Licton Springs celebrates a long history as both a unique recreational spot and a commercial crossroads. The residential neighborhood in north Seattle is wedged between the busy corridors of Interstate-5 and Aurora Avenue. It takes its name from Liq'tid or Licton, the Salish word for the reddish mud of the springs -- one of the few Puget Sound Salish words still used as a place name.

Native Americans

The Aurora-Licton Springs area was once heavily forested, and filled with numerous mineral springs, bogs, and marshes. The Duwamish tribe called the group of springs Liq’tid (LEEK-teed) meaning red, colored, or painted, from the red oxide that still bubbles up in Licton Springs Park. Cedar, Doug-fir, hemlock, alder, and willow trees abounded in the area along with ferns and salal. Every few years the Duwamish people set fires to hunt and to aid in cultivating wild plants.

The area had spiritual significance to the Duwamish people who built sweat lodges near the springs. They painted their faces with the reddish mud from the springs and used the colors to decorate longhouses with magical shamanistic images. Healers administered herbs and soothed aching bodies with the red mud.

There was a marsh approximately 85 acres in size west of the springs. The Native Americans called the marsh area Slo’q `qed (SLOQ-qed) or "bald head" and gathered cranberries there.

Settlement

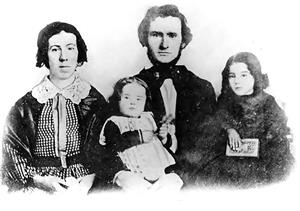

In 1870, Seattle pioneer David Denny (1832-1903) purchased 160 acres, including Licton Springs, from the U.S. government for $1.25 an acre. He built a summer cabin on the property. That same year, David's brother Arthur Denny (1822-1899) purchased 400 acres to the west. David Denny and his family spent time at their wilderness retreat at Licton Springs. In 1869, he shot the last elk in Seattle near Green Lake.

Denny had the water at Licton Springs tested in 1883 and it was determined to be healthful. There were at least two springs in the area: one with sulfur magnesia and another with iron, which caused the reddish color. Denny constructed a two-story frame house at Licton Springs and contemplated a health resort for invalids and pleasure seekers. Denny's daughter, Emily Inez Denny reportedly had an incurable disease and was restored to health by drinking the waters of Licton Springs.

After the Panic of 1893, David and Louisa (Boren) Denny (1821-1916) were forced to move from their home on Queen Anne Hill, first to a small house in Fremont, and finally to their summer cottage at Licton Springs. David Denny died there on November 25, 1903.

Development

Following her father’s death in 1903, Emily Inez Denny offered the 81-acre Licton Springs property to the city of Seattle for development as a public park. The city declined this offer. In 1909, Calhoun, Denny & Ewing acquired the site and platted it as Licton Springs Park.

The Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts, were retained by Calhoun, Denny & Ewing to draw up plans for a park. They proposed an organic layout with a park, rustic drives, paved streets, and home sites. The Olmsted plan, never fully realized, included rustic shelters over the two spring basins, bridges, paths, and clearing the reserve around the springs as well as preservation of the original, rustic Denny cabins. One remnant from the Olmsted plan for Licton Springs that exists today is a portion of the street network, where Woodlawn Avenue curves to connect with N 95th Street.

Calhoun, Denny & Ewing departed from the Olmsted plan and platted 600 building lots, but they retained Licton Springs as an open space reserve within the development. Licton Springs was a favorite picnic spot in the early years of the twentieth century, and its healing waters attracted attention.

The water from Licton Springs drained into Green Lake via Becker’s Creek. In 1920, Becker’s Creek and Licton Springs were enclosed in a buried pipe to Green Lake to protect the lake’s water supply. In 1931, the city of Seattle diverted water from the springs into storm drains because of pollution from septic systems (and presumably outhouses) in the area.

In 1935, Edward A. Jensen opened the only spa ever at Licton Springs, offering thermal baths that included 19 minerals. He bottled the water and sold it. Jensen died in 1951 before he realized his dream of a sanitarium. His widow, Mabel M. Jensen, sold the property to A. R. Patterson who planned a $500,000 sanitarium. The city purchased the 6.3-acre property in 1960 for use as a park. Since the bond issue did not include funds for development, the only improvements were the demolition of Jensen’s building, the spring shed at the iron spring, and the concrete ring at the large spring to the south.

The 1968 Forward Thrust bond issue provided funds for Licton Springs Park. Planners preserved the little remaining natural vegetation. The southern spring area became a small pond and was planted with wetland vegetation. Additional improvements, including planting of trees and replacement of the play structure, were made in 1987 using Seattle 1-2-3 bond funds. Reforestation and improvements such as interpretive signs have been made to the park in recent years with considerable volunteer assistance from the Licton Springs community.

Agriculture

Akira and Sayo Kumasaka had a greenhouse business where North Seattle Community College was built in 1968. There were a number of other Japanese families in the area, running greenhouses or small farms, and their children attended a Japanese language school at the corner of their property.

James Albert and Marietta Heiner Pilling brought their family to Licton Springs from Capitol Hill in 1909. The Pillings had 20 dairy cows, and they delivered milk as far as Lake Union. The Great Depression and the trend toward pasteurized milk forced the dairy to close in 1933. In 1931, James’ son, Chuck, began digging a pond near the creek. Chuck had long been fascinated by ducks and had been raising them since he was 12. Once he got out of high school, he turned to it more seriously, damming the creek and forming a pond to provide habitat for a variety of water fowl. In the 1970s, Chuck retired to pursue water fowl breeding on a full-time basis. His most notable accomplishments were as the first successful breeder of the hooded merganser duck in 1955, followed by the bufflehead (1964) and harlequin (1977) ducks.

Schools

In 1885, David Denny donated one acre of his property for a school. Oak Lake School, one room, 12 x 16 feet, was built with volunteer labor. It was located at the site of today’s Oak Tree Village. This was the only school in north King County at this time. In 1944, the Shoreline School District incorporated all schools north of 85th Street. The Oak Lake School closed in June 1982 and only the pedestrian walkway over Aurora remains as a reminder of the Oak Lake School.

The Interurban

For decades, Licton Springs was accessible only by horse and wagon. Eventually, streetcar lines reached Green Lake and north along Greenwood Avenue, not far from Licton Springs. The arrival of the Seattle-Everett interurban line in 1906 brought convenient transportation and attracted early residents. The line allowed people to buy homes away from the city, yet get downtown easily for work or shopping. Those with small farm plots used the interurban to ship produce into town for sale.

The Everett and Interurban Railway Company was first organized in 1900 by Fred Sander. Progress was slow and it was not until 1906 that it got as far as Bitter Lake, serving Licton Springs. In 1908-1909, Stone & Webster, owner of the firm (Seattle Electric Company) that ran the streetcars within the city, acquired the line. The interurban became the Seattle-Everett Traction Company and later, the Pacific Northwest Traction Co.

The Seattle-Everett Traction Company soon connected directly into downtown Seattle, down Greenwood and Phinney avenues, through Fremont, and on along Westlake and Fifth avenues. This new route avoided the transfer in Ballard, saving 30 minutes. On May 2, 1910, through service from Everett to downtown Seattle began, with a train every hour from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. The 29-mile trip, took about 95 minutes at first and was later reduced to about 70 minutes.

The trolleys became a part of everyday life, running on a narrow right-of-way through backyards, with the whistle adding to the neighborhood’s atmosphere. In the early years, the line ran through a semi-wilderness, dotted with chicken and berry farms. Several sawmills along the way gave the line a substantial business hauling lumber.

As early as 1915, the Pacific Northwest Traction Company itself offered bus service from Seattle to Bothell. Throughout the 1920s, cars and buses increasingly competed with the interurban. The completion of the Aurora Bridge in 1932 meant that buses could use Pacific Highway (Aurora) to reach downtown, giving them a considerable speed advantage over the trains.

The last car ran on the Seattle-Everett line on February 21, 1939. In 2001, the right-of-way was a transmission corridor for Seattle City Light power lines. The right-of-way will be developed as a walking and biking trail, connecting to the existing trail through Snohomish County.

Aurora Avenue N

Aurora Avenue N began as a rough wagon road through the forest, which came to be known as the North Trunk Road. In 1901, it became the R. F. Morrow Road. In the early 1930s, the entire street became Aurora Avenue N. The state identified it as Pacific Highway 1, and until 1969, it was U.S. Highway 99. In 1947, the route was selected as a Blue Star Memorial Highway to honor of World War II veterans. City Engineer (later mayor) George Cotterill (1865-1958) chose the name early in the twentieth century to recognize it as the highway to the north, toward the aurora borealis.

In 1911, Firlands Sanatorium for tuberculosis patients was established near the county line and a better road was needed to make it more accessible for staff and visitors. Aurora was eventually extended north of the county line, making a more direct route to Everett than the old Bothell-Everett Highway (Lake City Way NE). In 1913, much of the road was paved with bricks. The bricks were replaced with asphalt in 1928.

The George Washington Memorial Bridge over the Lake Washington Ship Canal opened in 1932, offering a quick, direct auto route from North Seattle to downtown. The opening of the highway had an immediate impact on Aurora Avenue through the Licton Springs neighborhood. Gas stations and auto repair shops of all descriptions were among the first auto-related businesses to open, beginning in the 1920s.

The most distinctive feature of the early auto era was the motel. Lodgings targeting motorists were originally called "tourist camps," "auto camps," and, later, "auto courts." One of the first was built by the Seattle Parks Department in Woodland Park in 1921. For $.50 a night, a car full of travelers could get hot showers, laundry facilities, and a telephone, and enjoy the community building overlooking Green Lake, with its veranda and open-air fireplace. Each night, local talent, amateur and professional, provided concerts, dances, movies, or other entertainment. By 1928, however, use decreased and the site was converted to tennis courts and a bowling green. The area around Licton Springs was annexed to the City of Seattle on January 1, 1954.

Post World War II

The Northgate Shopping Center (1950) and Interstate 5 (1967) combined to encourage further development and many apartments and office buildings were built on both sides of the freeway and along Northgate Way. The freeway supplanted Aurora as the major through route, and many Aurora businesses declined.

North Seattle Community College opened in 1970. The 66-acre, five-building campus cost $23 million. By 1972, enrollment was 5,000, the equivalent of 3,000 full-time students. In 2001, enrollment was more than 9,000 students.

Necropolis

Denny Park in Seattle was formed in 1884 on a cemetery deeded to the city by David and Louisa Denny. The remains and headstones were removed. One of those buried in Park cemetery was David and Louisa Denny’s son Jonathan, who died a few hours after he was born in 1867. Denny chose a plot at Oak Lake near his wilderness retreat at Licton Springs to rebury his son and as a family plot. Henry Levi Denny, David’s cousin, moved his family plot to Oak Lake in 1887. In 1891, David and Louisa Denny formally filed a plat of approximately 40 acres as Oak Lake Cemetery. David Denny envisioned Oak Lake as a cemetery for all races, and all walks of life, rich and poor.

In 1913, the Oak Lake Cemetery was purchased by American Necropolis Corporation and renamed Washelli. The first Washelli Cemetery in Seattle was located on Capitol Hill in 1884. The name "Washelli" was derived from a Makah word meaning west wind.

In 1920, the Evergreen Cemetery Company of Seattle, began clearing land across the North Trunk Highway from Washelli. Evergreen was planned as a "park" cemetery, which did not allow any upright monuments. Evergreen purchased Washelli in 1922. In 1953, Evergreen Washelli was one of the first cemeteries in the U.S. to build outside or garden mausoleums.