The Northwest painter Neil Meitzler is best known for paintings in which broad sweeps of aqueous color are overlaid with flung, spattered, and blotted paint to create lively surfaces in representations of mountain rocks and waterfalls. A soft-spoken man, he showed his emotional depth most clearly in such brooding landscapes. From 1957 to 1977, he was a designer at the Seattle Art Museum (SAM). He left the Pacific Northwest in the late 1970s, returning to Walla Walla in 1989. His life has been split between a gay lifestyle and a Seventh Day Adventist upbringing and influence. Neil Meitzler died of pancreatic cancer in Walla Walla in February 2009. This biography is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

Note: All unattributed quotations are from Deloris Tarzan Ament's interview with Neil Meitzler on June 12, 1999.

Critical Moves

Although both his mountain waterfalls and his later giant botanical paintings might have lent themselves handsomely to public commissions, Meitzler left the Northwest at a critical point in his career, and at a time that marked the beginning of the boom in public and corporate commissions. When he returned in 1989, it was to Walla Walla, from which it was difficult to reestablish his reputation among a young, new generation of collectors and gallery owners.

He was born Herbert Neil Claussen, on September 14, 1930, in Pueblo, Colorado. When he was five years old, the family moved to Albany, Oregon. Growing up there, he alternated between wanting to be an artist and a Seventh Day Adventist preacher. He got ample drawing practice: To keep him pacified during meetings, his mother gave him crayons and paper.

He was nine when his father died of Hodgkin's disease. When his mother remarried two years later, Neil and his two younger sisters began to use their stepfather's last name, Meitzler, although no formal adoption was ever registered. When Neil was 12, the family moved to the small town of Orting, in Pierce County, Washington, where he attended high school and helped in the greenhouse his parents ran.

A Gay Teen

He dropped out of school at age 17, after his stepfather beat him in front of the rest of the family, wrongly accusing him of having molested one of his sisters. Neil's mother gave him $20 to enable him to leave home. Having no safe place to go, he headed for Seattle, the nearest big city. All-night movie theaters provided a place to sleep. He had already realized he was gay, and almost immediately caught the eyes of gay cruisers.

When he was arrested, along with several other gay men, it never occurred to him to deny what he was accused of. He had been claiming to be 18, and he continued that fiction under arrest, which meant he was booked as an adult rather than as a juvenile, as he properly should have been. The arrest record that followed him through life prevented him from serving in the military during the Korean conflict, and from being hired for several jobs for which he was well qualified.

It may be that his early experience with the law left him sufficiently shaken to decide to forsake being gay. He married at 21, and took a job as a draftsman at Boeing, where, in 1952, one of his paintings done in what he calls "beginner's blue" won first prize in an employee art show. "It was a bad show, but it meant a lot to me then. It was the shot in the arm that started me in the right direction" (Robbins).

Encouraged by the win, he had a show at Hathaway House, a small gift shop near the Frederick & Nelson department store. Art critic John Voorhees reviewed the show favorably, and three paintings were sold. His career was launched.

Homophobic Interventions

By that time, he was beginning to have marital trouble. He went for counseling to a Seventh Day Adventist pastor, who advised him that the best remedy for homosexual yearnings was to be castrated. When the same sage advised Meitzler's wife that he would doubtless molest their young son, his wife left him.

Meitzler returned to gay life.

In 1954, when he was painting sets for Dorothy Fisher's dance recitals, he met Kenneth Callahan (1906-1986) at a party at Fisher's studio. Callahan soon became his teacher and mentor. The system was that Meitzler would paint in his own studio, then take the results to Callahan for criticism. "Sometimes he wouldn't say anything. Those were the worst times."

Those times were mercifully few. "I learned from him what real painting was about," Meitzler said. "I knew techniques and materials, but I had to learn from him what art really is. He taught me design and painterly qualities. He saved me a lifetime of searching" (Robbins).

Callahan also taught him to beware of self-imitation. "It's awfully easy to imitate yourself," Meitzler said. "To copy yourself is the worst kind of illustration." He in turn taught Callahan a trick used to add texture and depth in scene painting -- lifting off paint while it is still wet by blotting with crumpled cloth or paper. Callahan used the technique extensively, particularly in paintings done near the end of his career.

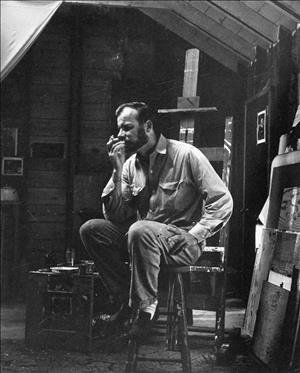

In the 1950s, much of Meitzler's work, like Callahan's own, was figurative. Their personalities meshed so amicably that Meitzler built a studio cabin near Callahan's on the south fork of the Stillaguamish River, near Granite Falls. A 1957 ink portrait he drew of Callahan while they were hiking together in the Cascades is part of the Seattle Art Museum's permanent collection.

Morris Graves Opens a Door

Meitzler was house-sitting for the Callahans for a few weeks in 1957 when he was picked up by Morris Graves. Graves was at that time on bad terms with Callahan, who disapproved of his gay lifestyle. Meitzler didn't know that background when he invited Graves to "come home" with him. Reportedly, it amused Graves greatly to exercise himself in Callahan's house.

While he was there, he saw some of Meitzler's paintings, and complimented his work. He asked to borrow several pieces. Taking them home, he set them in prominent spots and invited SAM director Dr. Richard Fuller (1897-1976) and his wife to dinner. When Dr. Fuller took favorable notice of the borrowed paintings, Graves persuaded him to hire Meitzler for the staff of SAM.

Meitzler hired on for $300 a month, in September 1957, taking a pay cut to accept. He had been earning $500 a month running the Dance Shop, selling costumes and dance supplies. He became one of three museum installers, along with Allen Wilcox (who was also a painter), and Ernie Dietrich. Meitzler's official title became Designer after he'd been at the museum for a few years.

Meitzler won the Katherine Baker Purchase Award in the 1958 Northwest Annual Exhibition for Mountain Stream, a casein painting that, thanks to the purchase award, is in the museum's collection. "Getting into the Northwest Annual was the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for an artist," he said. "It meant you had arrived, and could be taken seriously." Winning an award signaled that an artist was among the region's best. That same year, his painting Winter Garden won an award in the Northwest Watercolor Society's 18th Annual Exhibition, which in those years was held at SAM.

The Politics of Painting Prizes

Meitzler learned an important lesson about the Northwest Annual. Otto Seligman, whose gallery represented Mark Tobey (1890-1976), brought in a painting judges perceived as "smudgy and third-rate" to enter in the Annual. No one knows what led him to make that choice, but Wesley Wehr, a close friend of Tobey's, recalls that Tobey took great pride in the piece -- a seated nude painted in sumi ink.

The show was judged by a committee of four or sometimes five jurors appointed each year by Dr. Fuller. Someone from the University of Washington art faculty was always a juror, and Callahan often was a part of it. No woman was ever appointed.

The system was that "the boys" (Neil, Ernie, and Allan) would bring up the entries one by one, and each juror voted either to accept or reject it. In theory, the artists were anonymous, although artists' styles tend to be so distinctive that in the small Northwest art community, a high proportion of the paintings could be identified with confidence as having come from a particular artist.

On this occasion, none of the jurors recognized the smudged painting as having come from Tobey. All of them voted to reject it.

Dr. Fuller became very upset that "the boys" hadn't shown him that it was by Tobey. "He thought it was important for people to see what the region's major artists were doing each year, whether it was good or bad," Meitzler explained. That was not, however, the premise on which the Annual operated. It was presumed to show the region's best paintings, regardless of who created them.

Meitzler made his own contribution to the organization of the Annual when the number of entries, which increased each year, reached the stage of making the old method of choosing by elimination unrealistically time-consuming. Over the years, the system had progressed to setting all the entries on the floor, leaned against the wall. Each juror placed slips of colored paper in front of paintings he voted to eliminate. Meitzler convinced Dr. Fuller that selection would be faster and fairer if jurors instead voted for paintings they wanted to include, rather than exclude. That system was adopted, and proved to be both faster and more beneficent.

Meitzler also gave a boost to the career of William Cumming. (b. 1917). Cumming struggled with tuberculosis, and first went into the Firland Sanatorium (north of Seattle) in 1942. Some time around 1958, when he emerged from another stay at Firland, he did a series of drawings on newsprint and on the pages of books. Meitzler convinced SAM's assistant director, Millard Rogers, that Cumming was an artist to be taken seriously.

Brightness and Sunlight

In 1960, Meitzler took several months' leave to spend time in Greece, primarily on the island of Mykonos. Beautiful as the experience was, he reported, "I found it difficult to paint. There was too much brightness and sunlight." Accustomed to subdued Northwest light, he was satisfied only with a painting that he completed in the muted light inside a church.

A painting from his Greek series, Procession, Mykonos, was purchased for SAM's permanent collection in 1960. It is one of the few paintings Meitzler ever did that reflect a specific time and place. Like many of his early paintings, it is done in casein on rice paper, mounted on board.

Casein, which creates a chalky surface, was the medium also preferred by Tobey and Graves. Like them, Meitzler relied heavily on the use of gray and white. He once said, not entirely facetiously, "Any painting will sell if it has enough white in it."

Seattle Art Museum's Asian Influence

Spending his days intimately involved with the art at the Seattle Art Museum, Meitzler had ample opportunity to study Asian brushwork, which he emulated in his own paintings. His spatter-fleck way of bringing life to a long, unbroken brush curve of waterfall is taken directly from sumi technique.

Similarly, influenced by scroll paintings in the museum's collection, he painted landscapes on a series of five hand-scrolls, one of which is in the SAM collection. Completed in 1961, they all bear the same title: Journey. (Meitzler gave one of the five scrolls to his grandfather, and it is lost. Three others are in the collections of Joanna Eckstein, Norman Davis, and this writer, Deloris Tarzan Ament.)

In 1970, he first exhibited a new direction in his work: shaped canvases. "It's easy to do beautiful pictures," he said. "Too easy." He exhibited a series that broke out of the framed format, incorporating chunks of adhered wood to give a sculptural dimension to landscapes. "I want viewers to be aware of the materials first, and then the material should fade into the whole," he said at the time. "I think of my paintings as landscapes, almost sentimental and traditional, achieved through materials that bring dimension to the work" (Vorhees).

A painting from that series, River Rocks Becoming Islands, is in the collection of SAM. The wood surface is plywood, found on the river near his Granite Falls cabin.

Remarriage and Redivorce

Following an emotional reunion with his son, Meitzler remarried. In order to break completely with his former life and companions, he left his job at the museum in September 1977 and moved to the East Coast to work as a printer for the Seventh Day Adventist Church presses in New Hampshire, Georgia, and Maryland, successively. He returned to the Northwest at the time of his divorce, in June 1989.

In order to be near one of his children, he chose to live in Walla Walla. There he continued to paint until his death on February 21, 2009, although he exhibited infrequently. He was survived by his longtime companion, Ikune Sawada (b. 1936), a painter, master gardener, and bonsai artist.

In Walla Walla, nature, and particularly rivers and mountain gorges, continued to inspire Neil Meitzler's work. This was not now the landscape in which he lived, but the remembered landscape of Western Washington.

As he described it, "Sunlight filters through haze. There are no shadows. Colors are flattened and cooled" (Robbins). The walls of his basement studio are papered with heroic landscapes. Canvases depicting giant blossoms spread under banks of fluorescent lights. River gorges sluice through mountain landscapes.

His paintings not only reflect Northwest light, they literally are shaped by it.