Samuel Hill made the Northwest his home for a little more than 30 years, leaving a legacy of philanthropy, monuments, and highways still visible in the twenty-first century. He made a small fortune in utilities and investments and spent most of it on other people, on causes and programs he believed in, and in traveling the world to promote peaceful trade and prosperity. His most notable achievement was the establishment of the Maryhill Museum of Art overlooking the Columbia River near Goldendale, Washington.

From South to Far North

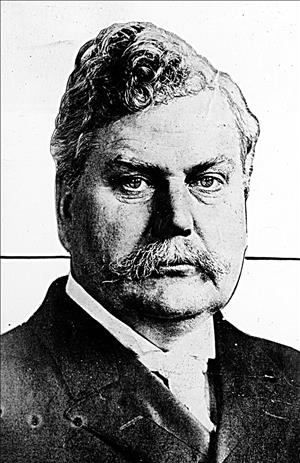

Samuel Hill was born to Quakers, an abolitionist physician and his wife, in North Carolina in 1857. At the end of the Civil War, the family moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where Hill grew up. He attended Haverford College in Pennsylvania and, after graduating in 1878, went to Harvard and received a second bachelor's degree in 1879.

He returned to Minneapolis and entered into a successful law practice in which he won significant verdicts against several of James J. Hill's (1838-1916) railroads (which became the Great Northern Railway). James J. Hill was so impressed with Sam's skill that he offered him a job that expanded into the presidency or directorship of a number of Hill's companies.

In 1888, Sam married James Hill's oldest daughter, Mary. By the end of the nineteenth century, Sam Hill was a wealthy and accomplished railroad executive, financial manager, and investor, and he was active in a wide range of civic groups and fraternal organizations. He was noted for his tireless ambition and energy and for his integrity.

On to Seattle

Even before the Great Northern extended its transcontinental tracks to Seattle in 1893, Hill began examine the opportunities that the city had to offer. Through Seattle's Great Northern representative, Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925), Hill arranged for a consolidation of the Union Illuminating Company and the Union Electric Company into the Seattle Gas and Electric Company. Gas for cooking, light, and heating was manufactured from coal and piped to homes and businesses under an exclusive franchise from the city council. In December 1895, a syndicate headed by Hill acquired the company.

At the end of the 1890s, Hill began to sever his ties with the Great Northern and with James Hill's other companies, and to spend more time in Seattle. In 1898, Seattle Gas's franchise expired, but nothing was said until 1900, when the Seattle Star began to complain about the high cost of gas -- $2.00 per thousand cubic feet as against $.75 to $1.30 in other cities. Hill was an easy target since he represented utilities and railroads. Besides, he was from Minneapolis.

In 1902, some former associates of Hill's started the Citizens' Light and Power Company and began to compete with Seattle Gas. This resulted in a ruinous price war and Hill had to use his own funds to cover Seattle Gas debts. The price war ended with a merging of the gas companies (the electric light function had been sold off). Hill left the gas business in 1904. He successfully invested in the stock market, which helped fund his other enterprises. Hill wrote, "Where a man's treasure is there will his heart also be" (Tuhy, 92).

Good Roads

Hill's work for the Great Northern made him an expert in the economics of transportation. At that time, 93 percent of the nation's roads were ungraded and unsurfaced. Hill realized that if farmers could easily reach towns and rail connections, all would prosper. In September 1899, he invited 100 business leaders to a meeting in Spokane for the purpose of starting a group to promote good roads. Only 14 appeared, but they included leaders such as Reginald H. Thomson (1851-1949), Seattle City Engineer, and Frank Terrace, a farmer from Orilla. They formed the Washington State Good Roads Association and they chose Hill as president. Hill declared, "Good roads are more than my hobby; they are my religion."

The Good Roads Association advocated state spending on roads and coordination among the county road systems. Washington was slow to adopt Hill's point of view. Farmers were suspicious of Hill's connections with the railroads and Eastern capitalists, whom they blamed for all their woes. County commissioners who built and maintained the county roads with property taxes resisted any infringement on their prerogatives and perquisites. Hill and his colleagues lobbied the state legislature and stumped the state for good roads. Hill took the campaign nationwide (sometimes accompanied by trucks of furniture to insure his comfort while traveling) and to Washington, D.C., all at his own expense.

Hill even included a moral argument for good roads.

"I believe in man on the land. We cannot afford to have our producers leave the land and come to the city and become parasites. We want our girls to stay on the farm and become the mothers of a virile race of men and not just go to the city and become manicurists, stenographers, and variety actresses. We want our boys to stay on the farm and not succumb to the lure of the Great White Way or become chauffeurs and clerks ... We cannot keep the ambitious boy or girl on the farm unless we make life attractive and comfortable."

The work paid off. In 1905, the state legislature organized a state highway department. As automobile use increased, the Good Roads Movement gained adherents.

Road-building technology lagged however. There were no standards for curves and gradients and little knowledge of how to surface roads for automobiles. In 1907, Hill persuaded the University of Washington Board of Regents to establish a chair of highway engineering, the first in the nation. Soon, 200 students were enrolled. As part of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909, Hill helped organize the first American Congress of Road Builders. The Good Roads Building at the A-Y-P exposition became the highway engineering building at the University of Washington.

In 1909, Hill built 10 miles of demonstration road at his model community, Maryhill, situated on the Columbia River. He used seven different road-building techniques. These were the first roads in the state to be paved. Hill spent more than $100,000 of his own money, which was much cheaper than the $28,000 per mile cost near Seattle. One benefit of the experiment was to identify road surfaces that did not work. In 1913, Hill paid for the governor of Oregon and the entire Oregon State Legislature to visit Maryhill and view his roads.

Portland

Hill tried to compete with Bell Systems Portland Telephone & Telegraph Company when he took control of the struggling Home Telephone and Telegraph Company in Portland in March 1909. Home offered a patented automatic dialing system. The situation in Portland mirrored those around the country where small independents sought to take business away from the Bell conglomerate. Hill then became a booster of Portland as well as of Seattle and he expanded his good roads campaign to Oregon.

At first, Home did well under Hill's leadership and the competition between the companies was intense. But in 1917, the company went into receivership and its assets were sold to the Bell company. Bell eventually offered all customers Home's dialing technology.

Home Life

Hill's personal life did not enjoy the successes of his business and civic ventures. In 1902, he moved his wife and two children to his new home, but Mrs. Hill took the family back to Minneapolis after six months and she never lived in Seattle again. He bought her homes in Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., and Massachusetts. Hill took up residence at the Rainier Club, Seattle's premier private gentleman's club.

Hill's daughter developed a mental illness and was eventually declared incompetent. His son did not live up to Hill's expectations of ambition or academic excellence. Father and son did not speak to each other during the last years of Hill's life. Hill had three other children with women he did not marry.

Despite Hill's estrangement from his wife, he began construction on a palatial mansion in Seattle on East Highland Drive near Volunteer Park in 1908. Hill became active in local civic issues, helping to prepare for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (1909) and to promote Seattle as a gateway to Russia and Asia. When Hill purchased the Home Telephone and Telegraph Company in Portland, he shifted his boosterism and his good roads campaigning to Oregon.

Hill was active beyond the Northwest and the United States. He traveled frequently in Europe and to Japan gathering information on highways. In 1901, he traveled the then-unfinished Trans-Siberian Railway from Asia to Europe on behalf of French investors. During World War I, he undertook a secret mission for the Allies, starting in Europe, traveling around the world to the Russian Far East, then across Russia, to evaluate Russian railroads.

Maryhill

In 1905, Hill began to examine Klickitat County on the Columbia River for business opportunities. The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railroad was slated to run along the north shore of the Columbia and Hill recognized the agricultural potential of the region "where the rain and the sunshine meet." (Tuhy, 203) He bought property near the small town of Columbus and named it Maryhill Ranch after his wife and daughter. He built dams and tapped natural springs for irrigation and he acquired a total of 18 farms and ranches totaling 7,000 acres. His managers (Hill continued his other businesses in Seattle and Portland, his good roads campaign, and trips to Europe and Asia) planted orchards and vineyards.

In 1909, Hill tried to market land to Quaker farmers, but none accepted his offers, so he widened his advertising campaign and even offered leases. Only a few families took up land where rainfall averaged 11 inches and the wind blew unimpeded down the gorge. Hill used some of the property for his road demonstration project and often hosted tours. In 1913, Hill shifted his strategy to raising cattle, but he continued to lose money.

In 1914, Hill began construction of a mansion overlooking Oregon and the river to the south, but work proceeded slowly. The building was 60 by 93 feet and he planned eight suites and room enough for 250 dinner guests. The outer walls were built of reinforced concrete. Hill apparently became irritated with Washington state officials for not completing a highway on the north bank of the Columbia and he abandoned the project in 1917. He then considered turning the structure into a museum, which was dedicated by his friend Queen Marie of Romania in 1926. The building was not finished until after Hill's death.

Monuments

If Hill was not busy enough, he also built, at his own expense two memorials in Washington. On July 4, 1918, he dedicated a monument to three men from Klickitat County who had been killed in World War I (nine more names would be added to the list). The monument was designed as a replica of Stonehenge (the stone circle built some three thousand years ago on the Salisbury Plain in England), and was not completed until 1930. It is located three miles east of Hill's Maryhill mansion on a bluff overlooking the Columbia River. A hotel was moved to provide the memorial the best location.

The Peace Arch at Blaine was completed in 1921 on the boundary between the United States and Canada to celebrate 100 years of peace between the two nations and the longest undefended border in the world. The Peace Arch was dedicated in 1921 and again in 1926 by Hill's friend, Queen Marie of Romania, a popular celebrity who was touring the United States on a special train, with Hill accompanying Her Majesty on the Washington part of the tour. On the day of the Peace Arch dedication, members of the entourage had, apparently, been squabbling. On November 8, 1926, the Queen recorded in her diary:

"The ceremony was simple with a touch of the absurd because old Hill is scatter-brained and simple in spite of his world-wide schemes. We might have been in Tara Mea as far as the music, schoolchildren, flags, singing, etc ... it was touching and absurd but of course there were the usual speeches which were all about peace, giving a comic note because of the squabbles that had just been going on in the train. Old Hill felt it and whispered to me that he felt ashamed to speak of peace and I understood why. I did!" (America Seen by a Queen, p. 106).

Like Hill's two large homes and Stonehenge, the Peace Arch was built of reinforced concrete.

In the 1920s, Hill's fortune began to wane. He engaged in ventures as diverse as a resort at Semiamhoo, a coal mine in Alabama, three history books, a motion picture, and a world-wide chain of peace memorials patterned after King Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. Historian John Tuhy speculates that Hill suffered from manic depression, which would explain his bursts of widely directed energy.

Hill was stricken with "intestinal influenza" (Tuhy, 276) while on his way to address Oregon's governor and legislature. He died two weeks later on February 25, 1931, in Portland. His ashes were entombed near the Stonehenge memorial.

Half of Hill's estate was left to the Maryhill Museum. His wife and son contested the bequest and it took 15 years to finally resolve all issues and dispose of all property. (He left trust funds for each of his other children.)

The trustees of Maryhill Museum struggled to complete the building and to protect the collection while Hill's estate wound its way through the courts. The museum finally opened on May 13, 1940, Sam Hill's birthday. By 2002, the Maryhill Museum of Art saw 10,000 visitors a month.

Hill's dream of the Pacific Highway was supplanted by Interstate-5 in the 1960s and 1970s. Not only was the trip from Canada to Mexico all paved, it was nonstop.

Most of the stories about Sam Hill are apocryphal. His name is not the basis for the saying, "What in Sam Hill ..." He did not meet J. J. Hill when Sam was a station master. J. J. Hill did not sponsor Sam's education. Hill did not room with Prince Albert of Belgium at the University of Munich (Hill purportedly learned the prince's identity when he accompanied his roommate home for Christmas). Hill himself was responsible for many of these legends and journalists of the early twentieth century were happy to repeat them.