McNeil Island, located in southern Puget Sound, was named in 1841 by Lt. Charles Wilkes of the United States Exploring Expedition in honor of William Henry McNeill. McNeill (the name, but not the island, is spelled with two l's) was captain of the Hudson’s Bay Company steamship Beaver, the first steamship to travel on Puget Sound. In 1875, Washington Territory’s first federal penitentiary began operation there. The federal government turned McNeil Island over to the Washington State Department of Corrections in 1981. It has the distinction of being the only prison in the U. S. that began as a territorial prison, became a federal penitentiary, and finally a state prison. It is also the last prison in America located on a small, remote island. McNeil Island, in Pierce County, is 2.25 miles wide and 3 miles long. It comprises approximately 4,400 acres, and lies 2.8 miles across Puget Sound from Steilacoom, the nearest town.

Early Days on Puget's Sound

In the spring of 1841, the United States Exploring Expedition under the command of Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (1798-1877) entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca and sailed south into Puget Sound.

On May 11, 1841, Lt. Wilkes anchored his sailing ship Porpoise in southern Puget Sound near Fort Nisqually, a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, and was soon visited by Alexander Caulfield Anderson (1814-1884), the post’s Chief Trader, and William Henry McNeill, captain of the company’s steamship, Beaver.

Lt. Wilkes stated in his diary: "They gave me a warm welcome and offered every assistance in their power to aid me in my operations." In appreciation, Wilkes named the two large islands just north of Fort Nisqually, Anderson Island and McNeil’s Island. Lt. Wilkes misspelled McNeill’s name, dropping one l, and eventually the possessive was eliminated.

William Henry McNeill (1803-1875) was the Captain of the brig Lama which in 1830 sailed from Boston, 12,000 miles, around Cape Horn, to the Pacific Northwest on a fur trading expedition. Boston merchants owned the brig whose cargo consisted of trading merchandise. The Hudson's Bay Company purchased the Lama and its cargo and retained McNeill as captain. In order to work for the Company, he was required to become a British citizen. In 1836, the Hudson’s Bay Company vessel Beaver, the first steamship on Puget Sound, arrived at Fort Vancouver. William McNeill took over as the Beaver’s Captain and remained so until 1851. Captain McNeill retired from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1861, retiring to his farm on Vancouver Island near Victoria, British Columbia. He died of pneumonia on September 4, 1875.

Steilacoom

Steilacoom, home to the ancestral tribe of that name, was the nearest settlement to McNeil Island. It was settled in 1851 by Lafayette Balch. Located between Olympia and Commencement Bay (later Tacoma), Steilacoom was, for a time, the largest town in the territory. It started with a general store and trading center in direct competition with the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Nisqually. By 1852, the town had the first post office on Puget Sound and soon had a pharmacy, brewery, barrel factory, salmon-packing plant, three sawmills, and a burgeoning shipbuilding industry.

Steilacoom’s main source of commercial prosperity was the manufacture and export of lumber to San Francisco. When Congress established the Territory of Washington on March 2, 1853, Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) chose Steilacoom to be the seat of Pierce County. The first census of the Washington Territory taken in 1853 showed a total settler population of 3,965; Pierce County’s population was only 513.

Settlers on McNeil Island

The first documented settlers on McNeil Island were the Meeker family, Washington pioneers who came west across the Oregon Trail. In the spring of 1853, Ezra Meeker (1830-1928) and his brother Oliver spent several weeks exploring the Puget Sound region, looking for suitable land to homestead. In June 1853, they decided to settle on McNeil Island.

The Meekers established their homestead on the east shore across from Steilacoom, on the future site of the Territorial Prison. The island had an abundance of building materials and soil adequate for farming, but it was remote, three miles across Puget Sound by rowboat to Steilacoom. Supplies were hard to obtain and the Meeker’s social life was nonexistent. After about a year, Ezra Meeker moved his family to Steilacoom and became a merchant.

The First Prison

In 1855, the Legislative Assembly decided that Washington Territory needed a penitentiary and established a commission to find an appropriate site. Due to political bickering and the Civil War, the project was neglected until 1867 when the U. S. Congress authorized a prison for Washington along with $20,000 for the building project. Two sites considered were Fort Vancouver to the south and Port Townsend to the north. Steilacoom, a growing industrious community with a busy seaport, was located in the middle and was chosen by the legislature to be the site for the new prison.

But there was a problem. The Puget Sound Agricultural Company claimed all the land in the area and refused to grant or sell any for a prison, so the penitentiary commission began to look at the nearby vacant islands.

In 1870, Jay Emmons Smith, the current owner of the former Meeker homestead, offered to donate 27 acres of his holdings along the shoreline, to the penitentiary commission. They gladly accepted Smith’s gift and completed the transaction on September 11, 1870, giving him $100 to "bind the deed." After 15 years, the search for a prison site was finally over. It proved to be a shrewd deal for Smith. He went to work for the penitentiary as a guard and the value of his adjacent property increased.

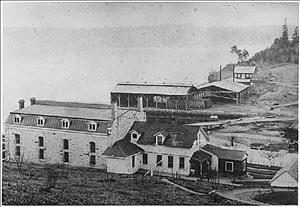

The contract to build the first cellhouse, according to plans submitted by the Attorney General, was given to Isaac C. Ellis of Olympia. Construction began in 1871 and was scheduled for completion by November 1873. The building was a large brick and stone shell with back-to-back cells, none against an outer wall, to prevent escapes. The interior cellblock held 48 double cells, three tiers high. Each cell measured six by eight feet, with a seven-and-a-half-foot ceiling. However, there was one astonishing omission. The prison had no auxiliary facilities; no kitchen, bathrooms, offices, or accommodations for the guards, and there was no provision for water or heat. The facility was finished on time, but it was virtually unusable.

Edward S. Kearney, the U. S. Marshal in charge of the prison, asked the Attorney General for an additional appropriation to build a structure for the guards and for furnishings for the cells and guardhouse. The addition, built by Benjamin Harned of Olympia, was a wood frame one-and-a-half-story structure built against the end of the cellblock, enclosing the only exterior door. Although the prison became functional, it had the effect of turning the fireproof stone building into a firetrap. The guardhouse was replaced in 1898, using bricks made by the prisoners.

The First Prisoners

The Washington Territorial Penitentiary officially began operations on May 28, 1875, when Marshal Kearney arrived with three prisoners: Abraham Gervais, age 28, sentenced to 20 months for selling whisky to Indians, Frank Lafontaisis, age 27, sentenced to 18 months for the same offense, and John W. Hand, age 28, sentenced to 12 months for robbing a store at Fort Walla Walla.

After being logged in the daily journal by the guard on duty, the only admission procedure, the prisoners were issued black and white striped prison garb and promptly put to work cleaning up and grading the prison yard. Marshal Kearney required prisoners to work all day, every day, except Sunday. Prisoners were provided with only the basics, necessary work clothes and food. In order to make money for extras, like tobacco, soap, and matches, prisoners were allowed to make cedar shingles. The shingles were sold in Steilacoom, and the net profits went into a prisoner’s fund used to buy those extras for the inmates.

Initially, the prison operated with a staff of three guards, appointed by the U. S. Marshal. They were paid $75 a month to live at the penitentiary and were on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The government allowed each guard two and a half days off each month to visit his family on the mainland. Although no charge was made for the bed, the guards were expected to supply and prepare their own food.

Although prisoners were usually transported among Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, and Port Townsend by steamboat, until 1882, most of the trips to and from McNeil Island were by rowboat, a slow, awkward, and sometimes dangerous trip. Marshal Charles Hopkins hired Neil O. Henly (1855-1944) as a prison guard. He was a seasoned sailor and boat builder, and shortly after coming to the island, decided to design and build a sailboat for the prison. With the help of two experienced prisoners, Henly built a 24-foot sloop that made mail and supply runs to Steilacoom much faster, easier, and safer.

By the early 1880s, the first settlers had established themselves on McNeil Island. There were 15 landowners living on small farms. But, in order to make a decent living, most of the men engaged in outside work. By the turn of the century, the thriving community had a small general store, brickyard, lumber company, small library, schools, two post offices and a cemetery.

From Territorial Prison to Federal Penitentiary

In 1889, Washington became the 42nd state, and Republicans elected Elisha Ferry (1825-1895) its first governor. In July 1890, the Attorney General, responsible for directing federal prisons, formally offered the penitentiary to Governor Ferry. The gift was declined with the explanation that permission from the legislature was required before the state could assume responsibility for the prison. However, the Washington State Legislature never took action and the facility remained in federal hands. The name was changed from the Washington Territorial Prison to McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary. The Attorney General neglected the prison shamefully, perhaps because it was out of the way and communications were difficult. Improvements were slow in coming. In 1906, after 31 years of operation, a prison hospital was built with a $5,000 appropriation from Congress and the help of prison labor. The Attorney General also authorized hiring a resident physician for $128 per month and board. The hospital was razed and rebuilt in 1926 and expanded in the 1930’s with two new wings.

Between 1906 and 1930, three additional cell houses were built. Cell house No. 2, completed in 1911, contained 66 double cells; cell house No. 3, completed in 1924, contained 50 eight-man cells; cell house No. 4, completed in 1930, contained 30 eight-man cells.. During this same period, the penitentiary added an administration building, new hospital, auditorium, kitchen, and dining hall. By the 1930s, the penitentiary population hovered around 1,000 inmates.

In 1911, an electrical generating power plant was constructed and electric lights installed in the prison’s buildings and cells. A new and bigger power plant was constructed at a different location in 1929.

The prison finally constructed a shipyard building in 1911, where Captain Neil Henly built the their first powerboat, the John G. Sargent, a 46-foot launch that served the institution for 50 years. Prior to this, boats were built and maintained under a large piece of stretched canvas near the beach.

The telephone, invented in 1875, did not arrive at McNeil Island until 1923, and then, it was one telephone line serving nine parties. Island residents had to pay to use the phone at the general store. The first dial phone did not arrive on the island until 1934, and there was no phone service to the prison employee’s private residences until June 1957.

Although they had been supplementing their food supply with farming since the early days, in 1926 the Attorney General authorized the penitentiary to develop a 360-acre self-contained farm colony. By 1933, the honor farm had its own housing for 200 inmates and all the necessary buildings and equipment for livestock and a dairy operation.

Enter the Federal Bureau of Prisons

In 1929, Congress finally established the Federal Bureau of Prisons, mandated to centrally coordinate the administration of the federal prison system. Prison wardens, used to operating independently, didn’t take kindly to the new imposed bureaucracy. Many adjustments in supervisory personnel had to be made for the new prison system to run smoothly. In addition, the U. S. Public Health Service was authorized to provide medical services to federal prisons.

The Federal Prison Industries (FPI) was incorporated in 1934 as a wholly owned enterprise of the government. The FPI ran more than 30 types of industrial operations. The products were sold only to other government agencies and were not in competition with private enterprise on the open market. The intent was to provide employment and vocational training, as well as income, for federal inmates. Profits were used to pay prisoners’ hourly wages plus monetary awards for performance and good conduct. The money was usually held until the prisoner’s release or given to needy family members.

Between 1925 and 1936, the government purchased all the privately owned land and civilians moved off the island. McNeil Island became the largest prison reservation in the United States. The Bureau of Prisons appropriated additional funds to move the bodies of 86 pioneers off the island, to cemeteries of the families' choice.

Water Works

During the early years, sewage was just dumped onto the shoreline. Eventually, the penitentiary installed a pipe to discharge sewage directly into Puget Sound. The prison's biggest problem was the water supply. Wells and springs were inadequate and unreliable. Prisoners were detailed every day to pump water by hand into a reservoir on top of the cellblock. Bathing facilities consisted of water heated in a barrel with hot bricks. When the water supply ran low, prisoners bathed in the frigid salt water of Puget Sound.

In 1936, work was begun to finally solve the water supply problem by damming Eden Creek, creating a substantial reservoir named Butterworth Lake, and piping water to the prison. With the addition of a water filtration plant built the previous year, the penitentiary now had its own adequate water supply system.

War Years and After

During World War II (1940-1945), the McNeil Island Penitentiary was enlisted to help in the war effort. In January 1942, Federal Prison Industries began operating a shipbuilding plant, which built three 64-foot wooden tugboats used by the Army Transport Service for towing barges loaded with equipment and supplies to military bases in Alaska. The Federal Prison Industries also built a cannery, which supplied fruits and vegetables to the military and the prison. The cannery was phased out in 1958 due to a decreasing demand for cannery workers in the civilian labor market.

In 1948, the honor farm at McNeil Island was designated as an official Federal Work Camp, used for nonviolent first offenders and prisoners with sentences of one year or less, and a separate institution from the penitentiary. Eventually, more than 1,000 minimum-custody inmates were living in the camp providing the manpower, skills, and trades needed to operate and maintain the island. In addition, the inmates raised their own chicken, beef, and pork; operated a dairy; maintained a huge poultry house; grew potatoes, carrots, beans, and cabbage; and ran an apple orchard. The camp was almost a self-contained small urban community.

Although McNeil Island was never more than a “medium security” prison, over the years the penitentiary housed several prisoners well known to the public. The most notable inmates were Robert Stroud, known as “The Bird Man of Alcatraz”; Roy Gardner, a notorious train robber; Alvin Karpis, gangster in league with the “Ma Barker Gang”; Frederick Emerson Peters, a notorious swindler and impersonator; Roy Olmstead, king of the Puget Sound bootleggers; Mickey Cohen, called by Time Magazine “the undisputed boss of Los Angeles gangdom”; Charles Manson, responsible for the Sharon Tate murders; and Dave Beck, Seattle labor leader.

End of the Federal Era

Even though McNeil Island operated as a modern institution, in 1976 the Bureau of Prisons decided to phase out the 107-year-old federal penitentiary, declaring it "obsolete" -- too big, too old, too remote, and too expensive to maintain and renovate. The trend was toward smaller, more manageable prisons, housing no more than 500 inmates.

By 1979, the shutdown operation was in full swing. At the Federal Work Camp, the beef and dairy herds were moved to the Federal Correctional Institution at Lompoc, California, and the rest of the livestock was sold. The Federal Prison Industries shops and equipment were moved to other federal institutions.

In 1980, at the request of Senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989), the Bureau of Prisons agreed not to further dismantle the penitentiary. Washington state wanted to use the facility temporarily, to help relieve overcrowding in the state’s institutions. In February 1981, Governor John D. Spellman (b. 1926) negotiated a contract with the General Services Administration to lease the prison for three years, with two one year extensions permitted, for $350,000 a year.

In March 1981, the last of the federal prisoners were transferred out and the first state prisoners moved into the penitentiary. Control of McNeil Island was formally turned over to Washington State Department of Corrections on July 1, 1981.