Mark Tobey was a leading painter of the Northwest School, one of the four "Northwest Mystics" described in a 1953 Life magazine article that proclaimed the "Mystic Painters of the Pacific Northwest." Tobey became renowned for an energetic, Eastern influenced "white writing" style of abstraction painted originally to express the frenetic pulse of New York City, a style which influenced Jackson Pollock among others. He was the first painter of the Northwest School to achieve international fame. Personally, he was an irritable, irascible man with many difficult relationships though also a few close friends. This biography of Mark Tobey is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

The Founding Rock

Mark George Tobey, once called the “Old Master of the Young American Painting,” is thought of as the founding rock of the Northwest School (Kunsthalle exhibition). In 1948, he gained international fame as the first American since James McNeill Whistler to be awarded First Prize in the prestigious Venice Biennale.

Tobey was the youngest of four children born to George Tobey, a carpenter and house builder, and Emma Cleveland Tobey. His mother was over 40 when he was born -- an occurrence far less common in the nineteenth century than in the twenty-first century. The Tobeys were devout Congregationalists. His father carved animals of red stone and sometimes drew animals for the young Tobey to cut out with scissors.

In later years, he told his friend Elizabeth Bayley Willis about interactions between his parents that left a lasting impression: "When he [Tobey's father] came home he would grab my mother and without even taking off his shoes, take her to bed. Then she would sit in her rocking chair and cry and cry and hold me in her arms and say he doesn't love me, all he wants is a woman" (Willis papers, 5-14).

Mark Tobey, Fashion Illustrator

Tobey dropped out of high school after his sophomore year to look for work because his father was ill. After a series of jobs that included work as an errand boy at a fashion studio in Chicago, he began to collect clippings by illustrators such as Charles Dana Gibson, creator of the Gibson Girl. At 21, Tobey moved to New York with dreams of becoming a fashion artist. He got a job at McCall's magazine.

Tobey spent half a dozen years in New York as a fashion illustrator. He applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship, and was rejected. "Some guy who painted green nudes got it," he later said (Wehr Personal Communication).

"Mark used to tell me how he once painted a wall for the editor of Vogue, which he felt would launch him as a mural painter -- that was what he wanted most to be known as -- and the place burned down and the wall was destroyed," Elizabeth Willis recalled (Willis Papers, 5-14).

He was 27, with a studio in Washington Square, when he had his first one-man show, at M. Knoedler and Co., in 1917. It consisted of charcoal portraits of celebrities. If the show was well received, no record has endured. He was not offered a second show.

The Baha'i Faith – Ideals For Life

The Knoedler show was organized by Marie Sterner, a portrait painter who introduced Tobey to the Baha'i World Faith at a gathering in Greenacre, Maine. Baha'i was founded in 1863 by Baha'u'llah, a Persian who urged world peace through a common faith and world brotherhood. Emphasis is placed on social-mindedness rather than theology or ritual. Baha'i has no priesthood or professional clergy. It teaches that no race or nation is superior; that all must enjoy equal opportunities and share equal responsibilities. Tobey embraced these ideals.

He became a fashionable portrait painter, and gained some small recognition drawing caricatures. That deftness is visible in Tobey's Market Sketches several of which were published in The New York Times, before he moved to Seattle in 1923, on the heels of a brief failed marriage. Years later, he told his friend Wesley Wehr (b. 1929) about the breakup of his marriage:

"We were sitting at the dinner table and she was carrying on about how I would have to give up my pretensions of being an artist, how I would have to give it all up and go out and find an honest job. I thought to myself, good God, I'm going to have to listen to this for the rest of my life! I got up from the table and went upstairs and packed my things. I came out to Seattle and checked into the Marne Hotel" ( The Eighth Lively Art).

He was guided to Seattle by George Brown, who had left the Northwest for New York to try to break into theater there. Brown told Tobey about the Cornish School of the Arts, promising that he would easily find a teaching job. Brown and Tobey traveled together on the train, sharing a bag of oranges that lasted them as far as Billings, Montana. As Wehr relates, shortly after he arrived in Seattle, Tobey's wife, having searched the New York apartments where she thought he might be hiding, discovered his whereabouts. She sent a box of his clothes topped with a copy of Rudyard Kipling's The Light That Failed.

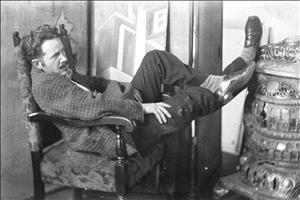

A Handsome, Restless Stranger

Tobey found a room in one of a row of small brown cottages on Spring Street, between 8th and 9th avenues. Betty Bowen, who came to know Tobey well, described the new arrival as "a handsome, restless stranger of 32, with blazing copper hair, a temperament to match, and no money" (Bowen). Viola Hansen Patterson, one of Tobey's early students, said, "He was full of tremendous energy, such energy he'd bowl you over -- Almost blow you out of the room. I did take three lessons with him, and then I caved in. It was too much for me. Tobey was extremely interested in one idea, the penetration of form free in space" (Callahan Papers, 1-5).

When Elizabeth Willis first inquired about Tobey as a teacher, Ann Nash, who studied with him at Cornish, told her: "I would not recommend him to you. He is a very difficult and unpredictable man. He is just as likely to forget that you are coming or to be out of sorts and tell you to go away. When you climb up the stairs you wonder if he is going to throw you back down the stairs" (Willis papers, 5-14). He charged students $1 a session but found it embarrassing to collect. When Willis began to study with him, he asked her to collect the fees in a basket at the end of each class.

Tobey's art horizons widened when he met Teng Kuei, a Chinese student at the University of Washington, who introduced him to Chinese brushwork. Four of Tobey's paintings were accepted in 1923 into the Ninth Annual Exhibition of the Seattle Fine Arts Society, a predecessor of the Seattle Art Museum (SAM), which would be launched a decade later (in June 1933).

Around the World

Tobey taught art classes at the Cornish School, and then spent 1925 and 1926 in Europe. In Paris, he met Gertrude Stein, and haunted the Louvre Museum. Spending the winter in France with American friends, the Sanders, he paid frequent visits to Chartres Cathedral. He traveled on to the Mediterranean, where he visited Baha'i shrines and became intrigued with the fluid forms of Persian and Arabic calligraphy.

When he returned to Seattle in 1927, he shared a studio in the ballroom of a house near the Cornish School with the teenaged artist Robert Bruce Inverarity, who was 20 years his junior. From a high school project of Inverarity's, Tobey became sufficiently interested in three-dimensional form to carve some 100 pieces of soap sculpture.

For the next three decades, Tobey was a veritable gypsy, constantly on the move from Seattle to New York, Chicago, England, and various countries in Europe.

In 1929, he was a juror for the Northwest Annual Exhibition. That year, he had the show that marked a change in his life: a solo exhibition at Romany Marie's Cafe Gallery in New York. Alfred Barr Jr., then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), saw the show and selected several pictures from it for inclusion in MoMA's Painting and Sculpture by Living Americans exhibition, which opened on December 2, 1930.

Eastern Influences

In 1931, Tobey sailed on the Britannia to England, to teach at Dartington Hall, in Devon. There, he was resident artist of the Elmhurst Progressive School. In addition to teaching, he painted frescoes for the school. He became a close friend of noted potter Bernard Leach, who was also on the faculty. Introduced by Tobey to Baha'i, Leach also became a convert. In 1934, they traveled together through France and Italy, then sailed from Naples to Hong Kong and Shanghai, where they parted company. Leach went on to Japan, while Tobey remained to visit Teng Kuei, his old friend from Seattle, before going on to Japan.

Japanese authorities confiscated and destroyed an edition of 31 drawings on wet paper that Tobey had brought with him from England to be published in Japan. No explanation for their destruction has been recorded; possibly they considered his sketches of nude men pornographic. Only a few sets remain in existence.

Tobey spent late June and early July in a Zen monastery outside Kyoto before returning to Seattle in the autumn of 1934. As quickly as it could be put together, he had an exhibition at the new Seattle Art Museum in Volunteer Park of portraits and watercolors done on his travels.

In 1935, he yo-yoed from New York to Washington, D.C.; to Alberta, Canada; back to England; and to Haifa, to visit the principal shrine of Baha'i. Sometime in November or December, at Dartington Hall, working at night, listening to the horses breathe in the field outside his window, he painted a series of three paintings, Broadway, Welcome Hero, and Broadway Norm, in the style that would come to be known as "white writing."

White Writing

Interlacing thousands of fine white lines made it possible to express the frenetic pulse of New York -- a task he found unapproachable with Renaissance techniques. No one, not even Tobey himself, had an immediate eureka! for the paintings. That would take a few more years. But he knew at once that he had achieved something special. Years later, he told an interviewer that white writing "appeared in my art the way flowers explode over the earth at a given time" (Kuh, p. 237). He said that even as a part of him was creating something new, another part of him was protesting the shift in his vision. He told columnist Louis Guzzo (1919-2013), speaking of the trip to China and Japan that preceded his breakthrough:

"It's been said I was searching for new techniques. Nothing of the sort. I was really enjoying myself, learning to do things that interested me. When I returned to England I was disturbed. I began to daub on a canvas and I was puzzled by the result. A few streaks of white, some blue streaks. Looked like a distorted nest. It bothered me. What I had learned in the Orient had affected me more than I realized. This was a new approach. I couldn't shake it off. So I had to absorb it before it consumed me. In a short time white writing emerged. I had a totally new conception of painting. The Orient has been the greatest influence of my life" (Guzzo)

Another source was at work too -- one less apparent to him at the time. Years later, looking at Willis's collection of ethnic textiles, he said:

"A painting should be a textile, a texture. That's enough! Perhaps I was influenced by my mother. She used to sew and sew. I can still see that needle going. Maybe that's what I'd rather do than anything with the brush-like stitching over and over and over, laying it in, going over, bringing it up. Bringing it up. That's what is difficult" (Willis papers, 5-14).

The War Keeps Him in Town

He was back in the Northwest for a few months in 1936, to teach in Tacoma, then back to Dartingon Hall to teach for the winter, returning again to Seattle in 1937. He had expected to continue teaching in England in 1938, but the mounting tensions of war building in Europe kept him in the United States.

Instead, he began to work on the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Art Project, under the supervision of Robert Inverarity, the young friend with whom he had shared a studio 11 years before. Inverarity had been named state director of the Federal Art Project Administration. Working in Seattle, Tobey met Morris Graves (1910-2001). One of the tasks of WPA artists was to paint murals in federal buildings. Tobey submitted a proposal for a mural for the front hall of the U.W. Chemistry Building. His proposal was rejected. Inverarity later did the mural himself.

In June 1939, Tobey attended a Baha'i summer school and overstayed his allotted vacation time. Inverarity dropped him from the WPA project. Fortunately, paintings he had done on the project were included in a WPA exhibition that August, where they were seen by Marian Willard, who operated an art gallery in New York.

Panned by Critics

Impressed with Tobey's work, Willard visited his studio, and bought his seminal painting Broadway. Willard did not care for the style of another of Tobey's paintings, titled Modal Tide. But in 1940, Modal Tide won the Katherine B. Baker Purchase Award of $100 in the 26th Northwest Annual Exhibition at Seattle Art Museum. The abstract painting flummoxed the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the Seattle Star, both of which ran a picture of the painting upside down. (Confusion about orientation struck again in 1968, when Tobey's painting Autumn Field was discovered to be hanging upside down outside President Lyndon Johnson's office in the White House.)

Humor columnist Doug Welch wrote in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that the painting looked like “an air-view of a week's washing, still in the basket." H. E. Jamison, art columnist for the Seattle Star, called it a monstrosity and wrote, "This insult to the $300,000 edifice wherein it hangs is done in dirty brown and resembles nothing so much as the crinkled bottom of a dried-up paint can or sun-baked mud flats" (both reviews appeared on October 11, 1940). One can imagine that such a reception poisoned any pleasure Tobey took in his prize.

Ignored and Distained in Seattle

Tobey issued a nicely printed announcement that he would accept a limited number of students for classes at 7:45 Tuesday and Friday evenings, in his studio at Room 203, 47252 University Way. "He got no response. No pupils. He was furious," Elizabeth Bayley Willis noted (Willis papers, 4-1).

In 1941, two of Tobey's paintings were accepted into the Northwest Annual Exhibition. When Welch showed up to tour the show, curator Kenneth Callahan followed him from room to room with an envelope to catch Welch's cigar ashes. Welch disdained the proffered envelope, choosing instead to flick his ashes onto the floor. Appraising Tobey's painting Form Follows the Man, which took second prize in oil painting, Welch described it as "a blizzard or a tangled bale of barbed wire, or chicken tracks across a salt flat" (Seattle P-I, October 14, 1941).

It is small wonder that Tobey felt unappreciated in Seattle. "I get terribly sick of so many uncultured and unmannerly people," he confided to his friend Elizabeth Willis (Tobey to Willis, February 25, 1944).

The Tobey-Graves Dispute, Part I

Tobey felt betrayed in November 1942, when Morris Graves's paintings were featured in a solo exhibition at the Willard Gallery in New York. (Willard was noted for her generosity in nurturing artists. The gallery had opened in 1936 as a rental gallery, to introduce contemporary art to a public not yet ready to buy it.) Graves was also exhibited in Americans 1942 at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York. Elizabeth Willis wrote:

"Suddenly Mark became Morris' most bitter enemy. We became aware of this at Mark's night classes. ‘He stole my stuff. Without my ideas he would be nothing. That is my technique. He never thought of white writing until he stole it from me. He used to come here night after night,’ Mark screamed. ‘Night after night, lie on the floor, ask me to show him my work, and pore over my paintings. Study them. Then stole them. Like a thief in the night.’ " (Willis papers 5-14).

Willis was a close friend to both Tobey and Graves. "Morris was writing him long letters begging to see him. I begged Mark to save them. Once or twice he read them to me before burning them" [(Willis Papers, 5-14). She writes, "I should have kept the lengthy letters Morris wrote to Tobey trying to patch up. I read them when I was so involved with Tobey that I was not allowed to see Morris any more. Mark was so jealous that a year went by without allowing Morris to speak to me" (Willis Papers, 5-14).

Superficial Forgiveness

Eventually things were patched up. Willis had dinner with Graves one evening in the University District, and then took him to Tobey's studio, where the two shook hands. The forgiveness, Willis notes, was superficial. "I am sorry to say that I have no use for his [Graves's] clever and unethical ways of reshaping, and literary titles for which he is I agree gifted," Tobey wrote to Willis (Willis Papers 5-3).

Willis wrote of Tobey’s jealousy and anger at Graves:

"When Mark found it impossible to paint [due to his personal life] he accused Morris, who was then painting luxuriantly, of being prolific. ‘Too many, too easy. He is a fake, a charlatan, a decorator, facile, skillful, easy, a copyist.’ He made me take down my Graves paintings when he came to visit. "How can you live with these evil birds? Morris is evil" (Willis papers 5-1)

Amusingly enough, Willis records that when Graves came to call, he conversely demanded that she remove the Tobey paintings from her walls.

Tobey took an equally dim view of Kenneth Callahan's work: "He paints to paint, and dashes them off. He's flat, no real form, no real structure" (Willis papers 5-7).

If Only I Had a New York Show...

Tobey was determined that his work would impress the New York art world as much as Graves's paintings had, if only he were given a proper exhibition. "Tobey pressed me and pressed me to go to New York and make him known," Elizabeth Willis recalls. "Morris and I tried so hard to make him known" (Willis papers 2-13). She got a job with Marian Willard for $35 a week. "In 1943, Tobey persuaded me to risk it and go to New York and get a job in a gallery. Tobey was unknown. It was hard to interest people at first in his work" (Statement dated April 3, 1955, Willis papers 1-2)

Willis remembers, "Marian Willard did not want a [Tobey] show, saying he didn't have enough things nor any one distinctive style, and that if he developed say on the lines of her smash hit man Graves, there might be a show" (Willis papers, 5-14).

In December 1943, Willard entered Tobey's Broadway in the Artists for Victory exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It won sixth prize, a purchase prize, which made the painting a part of the Metropolitan's permanent collection. (The African American painter Jacob Lawrence also won a Sixth Prize in the show). "Tobey was upset because she [Marian Willard] took her commission of one-third, and complained to me violently" (Willis papers, 6-1).

A New York Show

Wider recognition followed quickly. In 1944, just after Graves's second show at the Willard Gallery, Tobey had his first solo exhibition there. At age 54, he finally achieved a one-artist show of paintings in a New York gallery -- 27 years after his show of charcoal drawings at M. Knoedler and Co. Tobey fussed getting ready for the show, writing to Willis, "What with shipping and framing, I'll expect to owe Marian money when the show is over" (Willis Papers, 6-1). Prices were set for his paintings ranging from $125 to a top of $1,000 for E Pluribus Unum.

Willis persuaded Sidney Janis to write the foreword to the show's catalog. She also made a point of showing Tobey's work to artist Jackson Pollock, who found it intriguing. "Pollock studied Tobey's ’Bars and Flails, then did 'Blue Poles,'" Willis said, referring to the Pollock painting that made history when it was sold to the government of Australia for $2 million (Willis papers, 6-5). She notes that the source of Bars & Flails was a newspaper picture of Russian civilians executed on gallows by Germans.)

"Mark Tobey is almost certainly the man from whom Morris Graves got his ideas," a writer for Art News trumpeted. "Only Graves capitalized on them by turning them into pictures whereas Tobey has remained virtually in the calligraphy class" (Art News).

Maude Riley, reviewing the show for Art Digest, referred to Tobey's style as "white writing" -- a term Elizabeth Willis had earlier coined to describe it. The term stuck, being used forever after to describe Tobey's paintings.

"I named Broadway Norm," Willis recalls. "In fact I named practically all Tobey's paintings for him for many years. He used to save up a batch and get me to the studio and we would think up names" (Willis papers, 2-13).

Elizabeth Willis and Mark Tobey shared a romantic friendship which might have, but didn't, result in their marriage. Willis writes:

"After Mark's show he stayed in NYC a long time, and I walked with him over every street he had ever lived on, heard his entire past — the paintings stored by some hotel in lieu of rent owed them by the woman who had them. He asked me if I would marry him. I said yes, but wondered how it would ever work — he was so unpredictable, nervous, and both of us so poor."

The Tobey-Graves Dispute, Part II

She was persuaded by Morris Graves, and perhaps by her own common sense, to not marry Mark Tobey:

“He returned to Seattle, and when I came out in the Spring, I came back to Seattle. Mark had told his friends that he was going to marry me. I was quite delighted at the prospect, impractical as it was. Word got around. Several of Mark's old friends came to me and begged me not to marry him. I had anticipated this. Then Morris came, and begged me not to marry Mark. We had a long talk. I was shaken by what he had to say.“He said that I shouldn't marry Tobey, that it would be terribly dangerous for me to do so for reasons he could not disclose .... Finally I got up courage to go to Tobey's studio. He kissed me when I came in and said, 'I will have to learn this all over again.' Then he laid his head on my breast and sighed. I finally said, 'I can't marry you, Tobey.' He looked ghastly and said, 'Morris has poisoned you against me. I knew he would. I knew he would. He is speaking for himself, not me. We are two very different people' " (Willis Papers, 5-14).

Romany Marie had told Willis's fortune earlier that year, and told her that an older man needed her life and energy. Marie had said, "You must forgive him what he is and marry him." Tobey told her, " 'He has hurt me where it would hurt the deepest. First he has stolen my work. And now also you' " (Willis Papers, 5-14).

She did not regret her decision. "Mark was so terribly irritable and so ruthlessly cruel when he felt like being cruel. Once he said to me, 'If we marry we should never meet before noon.' Morris could not forgive him for his personal sloppiness, lack of bathing, dirty dishes. The bottles of sour milk all the way up the stairs to the studio. The deceits. The vanity" (Willis papers, 2-13). In memoirs written in September 1959, Willis notes that when Tobey moved from Seattle in 1954, he asked her to burn his old love letters and love poetry. She obliged, building a huge bonfire at her Edmonds home.

Over the next decade, Tobey developed white writing into a consistent style, reducing light to a shining entanglement of lines in which the world was charged with rhythmic vibrations. He pulled the intricate tracery of white lines back from the edges of the picture plane to leave the central image floating in space. "I was the first painter to leave the edges of my canvas untouched. The shape of a canvas can sometimes determine what's going on in it, and I didn't think that was wholly correct," he said (Newsweek).

Recognition

Josef Albers, who headed the Art Department at Yale University, invited Tobey to spend three months at Yale in 1951, as guest critic for art graduate students. It marked Tobey as one of the most respected artists in America. His star was in the ascendant that year. His paintings were included in major exhibitions at MoMA and the Whitney Museum. The California Palace of the Legion of Honor, where Elizabeth Willis had become acting assistant director, mounted a Tobey retrospective exhibition. Seattle-based Orbit Films made the film Mark Tobey: Artist, using Tobey's own script and piano music he had composed, played by Berthe Poncy Jacobson. The director was Robert G. Gardener, later head of the Film Center at Harvard University.

Tobey was by then living with Pehr Hallsten (who was always referred to simply as Pehr), whom he said he had met in 1940 when he enrolled in a French course at the Ballard Y.M.C.A. Alternatively, their meeting has been reported as having occurred when Pehr, a one-time worker for the Seattle Parks Department, was picking up trash with a stick at a local park. Both encounters may be true. In any case, they soon were inseparable. "Many friends think it's a homosexual relationship but it's not. He came and I need someone helpless to take care of. That is what my nature requires," Tobey told Elizabeth Willis (Willis papers, 5-14).

Both Tobey's teachers and his students had a habit of becoming his close friends. Beginning in 1949, when the teenage Wesley Wehr became his tutor in music composition, Wehr was a frequent visitor to Tobey's studio.

The Japanese Aesthetic

Tobey's companionship at home may have been Swedish, but his mind was turning more and more toward Japanese aesthetic. He became a close friend of Paul Horiuchi, who gave him a sumi brush and introduced him to painting with sumi ink. The emphasis on line and spontaneity was at the heart of the way Tobey liked to paint. The two often met at the home of George Tsutakawa, for evenings of painting and talk far into the night. John Matsudaira, a painter, or Tamotsu Takizaki, a Zen master and connoisseur of Japanese art, sometimes joined them. Tobey read Zen in the Art of Archery, applying its principles to painting.

Betty Bowen recalled that the wall of his studio "was spattered with black, and so were the floor and, often, his shoes" from his paintings in flung ink (Bowen). Tobey was awakening to an art form that was beginning to delight many forward thinkers in the U.S. art world. MoMA mounted the exhibition Abstract Japanese Calligraphy in the summer of 1954.

That appreciation, however, was not universal. After years of having two and sometimes three paintings accepted into the Northwest Annual Exhibition, Tobey submitted a sumi painting of a seated woman; a painting that Wehr recalls Tobey considered one of his best. It was rejected. Dr. Fuller reportedly was upset when he found out Tobey had been rejected. But all entries were anonymous, and the judges had not recognized Tobey's work in sumi style.

Marian Willard thought more highly of that phase of Tobey's work. He wrote to her that "for a white-writing artist I've turned into a black brush artist," adding, "My old friend Takizaki, to whom I owe much, says that the new work is something never seen before, even in Japan" (Willis papers, 5-14). Sumi paintings comprised his November 1957 exhibition at the Willard Gallery. Tobey became so steeped in Japanese aesthetic that he presented a paper titled "Japanese Traditions in American Art" at the Sixth National Conference of the U.S. Commission for UNESCO in San Francisco in 1957. (Tobey's paper was published in College Art Journal in the fall of 1958, and reprinted in Arts Review in 1962.)

George and Ayame Tsutakawa were frequent guests at his studio in the 1950s. Tobey would bring out his old collection of Japanese paintings, and they would discuss the brushstrokes and the spaces, talking for hours. George described the studio as a dense accumulation of musical instruments, art, and unusual objects, especially Asian objects.

Mark Tobey, Teacher

Tobey taught in his studio, by appointment. He was an important teacher to students such as Wehr and James Washington Jr. He also regularly rode the bus to Tacoma to teach an art class there, and came home with $40 for an afternoon's work. (Tobey never owned a car or learned to drive. He referred to the automobile as the "Queen of Death" on account of its fumes and fatal accidents.) He appears to have had the gift for helping students find their own strengths as painters.

James Washington described Tobey's preferred way of teaching:

"I'd bring paintings to him, and he'd study them. Sometimes, if there was something in the painting he didn't like, he'd block it out with his finger and ask me if the painting were better without the covered part. One time he thought a painting of a road into town lacked atmospheric perspective. He said, pointing at the painting, 'I want to go to town, and you won't let me go in. Do you want me to go, or don't you?' Sometimes he'd look at my painting and draw one of his own, as a result of looking at mine. 'This is the way I see your painting,' he'd say. I could see right away when something was wrong with mine. Tobey didn't look at a thing, he saw it through to the heart" (Hackett).

This way of teaching is instantly familiar to students in any of Japan's traditional arts.

Columnist Byron Fish interviewed Tobey and wrote of his teaching method:

"His idea of a good art class for beginners would be a field trip in which the pupils simply sit down and absorb sights, sounds, smells, and textures. He teaches a couple of art classes himself and makes no attempt to sift the students for talent. Whether they ever paint a good picture is unimportant compared to what they learn in the way of observing and aesthetic feeling" (The Seattle Times, May 21, 1951).

Helmi Juvonen's Obsession

Not all of those who cared for Tobey found their attentions welcome. Helmi Juvonen, a student whose work he praised, developed so serious a crush on him that she sometimes hid in the shrubbery outside his apartment building. When Tobey returned home at night he would hear a rustle of bushes and a soft, "Goodnight, Mark." At one point, she used to sit on an apple box outside the house in the University District where he was then living, telling anyone who passed, "A famous artist is in there, and he's being held prisoner by an art dealer" (Wehr Recollection).

When he decamped to New York, Helmi bombarded him with letters. She packaged a dead robin in a cake box and sent it to him as a present. At first Tobey was civil, perhaps even amused. But as her fixation on him intensified, he became exasperated. On May 25, 1954, he wrote from New York, "Dear Helmi, Please do not address any more letters to important museums or personages as such letters are detrimental to my work. I would prefer that you write me no more letters as I seldom read them and it is a waste of time and effort. Please consider this request. Sincerely, Mark Tobey" (Collection of Wesley Wehr). He refers to the fact that she had begun to write to museum heads and heads of state, asking them to help support Tobey so that she and he could marry.

A sample of her letters to him reads:

"Mon sweet Markie Honey, I loves you + want to a-cuddle up — so long since we have been together — am busy working on my (our) international exhibition — have enough temperas — will soon have enough sheckles [shekels] so we can mate-o together — thanks for last long loving letter — your poetry was a — pleasing — I know you love me — will pick you up in N.Y.C. soon. Pablo Picasso can be best man at our wedding" (Wesley Wehr Collection).

Tobey wrote to Willis, who was then in India: "Helmi, my eternal Ophelia, has been on the rampage. I went to a lawyer but no result. I tried to reason with her but no response. I hate to call the police" (Tobey to Willis. October 5, 1955, Willis papers, 5-10) It has been suggested that it was Helmi's insistent, unwanted attentions that caused Tobey to cease visiting the Northwest.

Difficult, Cold, Condescending, Copied

Tobey did not pretend to be pleasant with those whom he disliked. Graves found Tobey emotionally cold, as did artist Lubin Petric, whom Tobey alienated by cutting him dead in a social situation. Tobey offended William Cumming by offering through an intermediary to accept him as an apprentice in return for keeping his studio clean. Cumming declined.

Tobey's feelings toward Petric were likely related both to Petric's frequent inebriation and to the situation recollected by Richard Gilkey: "Any time Lubin Petric needed money, he'd just paint another 'Tobey' canvas." Gilkey identified Variations, a painting in the SAM collection attributed to Tobey, as having been done by Petric, since he recalled seeing it when it was still on Petric's easel. Petric was an impressively skilled painter with a flair for knocking out a picture in nearly any style he pleased. He left nothing of lasting importance, having never honed a distinctive style of his own. It could be said, however, that Petric was following another Asian tradition. Painting-by-emulation is a time-honored tradition in Asia, where copying the work of master artists is considered appropriate homage, and an important method of learning. There, as here, it sometimes is difficult for later generations to distinguish the work of student from master. It has been said that the principal reason Petric did not exhibit in galleries had to do with his fear of attracting the attention of the I.R.S. He filed an income tax return only once in his life. Use of an alias apparently did not occur to him. He could have used his birth name, Lubimir Petricich. (Recollections of the author; Lubin's nephew Russell Johnson; and William Cumming, in Sketchbook.)

Nonetheless Tobey was an important influence on Cumming, who listened when Tobey complained that tempera was an exasperating medium, because in order to define a plane, you have to edge it with a hairline to keep it from fading away. That idea blossomed into the contoured auras that surrounded the figures in Cumming's paintings for many years to come.

Tobey's Art Dealers

In November 1954, Tobey had a solo exhibition at the Otto Seligman Gallery. From then until his death, in 1966, Seligman was Tobey's Seattle dealer. "I do all transactions through his [Otto's] gallery," he wrote to Willis. "He is a fine person really and fighting hard for just an existence. I feel there is plenty of prejudice against him" (Willis papers, 5-9). The cause of the prejudice was unspecified. It may have been anti-Semitism, or resentment that he had "stolen" Tobey from the Seattle gallery owner Zoë Dusanne, who had formerly shown his work.

Marian Willard, who remained Tobey's representative in New York, saw to it that his paintings made regular appearances in the Whitney Museum's Annual exhibitions. She had begun to request that Tobey paint big canvases for his New York shows -- requests that angered Tobey. Elizabeth Willis recalled: "Tobey lived in fear of what she [Marian Willard] would say or do to his work. I felt that both he and Morris gradually deteriorated under the pressure to sell, to put out a new line each season like a new model car. Tobey said, 'I do not feel anything any more. All I do will sell, so I just keep on making the same thing'" (Willis papers, 2-13).

Jeanne Bucher introduced Tobey's work to Paris in March 1955, at her gallery on the boulevard Montparnasse. French critical acclaim surpassed any he ever received in the United States. He met Alice B. Toklas, who told him he had "penetrated perspective" (Rathbone). He liked the term so much that he adopted it as a description of what he was attempting in his work.

Poet Robert Sund recalled Tobey saying, "If I don't do anything else in my painting life, I will smash form." According to Sund, "Tobey described himself as 'writing a picture instead of building it up in the Renaissance tradition ... creating a sensation of mass by the interlacing of myriad independent lines. In their dynamic and in the timing I gave to the accents within the lines I attempted to create a world of finer substance' " (Sund).

Finally, They Love Him

In 1956, Tobey's paintings were part of the American Painting exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London, which introduced the budding American abstract style to England. Tobey hit the double jackpot, being elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters and receiving a Guggenheim International Award for Battle of the Lights.

In 1958, Patrick Heron wrote in Arts magazine: "Tobey is one of the most influential painters now living; he is the forerunner of Pollock, for instance in his 'shallow depth' system, as in the extreme evenness of emphasis in his overall composition -- two features of non-figurative pictorial expression which have spread first from Seattle to New York and thence all over the world." Earlier in the article, Heron dismissed Graves as a charming illustrator -- a touch that must have made Heron's praise even sweeter to Tobey.

The rave was echoed by the Los Angeles Times, which crowed, "Tobey has become the most famous of all living Pacific Coast painters." "Perhaps I should give up painting and spend what's left of my life teaching," Tobey mused in a letter to Willis. "I ran into Bernard Leach -- he's in England now -- thinks I would get along in Japan" (Tobey to Willis, January 20, 1958, Willis papers, 5-10)

In June 1958, just after he agreed to paint a mural for the Washington State Library in Olympia -- the mural, featuring abstract forms, was dedicated June 7, 1959 -- Tobey was awarded First Prize in the XXIX Venice Biennale, the art world's most prestigious recognition. His paintings had been included in the Biennale in prior years, but this was his first award. Fame made him no happier. "I wouldn't wish fame on a rat," he confided to Guy Anderson (Related to Wehr by Anderson).

Tobey Moves to Switzerland

In June 1960, Tobey moved to Basel, Switzerland, where he spent the rest of his life in a house at 69 Saint Albanvorstadt, where John Calvin had once lived. Tobey shared the house with Pehr and with Mark Ritter. The oven of an immense floor-to-ceiling Delft stove served as a storage bin for his paintings. Ernst Beyeler, Tobey's European art dealer, arranged for Tobey to live in the house cash free, in exchange for paintings, Wehr recalls. Tobey held the status of Niedergelassener, the Swiss designation for one who has all the rights of Swiss citizenship except the right to vote.

Andrea Gilbert wrote after a visit with him, "The house appeared as a massive villa, surrounded by a thick white wall." Inside, "A piano was almost indiscernible here beneath its covering of music and manuscripts and other pieces of paper. So were the floor and furniture. Five pairs of eyeglasses lay strewn on the floor in front of a cold fireplace" (The Seattle Times, January 24, 1971).

In a 1961 letter to Paul Horiuchi, Tobey wrote, "This move was not good for my work, I feel, and I only have one moderately big canvas to my credit." He also wrote that he was ill with an infection, and that he missed Paul and George Tsutakawa and hoped to get back to see them in June.

Retrospective at the Louvre

He called the 1961 retrospective exhibition of his work at the Louvre Museum in Paris "The biggest show of my life. Like taking my clothes off in public" (Newsweek, November 6, 1961). The show contained an astonishing three hundred paintings, spanning 50 years of his work, from his early tight, precise style to his newest work.

Tobey retained his Seattle studio, using it until the late 1960s during his annual summer visits. It was there that he painted the mural titled Journey of the Opera Star, commissioned by John Hauberg and Anne Gould Hauberg for the new Seattle Opera House. At 12-feet long and 7-feet high, it is the largest work he ever painted. Tobey was unhappy with its placement over the entry doors. "If I'm such a famous Washington painter, why is my only painting on public display so high no one can see it?" he grumped to Wesley Wehr (Wehr Recollection).

Retrospective at MoMA

In September 1962, Tobey won the brass ring of American art: a retrospective exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art. The show traveled to Chicago and Cleveland. Ironically, he was painting very little during this period.

Although he was celebrated as an abstract painter, Tobey never considered his pictures abstract. He spoke of seeing whole worlds in the bark of trees, or on pavements. "Pure abstraction for me would be a painting where one finds no correspondence to life -- an impossibility for me. I have sought a unified world in my work and use a movable vortex to achieve it" (Kuh). He spoke of "writing" a painting, creating it as a performance that "had to be achieved all at once or not at all -- the very opposite of building up as I had previously done" (Kuh, p. 24).

His health ebbed. "I have been ill all winter and have chronic bronchitis and heart not too good due to rheumatic fever at 22," he wrote to Willis. "I am very tired of galleries" (Tobey to Willis, November 4, 1966, Willis papers, 6-6).

Katherine Kuh, who visited Tobey in 1971, spoke of walking with him to the Kunstmuseum in Basel: "Before I knew what had happened, he was sitting on the pavement, caressing a small wounded bird that was lying there terrified and limp. He crooned to it and finally having picked it up, smoothed its feathers gently as he reassured the tiny creature. After some coaxing, the bird established itself on the lower limb of a nearby tree" (Kuh, Saturday Review World, September 11, 1973).

Curmudgeonly Ways

In his latter days, Tobey regarded Seattle with bitterness. "He used to rave and rant about how much he did to make Seattle famous," Willis noted. "He had made it known throughout the world for its art movement. Seattle infuriated him as it never really appreciated him or paid him adequate homage. For years he ranted 'If they really appreciate me, why don't they build me a studio? Offer me a studio?" (Willis papers, 6-5).

Art patron John Hauberg did just that, but Tobey declined. In 1971, Hauberg wrote to Tobey proposing the establishment of a Tobey Museum near Seattle, in a place with some acreage around it -- the place where Pilchuck Glass School was later established. Hauberg proposed to hire Tobey as a consultant, paying him $1,000 a month, and said they also wanted to buy paintings for the museum. He told Tobey he had taken an option on a house at the corner of 14th Avenue and East John Street in Seattle, with a cottage in the garden, where he would be pleased to have Tobey live. Tobey preferred to stay in Basel.

Knowing Tobey's anxiety that he could be left impoverished in old age, Hauberg offered to send Tobey $1,500 per month for life, in exchange for his agreement to bequeath his estate to the Seattle Art Museum. (Curiously, Hauberg knew nothing about the stipend Dr. Richard Fuller had begun for Tobey in the early 1940s, as credit toward paintings acquired for SAM.) Seattle attorney Arthur Barnett traveled to Basel to draw up the will, which was handwritten by Virginia Barnett and signed on each page by both Barnetts and by Tobey.

Barnett was not Tobey's accountant, as has sometimes been reported -- he was solely his attorney. He did, however, prepare Tobey's U.S. income tax returns through Seattle accountant John Polk, whom Tobey paid with drawings and paintings. Preparing Tobey's U.S. income tax returns was no easy task, since requests to Tobey for information about his U.S. sales went largely unanswered. "Tobey mostly tore them up," Hauberg says. "He grew to resent Barnett's intrusion into his dealings. Tobey became a wretched old man, paranoid, and terribly self-centered. He thought everybody owed him something."

Tobey customarily kept a shoe box on his piano in which he stashed money. When a friend asked for a loan, the money came from the shoe box. "He came to believe everybody owed him money taken from that shoe box on the piano," Hauberg says (Deloris Tarzan Ament Interview with John Hauberg, February 8, 2000).

After he had signed the will, Tobey told Ritter that he realized it gave too much power to Barnett as executor, and left nothing to Ritter or to Baha'i. Tobey began a second will, to divide his estate, but said he found it too complicated. Instead, his later will simply left everything to Ritter, asking him to distribute things as he knew Tobey would have wished. Tobey continued to cash Hauberg's monthly checks, making no mention of the fact that he had drawn up another will.

IRS Victory for Artists

Tobey won a significant victory in a battle with the Internal Revenue Service in May 1973. The agency had levied deficiency assessments against him for 1965 and 1966, saying he was not entitled to the $25,000 yearly tax deduction granted to other U.S. citizens earning income outside the country.

The I.R.S. contended that Tobey's paintings were "manufactured products," and thus constituted a sale of property rather than earned income such as he might earn from employment. Tobey challenged the assessment. A Tax Court judge in Washington, D.C., Howard Dawson, ruled that Tobey was entitled to the exemption. The ruling helped not only Tobey, but other artists and writers working abroad who were affected by similar I.R.S. deficiency assessments (The Seattle Times, May 21, 1973).

Mark Tobey's Death and Subsequent Legal Battles

Tobey died in Basel on April 24, 1976, leaving a messy legal battle to be fought over his contradictory wills. Arthur and Virginia Barnett, who were in Europe at the time of his death, traveled to Basel to attend a Baha'i funeral service for him at St. Alban Church in the old quarter of Basel. Virginia spoke a eulogy, saying in part:

"He loved to talk about the meaning of life, and he loved to play. As he walked, hands behind his back, along the streets and through the markets in Seattle, he was always observing, absorbing, relishing. He saw and felt in great scope, and what he may have selected to remember in detail was a bit of lichen on a stone or a glossy spot of cherry bark on a tree trunk. He was touchingly human, vulnerable, tender, proud, irascible, forgiving — and in my view, a ranking creative genius of this century (Barnett).

Many of the estate's assets were devoured by legal fees. Hauberg entered suit against the estate in the amount of $88,750 for monthly payments to Tobey begun in February 1971. The estate was settled in 1977, with assets divided among Ritter, SAM, and two of Tobey's nieces. The museum received the contents of Tobey's Seattle studio -- largely personal effects.

Tobey's dreams about painting may best be summed up by something he once said: "If you could sign your name to moonlight -- that is the thing!" (Bowen).