yesler freely, even recklessly, gave customers credit, usually asking for no security in return. This left the store chronically short of both cash and inventory. Plummer responded by refusing to provide additional supplies, forcing Yesler to buy goods from the store of another early settler, Dexter Horton (1825-1904). He then had to sell for higher prices than Horton was charging, which was not a recipe for success. Yesler's store never turned a profit, even though Sarah nagged her husband to require cash at the time of sale (even buying an ad in the local paper to announce the new policy) and made frequent trips south to placate Plummer. Finally, in the summer of 1868 and to the great relief of both, Yesler was able to buy out Plummer's interests in return for 350,000 board feet of lumber.

By this time, and despite some upgrades, the limitations of Yesler's original mill made it barely worth operating. Backed by $17,000 in loans from the loyal John McClain, in 1868 Yesler began building a new and greatly improved sawmill just west of the original. By March 1869 it was ready to begin production, with about twice the capacity of the first one and the ability to produce fully finished lumber. The old mill was then demolished to make room for the development of some of the town's early commercial buildings, its aged equipment having been converted to use in a grist mill Yesler started in another largely unsuccessful venture.

Yesler's dealings during this period extended far beyond the mill and the store. His first crude water system was gradually improved, and in 1865 Yesler and fellow pioneer Charles C. Terry (1828-1867) started the Seattle Water Company. It drew water from a spring near Third Street, carrying it through hollowed logs to what then passed for "downtown." Terry died two years later, but Yesler continued on, eventually supplying water to many of the town's commercial buildings. He would keep his interest until the mid 1880s, when he sold out to the Spring Hill Water Company for $4,500. In 1869, Yesler also invested in an enterprise to provide gas for lighting, and although this failed, a similar investment made later was worth almost $100,000 by the time he died.

Over a span of more than 15 years, Yesler also devoted significant time, energy, and expense trying to make money from coal, but was repeatedly foiled by the difficulty of getting it from the mines east of Seattle to Elliott Bay. Finally, in 1871, a complicated route from the far shore of Lake Washington was in place that involved barges, trams, and a portage across what is now the Montlake Cut. Coal had to be laboriously transferred from one form of transport to another no less than eight times on its journey, and the cost of getting it to market pretty much guaranteed little or no profit. Yesler would continue to dabble in coal until 1876, but there is no evidence that he ever made a penny from it. Eventually, it would be California investors who would profit, greatly helped by the extension of the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad to the mines in 1878.

Desperate Times

Henry Yesler's business ethics were probably no better or worse than those of most men striving to make their fortunes in the West, and the trail of his various investments, partnerships, arguments, break-ups, and lawsuits is long and twisting. It's impossible to judge the merits of many of the claims made against him, or made by him against others, but one thing is certain: No matter how aggrieved his various partners and creditors may have felt, Yesler did not become wealthy at their expense. In fact, by the end of the 1860s, and despite a new mill and a booming lumber market, he was deeply in debt from wanton borrowing. It was fortunate that his old friend McClain held many of the notes against him, but debt was debt, and in 1871 the country's leading credit agency warned that Yesler was in a "hampered condition" and too indebted to be considered "safe" ("Henry Yesler's 'Grand Lottery ... '").

The Yeslers still owned most of the property he had claimed in 1852 but, although it was increasing in value, there were few buyers. In the summer of 1871, Yesler offered to sell much of his waterfront holdings, including the new mill, to McClain and another creditor from Ohio for $65,000, but was rebuffed. Things just got worse from there. He leased out the mill in 1872 for a mere $350 a month, but as the middle of the decade approached, many of his notes were coming due. By 1875, at the end of Yesler's first one-year term as Seattle's mayor, what little income he had from rents was barely adequate to service the interest payments on his debts, much less pay off the principal. Something had to be done, and, with pioneer boldness, Yesler set about to do it.

The Grand Lottery

Yesler's plan was to liquidate much of his property, including the sawmill, by holding a lottery. Since that was illegal under the laws then in effect, he lobbied the territorial legislature to enact a new law that would permit it, promising in return that 10 percent of the proceeds would be earmarked for the territorial university and other public schools. The legislature responded favorably, but decided that the 10 percent should be used to finance construction of a wagon road over Snoqualmie Pass, something settlers on both sides of the Cascades, including Yesler, had been trying to achieve for years. The title of the new law was "An Act to Aid in the Construction of a Wagon Road across the Cascade Mountains," but many shared the opinion that it was more an act to extricate an old pioneer from the consequences of his own improvidence. The statute, which never used the word "lottery," began:

"Be it enacted ... That any person residing in this territory, who is desirous of aiding in the construction of a wagon road across the Cascade Mountains, shall have the right to dispose of any property, real and personal, situate in this territory, by lot or distribution, under such restrictions and conditions as are provided in this act'' (Wash. Terr. Laws, 1875, p. 180)

The ink was barely dry when Yesler ordered tickets from Clarence Bagley (1843-1942), then the official territorial printer in Olympia. He started advertising "The First Grand Lottery of Washington Territory," offering single tickets for $5, or 11 for $50, with 60,000 tickets to be sold and the drawing to be held on the nation's centennial day, July 4, 1876. First prize was the mill and the land it sat on, valued (in Yesler's rosy estimation) at $100,000. Second prize was one of his commercial lots, at the corner of what is today Yesler Way and First Avenue South. There were 5,573 other prizes promised, including 4,500 cash awards and hundreds of lots scattered around Seattle, many from the Yeslers' original claim, but 470 of which he bought from others specifically for the lottery, paid for in part with lottery tickets.

It was an audacious plan, but it was doomed. The hope of selling 60,000 tickets seemed slim in a county with a population of only about 3,500 people and a huge territory with barely 50,000 widely scattered, non-Native men, women, and children. Other hopeful lottery operators drained away many potential customers and sharpened the opposition of anti-gambling forces (which included many who ran illicit gambling activities of their own) that may have tolerated a single one to benefit an old pioneer. Two weeks before the scheduled drawing, Yesler announced that it would be delayed until January 1877. Shortly thereafter, those opposed to the lotteries filed suit, and a King County judge ruled that the statute permitting them was counter to federal legislation governing territories and thus void, and that those running them were therefore violating the criminal laws. Several, including Yesler, were charged by a grand jury, but he was treated leniently, let off with a $25 fine and court costs.

Oddly, there was very little follow-up, either by authorities or the press. The legislature found it necessary in 1877 to pass "An Act to Provide for the Recovery of Certain Money Raised to Aid in the Construction of a Wagon Road Across the Cascade Mountains." It authorized the King County auditor to demand that any and all lottery money raised be paid into the public treasury. There is no indication that any money was recovered, and on the basis of all available evidence, it appears that Yesler personally profited little, if at all. Forty years after the fact, one history of Western Washington alleged that approximately $30,000 "said to have been collected from the sale of tickets was not accounted for" ("Henry Yesler's 'Grand Lottery ... '"). But Clarence Bagley, who had printed Yesler's lottery tickets and went on to become a popular historian, elided the question of Yesler's conduct in his 1916 account: "The affair was soon forgotten and if there were any dark spots in the history they were covered up and allowed to hide themselves from sight" (Bagley, 219).

Rich Man, Poor Man, Rich Man

Yesler's reputation seems to have been not much changed by the fiasco. Those who already thought him a rogue believed their suspicions confirmed; those who believed him in large part responsible for the city's progress were happy to let the matter simply fade away. Yesler's properties, most of which he would have surrendered had the lottery been held, eventually became worth far more than the $300,000 he'd hoped to raise. He and Sarah sold many of their residential lots on First Hill and began to develop those in the commercial center of town in earnest, putting up multiple buildings of both brick and wood.

By 1881, the couple was enjoying a handsome income from commercial rentals. They began construction of a grand mansion in 1883, the same year Henry started work on his third sawmill, this one on the north side of his downtown wharf. But fate seemed determined to make things difficult for the Yeslers. The national economic depression that hit later that same year almost ruined them; they were unable to finish their lavish new home, and when they finally took up residence in 1886 they found it necessary to rent out many of its rooms as unfurnished office spaces. In the meantime, in 1885 Yesler was elected Seattle's mayor for a second one-year term, during which he opposed attempts by townspeople to violently evict the city's Chinese residents.

By the time that mayoral term ended, many believe Henry Yesler had slipped into mild senility. His tangled business affairs had become only more so -- he had continued to both borrow and lend money with abandon, regularly obligated himself as cosigner on notes for friends with poor credit, and allowed tenants to skip rental payments without consequence. Having lived through so much, Yesler alone seemed unconcerned, but his many creditors were not nearly so sanguine. Things finally came to a head in March 1886, when the Yeslers agreed to transfer all their property in trust to James D. Lowman (1856-1947), Henry's nephew from Leitersburg, who had come to Seattle in 1877. From that point on, Lowman would help Yesler manage his affairs and is widely credited with straightening out and securing his sizable fortune.

Tragedy struck when Sarah died suddenly on August 28, 1887, at the age of 65. As if Yesler hadn't enough problems, her estate was contested by her relatives, and a long legal battle ensued, with Henry largely prevailing after nearly five years of litigation. Shortly after her death, he and Lowman embarked on a long trip to the East, during which they borrowed $250,000 from the German Savings and Loan Society in Chicago, which they used to retire most of Yesler's other debts. Then, less than two years later, on June 6, 1889, the Great Seattle Fire destroyed most of Yesler's downtown commercial buildings. In a day, his rental income of about $60,000 a year dropped to virtually nothing. But, assisted by Lowman, the old man bounced back once again, replacing much of what was lost with fine buildings of brick and stone, some of which, most notably the Pioneer Building, survived into the twenty-first century.

One Last Surprise

On the trip east with Lowman, Yesler visited many members of his extended family whom he had never met. One of these was Minnie Gagle (1868-1973), the daughter of a cousin on his mother's side. She and her mother moved to Seattle in 1888, and soon Minnie was old Henry's constant companion. The three traveled to Maryland in August 1890, and when they returned it was announced that Minnie and Henry had married while visiting Philadelphia. He was nearly 80; she was in her early 20s. Her motives (and those of her mother) were of course widely questioned, but Henry, as always, remained unconcerned, and it seems that his new wife devoted herself to his comfort and ease.

In 1892 Henry and Minnie traveled to Alaska and Yellowstone Park, and he seemed hale and hearty for his years, although his mental faculties were clearly affected by age. After their return Yesler took ill, and died early on the morning of December 16. Thousands of mourners from all walks of life paraded through his huge home.

Predictably, the settlement of Henry Yesler's estate was an imbroglio of epic proportions. It pitted Minnie Gagle Yesler and her mother against James Lowman and municipal authorities, who believed that Yesler had made a will that left most of his fortune, by then worth more than $1,000,000, to the city, hoping thereby to cement his reputation as the "Father of Seattle." No will was to be found, and Lowman was able to have criminal charges brought against Minnie Yesler, alleging that she had hidden or destroyed it. Those charges were eventually dropped, and whether such a will ever existed remains unknown. Minnie Yesler was supported by the estate for several years, and she lived in the mansion until 1899, when it became home to the Seattle Public Library. Having survived the Great Fire of 1889, it was destroyed by flames on New Year's Day 1901.

Minnie disappeared from local view, leaving vacant a spot reserved for her in the city's Lakeview Cemetery next to the graves of Henry and Sarah. As late as the 1930 federal census, she and her mother were known to be living in Los Angeles, and official records indicate that she died there in 1973, when she would have been about 105.

Legacy

On the day of Henry Yesler's death, one of his longtime friends said with some sadness:

"Death came just as he was completing his object in life. His wealth he has never had a chance to enjoy, as he was taken up with business cares. This coming year he had intended to settle back and enjoy life. He put off that pleasure too long" ("Henry L. Yesler's Seattle Years," 365).

For a man with little formal education and a demonstrated lack of money-management skills, Henry Yesler accomplished much. Although he spent much of his life in Seattle deeply in debt, hounded by creditors and harried by disillusioned partners, he ultimately left a legacy few could match. There no doubt would have been a Seattle without Henry Yesler, but its development into the leading city of the Pacific Northwest might well have been delayed or not achieved at all. Had Yesler decided to build his first mill in Olympia, Tacoma, or anywhere on Puget Sound other than where he did, the region's history may have turned out very differently.