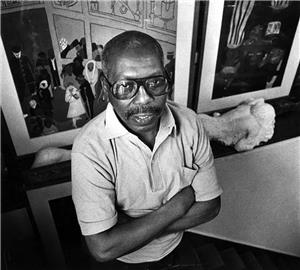

Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight, two of the country's preeminent visual artists, moved to Seattle in 1971 when he accepted a teaching position in University of Washington's art department. The two met and wed in Harlem in 1941 and later built national reputations as painters and printmakers, and as art educators and activists. Jacob Lawrence died in Seattle on June 9, 2000. Gwen Knight died on February 18, 2005.

Lives in Art

"If at times my artworks do not express the conventionally beautiful, there is always an effort to express the universal beauty of man's continuous struggle to lift his social position and to add dimension to his spiritual being" -- Jacob Lawrence, 1970

Jacob Lawrence was born in 1917 in Atlantic City, New Jersey. He moved to New York City in 1930 at the age of 13. His family, originally from the South, migrated north looking for work. Jacob remembered New York as a vibrant community bustling with noises, sounds, and smells alive all around him. For this bright-eyed young man, Harlem was the churches, storefronts, street vendors, libraries, artist’s studios, museums, and eateries peopled by a tight-knit community of people who all knew each other. "We didn’t all know each other personally," he’d say, "but we knew each other by sight because we saw the same people on the street every day." There was a comfort in seeing those same faces every day.

Gwendolyn Knight, born in Barbados, West Indies, came to the United States with her family when she was 7. She lived in Saint Louis until she was in her early teens, when she moved again with her family, this time to New York. While she cannot remember when she first decided to become an artist, she recalls completing her first paintings when she was 8 or 9 years old. She too, was nurtured by the burgeoning community in Harlem. "We had every thing we needed," she said, "stores, libraries, restaurants, artist workshops, and theatres. We didn’t have to go anywhere else to find it because it was all right there." It was a rich time, and she and Jacob never ceased to pay homage to those in Harlem who played a pivotal part in their development.

It was the 1930s and people were poor, but they brightened their lives with color. They painted the interiors of their apartments in bright tones. There was pattern and color everywhere. Many of Jacob’s paintings from the 1930s and 1940s chronicled, in large blocks of color sometimes delineated in bold outline, people on their stoops, street orators, pool halls, funerals, and the huddled poor. Drawn by the historical narrative, his paintings told the stories of Toussaint L’Ouverature (leader of a slave revolt in Haiti), John Brown, and Harriet Tubman and the migration of African Americans from the South to the north. "It was alive for me," he said. "I didn’t see a difference in what was happening around me and the stories I painted."

He described in amazement the Harlem community’s concern for the welfare and education of its young people. "They talked to us about our history, engaged and encouraged us. They were proud of everything we did." In 1932, he found himself, through a turn of good fortune, in the studio of Charles Alston. There he found work-space and instruction. The older artists like Claude McKay, Charles Alston, and Augusta Savage (1900-1962) were role models and mentors. "We looked up to them. They often gave us art materials, instruction and a place to paint."

The Influence of Augusta Savage

One of the people both Jacob and Gwen credited was Augusta Savage. A well-known sculptor in Harlem in the 1930s, she was also an activist and ardent supporter of education and opportunity for young people. She spotted Jacob Lawrence as a young talented person. In 1934 -- when he was 17 -- she personally escorted him to the office of the Works Progress Administration (WPA -- a federal program to put unemployed people back to work), to apply for an art project. His first application was refused because he was too young. Told to apply again a year later, Jacob recalled he didn’t give all of this too much thought. Yet, one year later, there was Savage, on hand and guiding him to make sure that he returned to apply again. It was with the second application that he was accepted as an official member of the WPA Artists' Project. This was Jacob’s first paying job as an artist.

Jacob met and married Gwendolyn Knight in 1941. In 1943, Jacob was drafted into the U.S. Coast Guard, where he served during World War II until 1945. In 1946, he taught briefly at Black Mountain College (North Carolina) at the invitation of Josef Albers, whom he credited with influencing his teaching style by emphasizing the importance of basic design elements. Teaching would become a twin passion with painting, leading him in 1954 to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, followed by assignments at The New School for Social Research, The Art Students League, and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

For Gwen, Augusta Savage was also a mentor whose mastery of the figure helped guide her interests and vision as a figure painter. Savage helped her develop technical skills and a work process where she used the figure as a base in her compositions. The power of Savage’s influence persists in Gwen’s work. A hallmark of her paintings continues to be the human, though more recently animals have appeared. With both, she incorporates figures as structural and emotional narrative components.

Jacob recalled his first impression of Gwen being that she was a serious artist. She had a love for all the arts -- dance, music, and visual arts. She had studied for a time at Howard University, and thus was able to bring an academic perspective as well as a working-artist view to her discussions of art. Jacob said, "In our life together we share our opinions but reserve them until one or the other of us is ready to discuss the work. Once we’ve commented on each other’s work we were free to choose whether or not we make changes based on those comments. There really was no pressure. Sometimes you wouldn’t even understand a remark until years later."

Gwen and Jacob lived and painted in New York during the height of Abstract Expressionism. Although this major art movement of the 1950s and 1960s gained great critical attention, Jacob never detoured from his love of the figure and continued to paint the human experience. He would expand his genre to include the civil rights struggle, aviation, and builders and their tools. No human experience was too commonplace to be honored by his brush.

The Move to Seattle

In 1971, Jacob Lawrence accepted a teaching position at the University of Washington’s School of Art. He and Gwen picked up their lives and moved to Seattle, thinking they would spend four or five years before returning home to New York. As part of the move and their effort to become part of the community, they bought a house that was near both the University and a bus stop. They set up studios in the house. For Jacob it was a small, low-ceilinged attic room at the top of the house and for Gwen it was a converted space off the garage. There, in these modest spaces, they would create monumental works of art.

For apartment dwellers who had never owned a car or a freestanding home, all of this was an adventure. They walked or took the bus nearly everywhere they went. Of the house, one of them said, "There were so many doors and windows it was hard to get used to. And the unfamiliar creaking sounds would startle us in the middle of the night." Jacob and Gwen found the differences between Seattle and New York both dramatic and subtle. They were used to the foreign element, of being in a cosmopolitan place where the outside world was constantly coming in. In Seattle there was less of that.

Jacob observed that in the Northwest there was a subtle difference in the quality of the light and in how his students responded to color. In the east, artists seemed more concerned with tonal color. In the west there was a concern for prismatic color. Jacob and Gwen found these cultural and artistic challenges exciting.

The Seattle years of 1971-1986 were filled with making art and being active members of the community. When asked to compare Seattle with the life they left behind, they both said that art creates a community. Just as in New York, they were able to find their place in the Seattle arts community. They were active members both of the University community and the community at large. They worked with local civic organizations such as the Urban League, and the Seattle chapter of Links. Gwendolyn served on the King County Arts Commission and Jacob on the Washington State Arts Commission. Together they also clocked in hundreds of hours on art panels and juries, locally, regionally, and nationally. And for Jacob there was also teaching at the University, an activity he loved. This proved to be a distinct benefit for the hundreds and hundreds of students who would have the good fortune to pass through classes under his tutelage, whether or not they went on into the world as working artists.

Lasting Legacies

Jacob Lawrence was a lover of tools. The objects of everyday life -- hammers, saws, nails, wooden planks, and boards, he saw as a means to extend the body. He created compositions that honor the simple but necessary. Books, book carts, shelves, and readers are caught in the act of the unremarkable. Shoppers wander amid grocery carts, canned goods, produce, in rows where birds and flowers spring forth from the aisles. History comes alive. Our blights, misfortunes, and honors are captured and stilled. Slavery, slaves chased, caught, hung. War, bombs, the bombed, burned. The winner, the inaugurated, hailed, and heralded.

Gwendolyn Knight was a lover of the animal and human form. She chose dancers, or sitters whose figures shape the space and create emotional and structural tension. They are folded and arched or they leap and unravel across the surface of her paintings like untied pieces of string. There is the carefully studied face, where youth hangs fragile on an eyelid or the gestured mark that captures a whole history. There are horses that run through dream space in black and white. Even in her simplest still-life paintings she revealed her mastery for manipulating the figure/ground relationship.

Life was full: there were exhibits, traveling shows, honorary degrees, and awards. Five years turned into 10, marked later by the milestone of Jacob’s Emeritus retirement in 1986 from the University of Washington. While they never moved back to New York, they traveled there often for business -- frequent exhibitions -- and pleasure. In the 30 years since they arrived, Seattleites came to think of them as their own.

Jacob Lawrence died on June 9, 2000. His death at 82 closed a brilliant career and 59 years of marriage. Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence had a life’s adventure together few will ever know. In September 2000, the University of Washington Press published a catalogue raisonné of Jacob’s work compiled and edited by Peter Nesbett and Michele Dubois. It is the first catalogue raisonné ever done on the work of an African American artist.

Of the two, Jacob had certainly been the most lauded. But Gwen had a quiet steady triumph of her own. She said, "My life with Jacob allowed me to work as I pleased. I’ve never felt overlooked. I’ve been lucky." When either was asked about their lives, they said it had been a pretty normal life. But at its center was the solidity of their beginnings. The thriving Harlem community filled with characters, color, and history that informed and nourished them. It was ballast as important as the artwork they both so faithfully created.