During the 1950s and 1960s, Charles O. "Chuck" Carroll was, arguably, the most powerful man in Seattle and King County. As King County Prosecutor he was the effective head of all law enforcement in the county and in complete control of who would or would not be prosecuted for crimes. He was also head of the Republican Party in King County and in a position to approve or disapprove political appointments and candidacies. The exposure of a police-payoff system in Seattle in the late 1960s generated allegations that he was responsible for the corruption. These questions led directly to his defeat in the primary election in 1970 and to his departure from public life.

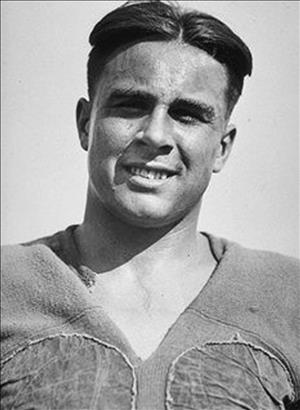

"Chuck" Carroll was born in 1906 to Thomas J. Carroll and his wife. Thomas Carroll was founder of Carroll's Fine Jewelry in 1895. The younger Carroll attended Garfield High School and the University of Washington. He played Husky football for coach Enoch "Baggie" Bagshaw (d. 1930) in the 1920s and achieved a phenomenal record as an All-American running back for passing, punting, and tackling. In those days, players wore leather helmets and the same 11-man team served as both offense and defense. Carroll's number 2 is one of only three Husky numbers to be retired. He was named to the College Football Hall of Fame and was a charter member of the Husky Hall of Fame.

After graduation, Carroll attended the University of Washington School of Law and he became a Seattle attorney. During World War II, he served in the U.S. Army in the Advocate General Corps.

Prosecuting Attorney

In 1948, the King County Prosecutor resigned to become a judge and the three County Commissioners chose Carroll to fill the vacancy. Carroll announced an investigation into rumors of illegal gambling in Seattle and King County. The Prosecuting Attorney set the policies that guided local law enforcement agencies. Carroll was in a position to push police to crack down on gambling and prostitution. Both were prohibited by state law, but they flourished nevertheless. The Seattle City Council passed an ordinance providing for the licensing of card rooms in 1953. This policy of tolerance allowed some police to develop an extensive system of graft in the city.

Carroll's influence grew in the Republican Party to the point that he could approve or disapprove all political appointments. If a judge stepped down, the opening was filled by appointment. The appointee enjoyed the incumbent's advantage at the next election.

Carroll probably reached the height of his power in 1957 when he prosecuted Teamster leader Dave Beck for grand larceny. Beck had a large influence on the economy of Seattle and the Northwest for decades. Beck did not report for his prison term for five years, but the case showed that Carroll was afraid of no one.

Seattle -- The Clean City

Business and political leaders in Seattle enjoyed the feeling that Seattle was free from traditional organized crime and they credited Carroll's tough stance on crime with keeping the city clean. Seattle Times political writer Ross Cunningham was a friend of Carroll's and The Times ran many positive stories about prosecutor.

Those who opposed Carroll might find themselves investigated and even prosecuted. King County Commissioner (later King County Executive and Governor) John Spellman admitted that he worried about being investigated and prosecuted for minor infractions of law.

Beginning in 1967, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and later The Seattle Times began to run stories about the police payoff system. Carroll was found to be meeting quietly with the owner of the company that operated pinball machines in the county. When Carroll learned of a planned article in Seattle magazine that would expose corruption, he threatened a lawsuit. The magazine still demanded his removal.

A Federal Grand Jury investigated as part of a Nixon Administration crackdown on crime. That inquiry resulted in the indictment of an assistant chief of police for perjury and his 1970 trial became a showcase for the scandal. Carroll was not directly implicated, but in the primary election of 1970, Republican Christopher Bayley defeated Carroll for the nomination.

Once in office, Bayley launched his own investigation. In July 1971, Carroll and 18 others were indicted for "conspiracy against government entities." Carroll's case was thrown out at trial, but the damage was done. Carroll left the public scene for good. He entered private practice and retired in 1985. In 1986, Carroll told journalist Don Duncan of The Seattle Times that he never condoned the "tolerance policy" that allowed small stakes gambling:

"I said bring me the facts for a case (abuse of the system) and I'll file it. I always worried that there might be payoffs to permit the stakes to go higher and higher. And that's what happened. The names of some good people were dragged through the mud."

According to a Seattle Times obituary, Carroll enjoyed in his retirement the society of many political leaders including former Governors Albert Rosellini and John Spellman. He was acknowledged by many community organizations for his leadership.

Chuck Carroll passed away on June 23, 2003, at the age of 96.