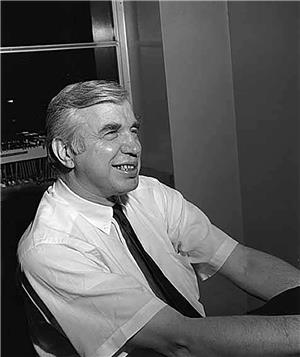

Emmett Watson was a fixture in Seattle journalism for more than half a century, first as a sports writer for the Seattle Star and then as a columnist for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times. Adopted following his mother's death shortly after his birth in 1918, Watson was raised by John and Elizabeth Watson, of West Seattle. He initially pursued a career in baseball, but proved more successful describing games than playing them. He scored his first international scoop by revealing the suicide of author Ernest Hemingway in 1961, and later entertained generations with his pithy commentaries on Seattle's changing social landscape. A paladin with a pen, Watson stood for Lesser Seattle against Greater Seattle, and delighted in puncturing the pomposities of local Babbits and self-appointed civic Boosters. He died of post-surgical complications on May 11, 2001.

From Home Plate to Sports Desk

Lena McWhirt gave birth to Emmett in Seattle on November 22, 1918. Both Emmett's mother and twin brother, Clement, perished in the following year's "Spanish Influenza" epidemic. His father Garfield, an unskilled laborer, could not cope with the needs of an infant and arranged for Emmett's adoption by John and Elizabeth Watson of West Seattle.

Emmett Watson enjoyed a normal childhood, but suffered an ear infection that permanently impaired his hearing. He attended high school first in West Seattle and then transferred to Franklin, where he met and played baseball with the legendary Fred Hutchinson before graduating in 1937.

Despite dismal grades, he talked his way into the University of Washington and donned a catcher's mask for the Huskies. He played well enough be tapped by Emil Sick's Rainiers, but saw few games in the Pacific Coast League. Watson caught the eye of Seattle Star editors when he produced a newsletter for enlisted baseball players, and he joined the paper in 1944. While there, he contracted polio, which left him with a permanent limp.

Three Dots and a Scoop

The Seattle Times hired him two years later (the Star did not survive much longer, but this does not suggest cause and effect). The P-I lured Watson away with higher pay and promise of a more creative editorial policy in 1950, and he made his home under the Globe for the next 30 years.

Sports -- and especially baseball -- was Watson's beat for the first years of P-I tenure, but more and more social commentary snuck under the fence of his columns. Editors gave him a wider field in 1956 with a "three-dot" item column called "This Our City." He scored a journalistic homerun when he reported that Ernest Hemingway (b.1899) had died of a self-inflicted shotgun wound in Ketchum, Idaho, on July 2, 1961 -- not by accident, as Hemingway's wife Mary initially stated.

As his popularity grew, so did the frequency of his columns until Watson was filling 20 inches as many as six times a week. Fortunately he was aided by a succession of savvy assistants, including Carol Barnard, Susan Gerrard, and Jean Godden (b. 1931), who sifted tips and suggestions from thousands of readers, informants, and would-be celebrities.

Battling Babbitry and Bigotry

Watson's gravelly voice would thunder through the gossip and chat-chat when a cause fired his blood, whether promoting a Seattle pro baseball franchise or denouncing Urban Renewal schemes to flatten Pioneer Square and sanitize the Pike Place Public Market. He was an early and stalwart champion of civil rights and social reform and befriended the anti-war movement and Counterculture. Famously, he stopped shaving to protest a P-I ban on staff beards in the 1960s; the prohibition was quickly repealed.

Watson's favorite targets were the self-righteous guardians of public morality and "progress." Playing on the name of an early group of tourism and growth boosters, Greater Seattle, Inc., he named himself press secretary of Lesser Seattle and delighted in skewering the business establishment's grand schemes for development and "civic improvement."

Although he usually dipped his pen in humor, not bile (except when writing of President Richard Nixon, whom he genuinely detested), Watson's irreverent skepticism made enemies. When he began nipping at the heels of former Seattle Mariner's owners George Argyros, P-I management yanked his leash.

Travels with Tiger

Watson quit in 1982 rather than compromise, and worked briefly as a publicist for self-help promoter Lou Tice and his Pacific Institute. He also took time to write and compile several books, including Digressions of a Native Son, Once Upon a Time in Seattle, and My Life in Print. He suffered a mild heart attack in the 1980s, which grounded his hobby as a pilot.

Watson returned to daily journalism in 1983 with a new weekly column at the Times. While social injustice could still rouse him to pound out the occasional manifesto against greed and arrogance, Watson generally maintained a mellower tone, reminiscing about earlier Seattle, honoring aging or departed personal heroes, and, most popularly, recounting his adventures with several incarnations of a miniature French poodle named Tiger. As much as he loved writing, Watson did not hesitate to join the picket line in November 2000, when the Newspaper Guild struck the Times and P-I. He never returned.

Virginia Mason physicians operated on Watson's burst abdominal aneurysm on March 21, 2001, but complications followed. He died on May 11, and was survived by Betty Lea, his former wife of 28 years, and daughters Lea Watson and Nancy Brasfield.