Issaquah, located east of Lake Washington along Interstate-90, has experienced two periods of rapid growth during its lengthy history. The first came in the late nineteenth century when the local economy was fueled by the coal, lumber, hop growing, and dairy industries. During the mid-twentieth century the town became somewhat dormant, then once again saw vast development. In 2003, the city was listed as the fastest growing community in the state of Washington.

A Change of Worlds

Native Americans inhabited Squak Valley for centuries before the arrival of noln-Indian settlers. When the first homesteaders arrived in the 1860s, relations with the Snoqualmie and Sammamish tribe were mostly peaceable. Mary Louie, an elderly Indian woman, was a friend to many early pioneers and taught their children some of the customs of her people.

The homesteaders named the valley Squak, their pronunciation of the local Indian name Is-qu-ah, meaning snake, although others say that the name meant "little stream," or possibly the sound of the northern crane, a bird common to the valley. The land was fertile, perfect for hops and other crops.

Local Indians were hired to help on the farms, but in one instance the mix of cultures created problems. In 1864, during Indian unrest throughout Puget Sound, William and Abigail Casto were killed by two Snohomish Indians in their employ. Also killed was John Halstead, a housemate. Another Indian in the camp ended up killing the assailants, but many people living in the valley fled to Seattle nevertheless.

Racial Unrest

Besides the rich farmland in the valley, the mountains surrounding Squak contained abundant deposits of coal. This was discovered in 1862, but it wasn’t until the arrival of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad in 1887 that coal mining became profitable.

Until that time, hop farming was the main industry for Squak Valley residents. By the 1880s, unrest with Native Americans had dwindled, and many Indians worked next to whites out in the fields. In 1885, the Wold brothers brought in 37 Chinese men to pick hops at a cheaper price. White and Indian hop pickers demanded that they leave. When the Chinese didn’t, the other workers snuck into their camp and murdered three of them.

The rest of the Chinese workers quickly left. Arrests were made, but the murderers were acquitted. Justice of the Peace George Tibbetts (b. 1845) was also charged as an accessory, when he refused to help in the protection of the Chinese on their way to the Wold farm. Nothing came of these charges.

Coal and Lumber

When the railroad arrived in 1887, coal mining began in earnest, and the little valley community experienced rapid growth. Hundreds of men, many of them immigrants, moved to the area looking for work. Conditions in the mine were harsh, but in time, many of the miners had saved up enough money to send for their wives and families.

For men who didn’t want to work underground, plenty of jobs were available at numerous lumber camps. With so many people moving to the valley, businesses were established. George Tibbetts became the town’s first entrepreneur, opening a store, a hotel, and a stage line.

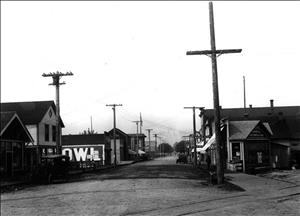

The town was platted in 1888, and incorporated under the name Gilman in 1892. The townsfolk must have liked the name Squak, as they renamed the village to Issaquah -- a closer approximation of the original Indian name -- in 1899.

Boom Town

In the 1890s, hop aphids destroyed much of the crop throughout Washington, but Issaquah had another agricultural industry to rely on. Sawmill and lumber companies cleared many of the trees in the valley, exposing excellent pasture land. The Northwest Milk Condensing Co. (later Darigold) opened in 1909, and soon Issaquah became one of the largest suppliers of milk to Seattle.

Coal mining continued apace, and throughout the 1910s newer and larger mines were developed. One of them -- the Issaquah and Superior Coal Mine -- was financed by German investors, but soon ran into money problems when support dried up at the beginning of World War I. Nevertheless, other mines prospered.

The logging industry also continued to grow, as did the city. As with any boomtown, hotels were everywhere, along with saloons, liquor stores, and tobacco shops. But the rough and tumble town was also being domesticated, and by 1920 citizens had telephones, indoor plumbing, schools, and banks.

Getting By

The coal industry started dying out in the 1920s, as fuel oil became a more popular resource for heating homes. When the Great Depression began in 1929, it hit the logging industry hard. Issaquah’s dairy farms were still prosperous, but the boomtown days were over. For the next 40 years, Issaquah saw little change in its population of approximately 900 persons.

During this time, the town may have been isolated, but long-time residents enjoyed life in their now sleepy community. Social organizations flourished, and many local citizens became involved in civic groups and community boosterism.

Memorial Field, which had been developed in 1918 by the volunteer fire department became home to the Issaquah Round-up, the annual rodeo. During the rest of the year, townsfolk would gather there for high school football and baseball games.

Many people worked where they could. In 1936, the federal Works Progress Administration provided jobs through the replacement of the town’s sewer system, and the construction of such buildings as the Sportsmen’s Club and the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. Many years later, graffiti was found under a board at the hatchery, bearing the date September 16, 1936, and reading "This was the way we had of existing thru happy days of capitalism."

Road to the Future

Sunset Highway was built through Issaquah in the 1920s, bringing the small town into the Auto Age. The opening of the Lake Washington Bridge in 1940 brought more people to the Eastside. Highway 10 (now Gilman Boulevard) opened in 1941, and Issaquah saw a minor growth spurt when work at the sawmills was needed for the war effort.

After World War II, many Seattle residents began migrating to Eastside suburbs, beginning with communities closest to the lake such as Bellevue, Kirkland, and Renton. In 1958, Issaquah’s train depot closed, but a few years later, work began on Interstate-90, connecting the town with Seattle to the west, and with points elsewhere to the east. Thus began the town’s second boom.

By 1970, the town’s population had more than quadrupled to 4,313 residents. Its coal mining days long over, the community saw an increase in gravel mining, needed in the construction of homes and roads. Real estate, which had remained stable for decades, soon became a hot prospect.

Although the city was beginning to change, efforts were made to capture and preserve much of its past. The Issaquah Historical Society was formed in 1972, when many old loggers and miners were still alive. Since then, the organization has gathered thousands of photographs, stories, and ephemera, and has also restored the old train depot and town hall into museums.

Boom Town, Redux

For most of its history, the town of Issaquah was nestled around its downtown. As more people moved to the valley, the city began annexing the surrounding area, including much of Cougar Mountain and Squak Mountain, as well as the Issaquah Highlands on the south end of the Sammamish Plateau.

Beginning in the 1980s, much of the farmland in the valley was sold to developers. Since then, the valley has filled with shopping centers, restaurants, and other businesses. Housing prices were affected accordingly, with the median value of homes topping $250,000 by the end of the century. This has caused traffic problems along the I-90 corridor, necessitating new interchanges and more lanes.

As at the beginning of the last century, Issaquah became a boomtown again. In 2003, census data revealed that Issaquah was the state’s fastest growing city.