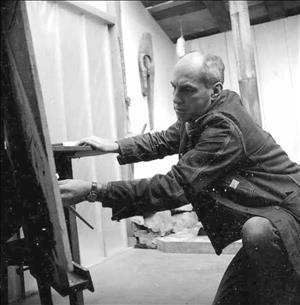

Guy Anderson was, according to Bruce Guenther, former curator of modern art at the Seattle Art Museum, "perhaps the most powerful artist to emerge from the Northwest School." Partly by virtue of his semi-reclusive lifestyle, and partly through the profound gravity of the giant paintings that issued from his studio, Anderson occupied an elevated niche in the Northwest art world. This biography of Guy Anderson is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

Painting a Manifestation of the Human Spirit

Fellow painter William Ivey wrote in 1977:

"Of particular importance to me, in a time in which few painters appear to have faith in the ability of painting to express one's deepest perceptions and instead have settled for painting as entertainment or titillation, or decor, is the steadfastness with which Guy Anderson has maintained a belief in the possibility of painting being much more a manifestation of the human spirit" (Ivey).

Anderson was born in a rural house near Edmonds, Washington, on November 20, 1906. His father, Irving Lodell Anderson, was a socialist, a multi-talented carpenter-builder who played the clarinet and led a musical group (Wehr).

From early boyhood, Guy was intrigued with other cultures. He was particularly struck by Northwest Coast Native American carvings, with their soft-cornered squares and ovoid eyes, and flashes of color set against woody earth browns. The juxtapositions of shape and color sank deep into his consciousness, to re-emerge years later in his own pictorial vocabulary, having melded with motifs from Indo-European mythology. As Sheila Farr noted in a Seattle Weekly article, many artists may appropriate mythical themes and archetypes in the hope of suggesting universality, but Anderson discovered a true universality (Farr).

A prime example is his Primitive Forms II, in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum. Painted in 1962, it contains elements of Northwest Coast Indian art magnified to emphasize the art to which it pays homage and to point up shapes that appear in nearly identical form in ancient Chinese bronzes.

Teachers and Mentors

Anderson was introduced to Asian art at age six, when he saw Japanese prints in the collection of his first grade teacher, Mabel Thorpe Jones. Anna Vassett, who was both his sixth grade teacher and his piano teacher for 10 years, had lived in Asia as the wife of a missionary. He later said that studying music in the company of her large collection of Asian objects taught him to recognize the importance of the time element in both music and painting.

Art interested him even in childhood. When he was old enough to do so on his own, he used to commute to the Seattle Public Library by bus to spend evenings studying art books, saddened by missing color plates.

The painting technique he developed was largely self-taught, although he owed his predilection for oil paints to Alaskan scenic painter Eustace Ziegler, with whom he studied briefly after graduation from high school, when Ziegler had a studio in the White Henry Stuart Building, in downtown Seattle. Ziegler, who had been trained at Yale University, offered a professional program in life drawing, still life, portraiture, and landscape painting (Wehr). He took his students on excursions to visit the art collections of Charles and Emma Frye and Horace C. Henry. (The Frye collection became the core collection of the Frye Art Museum. The Horace Henry collection formed the initial collection of the Henry Art Gallery.)

Anderson said Ziegler was in love with painting but often turned out potboilers -- in his case, daubs of Mount McKinley -- for income to support his family. Under Ziegler's tutelage, Anderson learned to draw the nude figure, a form central to his vision. With Ziegler's guidance, Anderson bought his first art book: The Drawings of Michelangelo. It was a volume he treasured until the end of his life. A perusal of his paintings in subsequent years occasionally reveals figures that appear to have been directly inspired by Michelangelo's sculptures.

Art Worlds

Seattle had no art museums when Anderson was growing up. He got his first chance to see world-class art in 1929, when, encouraged by illustrator Ernest Norling, he applied for and won a Tiffany Foundation scholarship. He spent the summer at the Tiffany estate on Long Island, New York, joining other aspiring artists from around the nation.

He spent weekdays painting landscapes, receiving formal weekly critiques on his work from Louis Comfort Tiffany and other artists of established reputation. On weekends, he visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reveling in the work of Rembrandt, Goya, Daumier, Turner, Ryder, Whistler, and Sargent. He had stopped in Chicago on his way to New York to visit the Chicago Art Institute, with its magnificent collection of French impressionist canvases.

Friendship with Morris Graves

When he returned to the Northwest, Anderson set up a studio in a small outbuilding by his parents' home. He experimented with pointillist impressionism, and with formal portraits. He limited his palette to black and white and very few colors. When he exhibited his work in a group show at the Fifth Avenue Gallery in 1929, a 19-year-old named Morris Graves, who lived nearby, sought him out at his studio.

The two of them immediately hit it off, finding common ground in their interests in painting and philosophy. Anderson introduced Graves to the use of oil paints, applied in slab-like strokes with a palette knife, like icing a cake. (The technique is visible in Graves's 1933 painting Moor Swan, in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum.)

In 1934 and 1935, Anderson and Graves motored down through Oregon and California together in an aged white milk truck they had pooled their money to buy, attempting with high spirits and minimal success to sell paintings along the way. Arriving in Los Angeles, they camped out behind a billboard on the outskirts of Hollywood, until police rousted them.

Graves painted a series of six canvas panels decorated with emaciated dogs, which he hoped film star Katherine Hepburn would buy. She gave them barely a glance before ordering them out of her sight. (Two and one-half of those panels are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Northwest Art, in La Conner.)

Graves stayed on in Los Angeles to work for a decorator, while Anderson and a friend hitchhiked on to Texas and into Mexican border towns. Anderson hopped a freight train and when the train pulled into L.A., found himself arrested, along with others making use of the same free transportation. He spent two months in jail before returning to the Northwest.

Back in Seattle

Anderson worked sporadically at the new Seattle Art Museum, installing shows and teaching children's art classes for a few years. He won the Katherine Baker Purchase Award in the Northwest Annual Exhibition in 1935; and the following year, the museum mounted a solo exhibition of his work.

In 1937, Graves, who had also returned to the Northwest, found the shell of a burned-out house near La Conner, a small town 65 miles north of Seattle, in the Skagit River delta. He invited Anderson to share it. The living room had the earth for floor, and chunks of driftwood as tables. Anderson recalled, "I hacked a bench out of cedar, with curling end arms, and painted it a dull Etruscan red. My friends called it Recamier Rustique" (Anderson Interview).

Depression Days

Both Anderson and Graves found work with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Art Project during the Depression. Anderson was sent in 1939 to teach at the Spokane Art Center, where Carl Morris directed a faculty widely considered to be the nation's best. It included Clyfford Still and the gifted sculptor Hilda Grossman Morris. Anderson's pay was $100 a month, but he later told Wesley Wehr that he felt enriched by having Tobey's painting Cirque d'Hiver on one wall of his room and Paul Klee's painting In the Spell of the Stars (on loan from a friend) on another. During his two years in Spokane, Anderson experimented with abstraction and cubism, and with found-metal collage using rusted, flattened tin cans.

In 1941, when he returned to Seattle, Anderson entered into the intensive social life that existed among the Callahans, Graves, Tobey, and several other artists for the brief period before World War II. The group met in Tobey's studio, or at the Callahan home, for brisk discussions of how art might embody social and moral messages without reducing itself to poster art or propaganda. Anderson shared a cabin with the Callahans near Granite Falls during the summer, and often visited Graves in the La Conner studio, where he worked during the off periods of his off-and-on employment at the museum.

Anderson became intrigued with creating sculpture from driftwood, found in abundance on Washington beaches. A Seattle floral shop whose name has not been preserved was exhibiting his driftwood sculptures when Francis Wright, sister of noted architect Frank Lloyd Wright, passed through Seattle and saw them. Impressed, she arranged an exhibition of the driftwood sculptures at America House, the craft gallery she operated in New York. The show reportedly sold out and was followed by a repeat performance several months later. Anderson seems not to have considered the America House shows sufficiently serious to include in the chronology of his exhibitions, nor did he continue to work with driftwood.

To augment his income, he gathered water-polished stones from ocean beaches and used them for mosaic patios commissioned by art collector Anne Gould Hauberg and gallery owner Zoë Dusanne.

Anderson went with anthropologist Dr. Erna Gunther to ceremonies in tribal longhouses on the Swinomish Reservation -- possibly on some of the same occasions Helmi Juvonen was present. He shared with Tobey a fascination with the similarities between Northwest Coast designs and motifs used on ancient Shang dynasty Chinese bronzes.

Like nearly all Northwest artists during the 1930s and early 1940s:

"[Anderson's] palette at the time was umber, rust, charcoal, and ice, even to the collaged addition of rusted fragments of metal, a tangible symbol of flux and disintegration" (Farr).

He regularly won awards for his work in the Northwest Annual Exhibition. Leo Kenney recalled:

"Guy loved Dr. Fuller, and he didn't mind working at the museum, but it paid very little. A mysterious person from east of the mountains came to Guy's [1945] show at SAM. In those days, Guy's work topped out at $500, and you never expected to sell anything priced that high. Most of it was $200 to $250. In those days you could buy a Tobey painting for $200. The stranger bought almost all of Guy's show. So Guy quit the museum, went to Granite Falls, and built a studio in an old apple orchard" (Kenny Interview).

Anderson came to national attention with the publication of the best-known article ever written about painting in the Pacific Northwest, in the September 28, 1953, issue of Life magazine. The piece, which appeared without a byline, was written by Vassar College arts graduate Dorothy Seiberling, a Life staff writer. Photos were by Life photographer Eliot Elisofon, who postponed work on the film biography of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Moulin Rouge, to shoot the story. It featured Anderson and Kenneth Callahan along with Tobey and Graves, who had already made a splash in New York. Callahan is said to have disapproved of Anderson's inclusion, feeling that Anderson's art was less developed than that of the other three (Meitzler Interview).

Life in La Conner

During the 1950s, Anderson was dividing his time between La Conner and Seattle, teaching in both places. During the summer, he taught at Ruth Pennington's Fidalgo Art School, then often spent the winter in La Conner. In 1959, after a year spent teaching art at Helen Bush School in Seattle, Anderson moved to La Conner permanently, to a rented house at the edge of a field on Axel Jenson's farm. (His last Seattle residence was on 15th Avenue NE, on a site that is now the parking lot of the University of Washington Book Store.)

La Conner is home to fishermen, artists, shopkeepers, Native Americans, and farmers. Forested mountains ring low-lying tulip fields and apple orchards. Massive gray barns slump into fields edged with tangles of wild rose and blackberry. Anderson especially loved it "when the maples come out across the Swinomish Channel, and I can see them against the long sweep of water" (Guenther). Bruce Guenther pointed out, "Insisting at no small cost to his career to live without an automobile in the relative isolation of La Conner, Anderson freed himself of the pressures of fashion and the marketplace" (Guenther).

His art thrived. In the loamy Skagit Valley, misty sunshine is punctuated with attacks of wind and rain. It is a climate calculated to evoke richly romantic art, such as the myth- and symbol-laden art of the region's indigenous people. It was in this environment that Anderson hit full stride as a painter. His signature style is a painting divided horizontally into two distinct parts, with the upper portion typically smaller and darker than the lower. On top, figures float, suspended above "a roiling sea," a fractured landscape, or a gigantic luminous orb that dwarfs them (Farr).

The figures are sometimes isolated dreamers; at other times, encapsulated embryos. Whether floating or fragmented, the figures carry a "sense of potential" (Farr), of coming into being, or passing between levels of reality. They suggest the concept of souls in transport.

The ground over which Anderson's figures float embodies the great dragon forces of nature. Giant circles that wheel beneath them imply at various times the cosmos, the sun, the womb, or a seed. Titles such as The Birth of Adam express Anderson's intention. Sometimes, as in Seed and Cosmos, he shows how microcosm reiterates macrocosm. In a painting titled Spring, the circle becomes a dark bomb crater, and the airborne bodies, fragments of corpses.

In Through Light Through Water, men are reduced to anonymous body parts on beaches lit by a phosphorescent nuclear glow. Anderson painted it to express his revulsion for war. Red in his paintings nearly always implied blood -- usually the trauma of birth or death. Because he used color sparingly, it carries strong visual impact whenever it appears.

In addition to the La Conner landscape, another influence was at play in Anderson's work: the Asian art that filled the Seattle Art Museum. While European art typically placed the figure central in a composition, Anderson tended to float it high or tuck it into a corner, in keeping with the classical Asian theme of showing man small against the grandeur of nature. He adopted Asian-style formalized wave patterns of water, and employed a spontaneous Zen style of brushwork, albeit with oils rather than ink. The track of his fully charged six-inch brush across an eight-foot surface is a feat of pure muscular energy.

Unlike Tobey and Graves, Anderson never painted in gouache or tempera. Introduced to oils by Ziegler, he continued to use them throughout his career, taking pleasure in their texture and surface. Sometimes he did charcoal underdrawings of the figures in the paintings, going over them with a broad felt-tip pen or thinned oil paint and chalk, sealing such drawings with a matte finish spray before proceeding with larger gestures in oil.

After years of painting on stretched canvases, in the late 1960s Anderson discovered two-ply construction paper laminated with tar and reinforced with mesh. It was strong, cheap, and available in large rolls, a step up from the feed sacks and paper bags he and Graves had used as painting surfaces in their lean, hungry days.

The paper's giant size allowed his brushwork to open up into cosmic whorls and broad, snaking waves that symbolized the churning of the milky sea of the Vedic creation myth. He laid out great swaths of it on his studio floor, walking on the painting in the process of creating it (in some of his paintings, faint footsteps remain visible), turning out a few paintings so large they could not be exhibited because they literally could not be gotten in through the door of the Francine Seders Gallery, his dealer for the greatest part of his career. (He subsequently delivered his paintings to the gallery rolled up rather than on stretchers.)

Anderson scarcely cared that, as Sheila Farr notes, construction paper is a conservator's nightmare. The pleasure of painting on a grand scale outweighed concerns about the longevity of his work. Solvents in oil paint thinned with turpentine draw the tar to the surface of the paper, darkening it, sometimes allowing the pattern of the mesh to read through, like a faint grid on which figures are superimposed. Paper conservator Alice Bear cautions that the paintings will continue to darken over time unless special conservation measures are taken. When construction paper is rolled, as Anderson was accustomed to do with his finished pieces, thick applications of oil paint are prone to crack and chip (Farr). Similar cracking can occur over time as a result of movement of the tar layer.

Anderson's bravado brushwork with its knotted undulations was well suited to the grandeur of his themes. No Northwest painter ever tackled bigger topics. The concern of his paintings is nothing less than man's place in the universe. His subjects encompassed classic myths such as The Birth of Prometheus and the Dream of the Language Wheel, inspired by Mayan glyphs. It was heady stuff for a modest man.

A High-Spirited Eccentric

In his prime, Anderson weighed 157 pounds and stood 5 feet, 7 inches, but he always seemed taller. His habitual attire was tennis shoes and a fisherman's sweater worn with a scarf knotted around his neck as an ascot. Anyone who knew him could not avoid being impressed by his unfailing sweetness of disposition, and the impish sense of humor that could lead him to open the door to a stranger, clad as a maid, complete with starched cap, or to answer his telephone with a curt "Bog Tule." It was not necessary to know that he used to dye his Jockey shorts a shade of Japanese mauve to appreciate that he was a high-spirited eccentric.

The paradox of Anderson lies in the contrast of the weighty themes that predominated in his paintings with the joie de vivre that invigorated his martini-sipping, bon mot-swapping, music-loving life. He was unfailingly charming, witty, and articulate. Tom Robbins placed his manner somewhere between Oscar Wilde and Cary Grant: lusty but sophisticated.

Anderson seems never to have suffered the doubts and depressions of his compatriots who moved away from the Northwest and enjoyed -- more often suffered through -- major reputations and career crises. Staying connected with his roots, he derived lifelong nourishment from his environment.

Declining Fame

He had four chances that might have led to his becoming better known on the national art scene. He declined two of them and experienced uncommonly bad luck with the other two. In his unpublished memoir of Anderson, artist Wesley Wehr recalls that Marian Willard, who represented Tobey and Graves in New York, offered Anderson a solo exhibition in 1948. Anderson declined, saying he didn't have enough work available.

He said no again in 1952 when Andrew Ritchie, director of the Museum of Modern Art's department of painting and sculpture offered him an exhibition. He was seemingly prepared to accept a show in Paris in 1950 or shortly thereafter, when it was offered by Alexander Rabow, who saw one of Anderson's paintings in an exhibition at the Oakland Art Museum. Unfortunately, Rabow died before Anderson could gather work for the show. Anderson at last had a solo exhibition in New York in 1962, at the Smolin Gallery. A newspaper strike was in progress, and his show was one of many that went unreviewed. Whatever his expectations may have been, Anderson returned to life as usual in La Conner.

A Simple Life

He shared with Graves the ability to create a gracious environment with minimal means. He built a combination house and studio of his own design on a side street in La Conner. His painting studio occupied the entire second floor. In the rear, narrow strips of windows eight-feet tall were designed to simplify the process of moving large paintings in and out of his studio. (One of his largest paintings, Between Night and Morning, commissioned for the Skagit Valley Court House in Mount Vernon, measured 7 by 13 feet.)

A grand piano occupied a central spot in his living room, topped with African art, a rusty oil can that served as a sculpture stand, silver candlesticks, and a rock that carried the imprint of a fossilized blossom -- a gift from Wesley Wehr. Although he denied any great musical talent, Anderson played the piano with great enjoyment. His love of classical music directly influenced his paintings. Artist Leo Kenney likened the rhythms and silences in Anderson's paintings to musical compositions that can be felt as well as seen (Kenny Interview).

In 1974, in the catalog for an exhibition of his work at the Whatcom Museum of History and Art in Bellingham, Anderson wrote:

"Timing has to be in operation throughout the composition, making accents at the predetermined points of stress. This is pictorial timing. The other kind, the all-over timing of Pollock and Mondrian which gives equal stress to every area of the picture surface, doesn't interest me. Life is not equally timed. Fingers accent an arm, blossoms accent a tree. Painting which is timed in this way is truer to what existence is all about.

World Travels

In 1966, at the age of 60, Anderson made his first trip to Europe. He traveled to France, Italy, and Greece in the company of artists Barbara and Clayton James and photographer and art historian Phyllis Dearborn Massar.

In 1975, nearly 50 years after his Tiffany Foundation Scholarship, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. He used the money to travel east, to study the paintings in major museums in New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. That done, he traveled south to Mexico City and Oaxaca and the Yucatan, fulfilling a long-held desire to see Mexico.

Last Years

Anderson's energy began to flag in his 80s. As he became frail, he relied increasingly on his younger friend and companion Deryl Walls. They had met through a mutual friend who modeled for Anderson, and had become sufficiently close that Walls accompanied Anderson on trips to San Francisco in 1978 and Osaka, Japan, in 1982, when Anderson's art was featured in those places.

Walls said:

"He was really like my own grandfather. As he became frail, he needed someone nearby. I committed myself to seeing that he could live in his own house as long as he wanted. Then one evening in 1996 after we'd been out for dinner and I'd dropped him off at home, he fell in his kitchen, and lay there all night because he couldn't get up. He was quite frightened, and so was I when I found him there the next day. I took him to the hospital. He had a touch of the flu."

Walls brought Anderson to his own home to care for him, with the help of a nurse and a therapist. After a series of small strokes over the next two years, Anderson lost the ability to speak. By the time of his death, at 91, he was in a wheelchair. Walls was named executor of his estate, and its chief beneficiary. In an adjunct to his home in Mount Vernon, he opened Gallery Dei Gratia, devoted to the large number of paintings left in Anderson's estate at the time of his death. [Editor's note: Walls's handling of Anderson's affairs was extremely controversial. See Sheila Farr, "Guy Anderson at 90," cover story, Seattle Weekly, July 24, 1996.]

A Mystic to the Core

Anderson's paintings carried the ambiance of Puget Sound's misty light, mountains, and green woods. But they were pulled in equal part from a deeper source -- from the unconscious birthplace of dreams that bubble to the surface to express as symbols. A mystic to his core, Anderson recognized that a symbol transcends the one who makes use of it, and expresses more than he is capable of expressing.

He once wrote:

"Whether the condition of this world in its light and dark hours changes greatly for the enlightenment of man, he still is a night swimmer among its mysteries. I read the Vedanta and the Vedas, and I think about the order of the universe. The more we send men out into space, the more I realize we already are in space, floating out there. The whole order is preordained, in some miraculous way. I think all creation is magical" (Ament Interview).