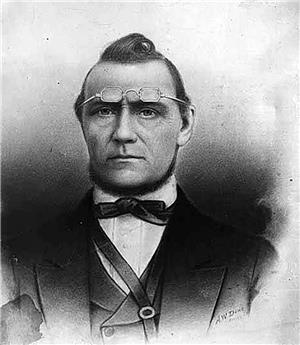

David S. "Doc" Maynard was a colorful and influential figure in King County's early history. Historian Bill Speidel anointed him "The Man Who Invented Seattle." On the advice of Chief Seattle, Maynard settled in the tiny village of Duwamps (Seattle’s original name) in the spring of 1852 and served as its first physician, merchant, Indian agent, and justice of the peace.

The pioneers renamed the town to honor Chief Seattle at Maynard's urging, but Maynard often clashed with more conservative (and sober) settlers such as Arthur Denny. Maynard lost confidence in the village after the Indian Wars of 1856 and traded his claim to much of present-day Pioneer Square for farm acreage in West Seattle. His property later became entangled in a complicated dispute between his first wife, Lydia Maynard, and his second wife, Catherine Broshears Maynard. Maynard remained in the area until his death in 1873.

Maynard was born in Vermont on March 22, 1808. He enjoyed a successful career as a medical doctor and operator of a medical school in Ohio until the financial panic of 1837 swept everything away. After doing his best to repay debt, Maynard said goodbye to his wife Lydia and to his two children, and joined the migration to California in search of a new life.

While administering to migrants stricken with cholera near Fort Kearney on the Platte River in Old Nebraska, Maynard's life took a fateful turn. As a doctor he cared for the William Broshears family. Israel Broshears died on the trail, leaving his frightened widow, Catherine. Maynard agreed to accompany Mrs. Broshears and her party to Tumwater, Oregon Territory, at the southern tip of Puget Sound, where Catherine's brother, early Sound pioneer, Michael T. Simmons, was waiting for her.

Somewhere along the trail Doc and the widow Broshears fell in love. When they arrived on Puget Sound, Doc took a long look at the beautiful surroundings, a second look at the widow, and forgot about California.

Doc Maynard settled in the hamlet of Smithter, later called Olympia, and began cutting and stacking cordwood. He sold the wood in San Francisco for more than $2000, and then invested this small fortune in trading goods from a wrecked ship. He opened a store.

Murray Morgan, in Skid Road, writes that Maynard:

"... purchased his goods at half price, (and) sold them at half the price asked by other merchants. If he was feeling particularly good — and alcohol often made him feel particularly good — he was inclined to give his customers presents: he offered unlimited credit. Maynard was popular with the townsfolk but not with other merchants ... ."

After hearing of opportunities near Elliott Bay, Maynard closed his failing business and climbed aboard a canoe owned and paddled by Chief Seattle and other Duwamish Indians. On March 31, 1852, Doc Maynard stepped onto the beach at the five-month-old settlement of New York-Alki.

Four of the Alki pioneers had already made plans to move across the bay, which seemed to offer better prospects. Maynard joined William Bell, Arthur and David Denny, and Carson Boren and their families at the new site on Elliott Bay.

Doc Maynard hired Indians to help him build a cabin on the "Sag," or lowlands (present-day Pioneer Square, near present day Yesler Way). Maynard built his cabin on what is now the northwest corner of First Avenue South and Main Street, near the water.

Almost immediately he undertook several enterprises. With the aid of Indians he cut cordwood, caught and salted salmon, and manufactured barrels. According to an ad he put in the Olympia Columbian, his "Seattle Exchange" sold "a general assortment of dry goods, groceries, hardware, etc., suitable for the wants of immigrants just arriving."

When Henry L. Yesler stepped ashore at Seattle to assay the potential of a steam sawmill, Doc Maynard extended his hand to the bearded visitor and began his real estate sales pitch. Carson Boren and Maynard shifted the corner of their claim stakes to accommodate an area in the "Sag" for Yesler's steam mill, the first on Puget Sound.

Doc Maynard became a roving Chamber of Commerce on behalf of Seattle, preaching its virtues from Olympia to Port Townsend. Ever alert for talent, he sought blacksmiths, sea captains, missionaries, and settler families. He served as a delegate to the Monticello Convention, a semi-formal congress of northern citizens who sought to divide Oregon Territory and create a new territory north of the Columbia River.

He continued to court Catherine Broshears on trips to Olympia. In pursuit of the widow he lobbied the Oregon Territorial Legislature to pass an act that would give him a divorce from his wife Lydia. The legislature responded favorably and Catherine and David became man and wife on January 15, 1853 -- or did they? The land commissioner, who had received Maynard's sworn statement that Lydia was no longer his wife, assumed that Lydia had died. Meanwhile, the laws had changed, leaving the very much alive Lydia as co-owner of Maynard's property.

Following the creation of King County in late 1852, Maynard took office as its first Justice of the Peace, giving him the authority to decide small legal issues and officiate at marriages. He issued the County's first marriage certificate to David Denny and Louisa Boren and presided at their wedding on January 23, 1853.

In early 1853, Arthur A. Denny, Carson Boren, and Doc Maynard decided to plat their adjacent holdings for a new Seattle township, but they could not agree on how to orient their respective street grids. Maynard insisted on strict adherence to the compass for his relatively level -- and soggy -- holdings south of Mill Street (Yesler Way) in present-day Pioneer Square. Denny later wrote that Maynard, "stimulated" on liquor, had decided, "he was not only monarch of all he surveyed, but what Boren and I surveyed too." Unable to agree, the neighbors filed two separate plats on May 23, 1853, and their dispute is memorialized today in the tangle of mismatched cross-streets along Yesler Way.

Perhaps one of Doc Maynard's most enduring qualities, besides his amiability, was his high regard for the local Indians. Chief Seattle was a particular friend, having stated: "My heart is very good toward Dr. Maynard." Maynard, who knew tribulations in his own life, understood that besides the tools, medicines, guns, and other wonders that the white men had brought to Puget Sound, they also introduced disease, intolerant religions, and the inhospitable idea of private property.

After Washington achieved Territorial status in March 1853, Doc Maynard was appointed Indian agent for the Seattle area. He took his duties seriously, listening to complaints, giving out medicine, delivering babies, lancing infections, and setting broken bones. The new Territorial governor, Isaac I. Stevens, held his first conference with Seattle-area Indians in front of Maynard's store in 1854. Several months later Maynard helped arrange the treaty conference that was held at Point Elliott (Mukilteo) to decide the fate of Indians living along the northern shores of Puget Sound. Despite Maynard's best intentions, this and other treaties led to misunderstandings and eventual violent conflicts between whites and Indians, including the "Battle of Seattle" on January 26, 1856.

In 1857, disillusioned by pre-Civil War passions (Maynard was a Democrat surrounded by proto-Republicans) and Indian conflicts, Doc Maynard traded his 260 acres of "downtown" Seattle for a 319-acre farm at Alki Point owned by Charles C. Terry. Maynard turned out to be a poor farmer. After their farmhouse burned to the ground, he and Catherine returned to Seattle to open a two-room hospital on the (1990s) site of the Elliott Bay Book Co. in present-day Pioneer Square. Maynard half-heartedly practiced law, having been admitted to the bar by an 1856 act of the Washington Territorial Legislature. His fortunes deteriorated with the arrival in Seattle of the first Mrs. Maynard, the abandoned Lydia, in search of her one-half ownership of Maynard's original donation claim. Lydia's claim was later disallowed because she had not lived on it. Catherine's right to the original property was also disallowed because she had not settled on it in time.

David S. "Doc" Maynard died on March 13, 1873. His funeral was the largest Seattle had known. One of his fellow citizens, speaking at the service, said, "Without him, Seattle will not be the same. Without him, Seattle would not have been the same. Indeed, without him, Seattle might not be."