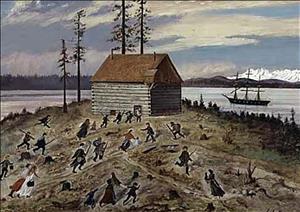

On the morning of January 26, 1856, after months of raids and clashes with federal troops in southern King County and in Thurston County, Native Americans attack Seattle. Previously warned by friendly Indians, most settlers had barricaded themselves in a blockhouse. The attackers are driven off by artillery fire and by Marines from the U.S. Navy sloop-of-war Decatur, anchored in Elliott Bay. Two settlers and an unknown number of raiders perish in the all-day "Battle of Seattle."

Seattle's Treaty War

This episode in the treaty wars occurred due to Indian frustrations with with treaties pushed upon them by Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862).

On Sunday, October 28, 1855, Indians attacked and killed settlers in south King County and in Thurston County. Acting Governor Charles Mason ordered the formation of four companies of militia to rendezvous at Seattle. The settlers of Puget Sound built more than 60 block houses as well as stockades. In December, Indians ambushed U.S. Army Lieutenant Slaughter and killed him on Brannan’s Prairie near the future Auburn.

On orders from Indian Agent Michael T. Simmons (1814-1867), local Indian Agent Dr. David S. Maynard (1808-1873) removed 434 Indians from the Seattle area to the west side of Puget Sound. Maynard accomplished this at his own expense and with the assistance of his wife.

The Decatur

The U.S. Navy Sloop of War Decatur had been stationed in Puget Sound both in anticipation of trouble with local Indians, but also as a deterrent against Indians from Vancouver Island who regularly raided Indian and American settlements. The Decatur anchored in Elliott Bay and the crew assisted in constructing a blockhouse for Seattle. Captain Isaac L. Sterret of the Decatur contributed some Marines, two nine-pounder cannon, and 18 stands of arms to the defense effort.

Tensions eased until January 1856 when word of renewed hostilities reached Seattle. Governor Stevens arrived in Seattle aboard the USS Active on January 21 and discounted rumors of war. Less than an hour after Stevens sailed away, new information came in. Various reports credit Chief Seattle (178?-1866), his daughter Angeline (1820-1896), and Curley (Sucquardle) or Curly Jim for warning Seattle's 50 or so white residents that an attack was imminent. Chiefs Owhi and Coquilton reconnoitered the lines, disguised as friendly Indians, on the night of January 25.

In response to warnings, the Decatur's new commander, Guert Gansevoort, ordered Marines ashore early on the morning of Saturday, January 26. On being warned by Nancy (Kicumulow), Curley’s sister and Indian Jim’s mother, gunners from the Decatur lobbed a howitzer shell at the house owned by Tom Pepper on the forested crest of First Hill, believed to shelter hostiles, at about 8:30 a.m., and raiders replied with a fusillade of gunfire. Seattle residents and refugees from previous attacks in southern King County took shelter in the two blockhouses. The village also teemed with dozens of friendly Indians, including the wives and children of settlers. These people crowded into the defile along the beach for protection.

The Battle of Seattle

The guns of the Decatur fired solid shot, shells (which exploded after impact), grape shot, and canister into the trees sheltering the attackers (along where 3rd Avenue would later be built). Volunteers under militia Captain Christopher C. Hewitt contributed fire, but it was the range of the Decatur’s guns that kept the Indians at a distance.

Sporadic exchanges of fire continued until 11:45 a.m. when the Indians apparently paused to eat. The settlers took advantage of the lull to evacuate women and children to the Decatur and another ship, the Brontes. Sawmill owner Henry Yesler prevailed upon his Duwamish consort, Susan (daughter of Curley), to take refuge with their infant daughter aboard the ship, despite her objections. When settlers attempted to retrieve arms and valuables from their abandoned homes, the Indians resumed firing.

Desultory exchanges then resumed and continued all afternoon. When scouts reported that the Indians were preparing to light fire to settler dwellings, the Decatur shifted its fire to the homes, damaging several. By 10 p.m., all firing stopped.

Aftermath

The next morning found the attackers gone along with whatever settler stock, foodstuffs, and other property they could take. Two settlers were killed, Milton G. Holgate and, according to historian Clarence Bagley (quoting William Bell two days after the event), Christian White. (Phelps, writing 17 years later, stated that this second man killed was Robert Wilson.)

Estimates of the number of Indians killed varied wildly. According to Isaac Stevens, writing to Washington, settlers estimated that 200 to 500 Indians had taken the field against the settlers. T. S. Phelps, the navigator on the Decatur, put the number of enemy at 2,000, but frontier military officers often inflated the number of opposing forces to reinforce their accomplishments (or to minimize their failures). No Indian bodies were found at Seattle.

With lumber from Yesler’s mill, the residents began construction of a 3,600-foot-long stockade, two fences five feet high, 18 inches apart, and filled with earth, and another blockhouse. Within three weeks, the new fortifications were complete, along with fields of fire cleared of stumps and brush.

Snoqualmie Chief Pat Kanim solicited a bounty for the heads of those who attacked Seattle -- $80 for a chief and $20 for a warrior -- and historian Clarence Bagley notes, “During the month of February 1856, several invoices of these ghastly trophies were received and sent to [Olympia]” (Bagley, 74). Governor Stevens ordered courts martial of some 20 Indians implicated in the attack, but the evidence showed they were engaged in legitimate warfare and were discharged.

Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens and others blamed the attack on Nisqually Chief Leschi and Klickitat/Yakima Chief Owhi, both of whom were later captured. Owhi was captured and killed by troops led by Col. George Wright during the subsequent Coeur d'Alene War. Leschi eluded capture for a time, thanks in part to the non-cooperation of settlers who felt he had been falsely accused of unrelated murders. Despite a strenuous, year-long defense to save his life (argued in part by Bing Crosby's grandfather, H. R. Crosby), Leschi was hanged at Fort Steilacoom on February 19, 1858.

Governor Stevens also implicated Kitsap of the Muckleshoot and Suquamish as an instigator of the violence, but the settlers did not see it that way. Residents on the west side of Puget Sound named their new county Kitsap.

Denny Won't Go

The Territorial Volunteers only grudgingly accepted command by U.S. Army officers. When Lieutenant Arthur Denny of Company A was ordered to dispatch men to Fort Steilacoom, he refused, claiming the company was intended for local defense. He was relieved of command. The company protested his dismissal in writing and all were refused an Honorable Discharge. Only an action by the Territorial Legislature reversed this decision.

Settlers in present-day King County were never again molested, but the Battle of Seattle shook the confidence of many pioneers. In 1857, Dr. David Maynard (1808-1873), who had helped put Seattle on the map and served as King County's Indian Sub-agent, exchanged his claim to present-day Pioneer Square for Charles Terry's holdings in West Seattle, and thereby traded away a potential real estate fortune for a fleeting sense of security.

In the words of Arthur Denny, “The winter after the war closed was a period of pinching want and great privation such as was never experienced here except in the winter of 1852-53. Those who remained until the war closed were so discouraged and so much in dread of another outbreak that they were unwilling to return to their homes in the country and undertake the task of rebuilding ... and in consequence it was years before we recovered our lost ground to any extent” (Bagley, 75).