Lewis County in southwest Washington can truly be called the “mother of counties.” Half of the present-day Washington and of British Columbia were carved from its original borders. But the county’s location astride the Cowlitz Trail between the Columbia River and Puget Sound meant that communities with good water access would develop first. The construction of the transcontinental railroad in the 1870s and innovations in logging technology were the major spurs to settlement.

First Peoples

Native Americans calling themselves Chehalis and Meshall lived along the banks of the Chehalis River and spoke a language which was related to the Salish languages of Puget Sound and the Pacific Coast. Cloquallum Creek generally represented the division between the Lower Chehalis and the five bands of the Upper Chehalis tribes. The Meshall, at the headwaters of the Chehalis River in the Cascades, spoke a version of the Upper Sahaptin language family. These people had horses and traded often with tribes east of the Cascades. The river people made their livings from the annual runs of salmon as well as from nuts, berries, and tubers gathered from the land. Four months of fishing was often enough to sustain families and tribes for a year and there was little need to hunt or trap animals for food. Tribe members also gathered berries and tubers from the forest and prairies.

Most villages were located at the mouths of rivers and creeks such as Lincoln Creek, Scatter Creek, Skookumchuck River, Black River, Cedar Creek, and at Grand Mound. The large settlement at Grand Mound was called aqaygt or "long prairie."

In February 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens convinced coastal tribes to sign the Quinault Treaty with the U.S. government, in which the tribes which exchanged title for much of southwest Washington for reservation lands. No members of the Chehalis tribe signed the treaty, but they have claimed rights under the treaty as affiliates. In 1864, the U.S. government set aside a 4,214-acre reservation for the Chehalis near Oakville in Chehalis (later Grays Harbor) County. The Indian population in 1855 was approximately 5,000. By 1875, it had dwindled to 1,200 from the effects of smallpox, measles, influenza, and venereal disease. By 1906, there were 149. In 2005, the Confederated Chehalis Tribes govern what is left of these tribal lands.

Settlement

The United States and Great Britain jointly occupied Oregon and the Pacific Northwest from 1818 to 1846. The Hudson's Bay Company established trading posts at Fort Nisqually on Puget Sound and at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. In about 1827, French Canadian Simon Plamondon staked a claim to 640 acres on the Cowlitz River and married the daughter of a Cowlitz chief. In 1838, the Hudson's Bay Company established the Puget Sound Agricultural Company and hired Plamondon to operate the 4,000-acre Cowlitz Farms. Cowlitz Farms represented the first non-Indian settlement in the future Lewis County.

Company employees raised crops and livestock to support the trading posts. Cowlitz Landing was the jump-off point between canoe travel north from Fort Vancouver and a path called the Cowlitz Trail through the forest and across prairies to Fort Nisqually. This path was originally a native portage between the Chehalis and Cowlitz rivers. Members of the U.S. Exploring Expedition, under Lt. John Wilkes, in 1841 used this route several times between Puget Sound and the Columbia.

Butcher John R. Jackson is credited with establishing the first claim in North Oregon on Jackson Prairie in 1845. In 1848, the United States formally established Oregon Territory and authorized a legislature, but residents of the Willamette Valley had been governing provisionally since 1842. They called the district north of the Columbia and from the Pacific Ocean to 122 degrees West longitude (about the crest of the Rocky Mountains) Vancouver District. On December 21, 1845, the Provisional Legislature of Oregon delineated Lewis County to honor Meriwether Lewis of the Corps of Discovery. Lewis County stretched from the Columbia to 54 degrees 40 minutes North (in present-day British Columbia) and from the Pacific to the crest of the Cascades. The only official function of the district was for taxation and legal proceedings. The county seat was wherever the justices of the peace decided to hold court. The first documented meeting of the county commissioners took place on October 4, 1847, in John Jackson’s cabin. The first criminal trial took place at Nisqually Landing in 1849. The commissioners also met at Simon Plamondon’s cabin at Cowlitz Landing, at Sydney Ford’s (county clerk) near Grand Mount Prairie, and at John Jackson’s (sheriff) place.

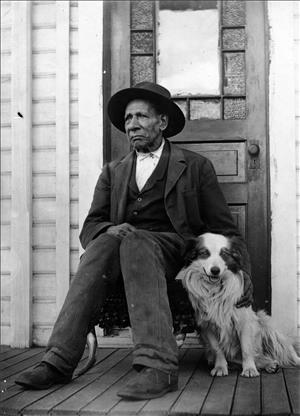

In 1850, African American George Washington (1817-1905) left Missouri for Oregon to avoid the racial discrimination against him. He was joined by his adoptive parents James and Anna Cochrane. Washington occupied a claim where the Skookumchuck River joined the Chehalis. But the Oregon Territorial Legislature had enacted a law prohibiting African Americans from owning land. The Cochranes filed a Donation Land Claim in their names and Washington continued to occupy the land. When the claim proved up five years later the newly formed Washington Territory did not prohibit Washington from owning land. The Cochranes sold the property to Washington for $3,400. Washington and James Cochrane were partners in a ferry over the Chehalis River and in an inn.

Virginian Billy Packwood settled in Nisqually in Thurston County in 1847 and in the 1850s managed to raise $6,000 in subscriptions to build a road through the Cascades at Naches Pass. Packwood is credited with exploring the eastern portion of Lewis County and for locating Cowlitz (or Packwood) Pass. A number of local landmarks bear his name.

In 1853, Congress split off the land north of the Columbia to be Washington Territory, and Lewis County, smaller than the Oregon version, was established between Cowlitz and Thurston counties. The first census enumerated 616 residents (Indians not counted) of whom 239 were males who could vote. The county took its final form of 26 miles by 96 miles in 1854 as the legislature authorized other counties in Southwestern Washington.

In 1851 New York native Stuart Schuyler Saunders settled at what would become Saundersville and then Chehalis. E. D. Warbass called his claim at Cowlitz Landing Warbassport, which would later become Toledo. During the Indian War of 1855-1856, settlers constructed blockhouses at Grand Mound Prairie and on the Chehalis, but there were no violent confrontations in Lewis County.

In the 1850s and 1860s, Cowlitz Landing was the hub of activity in the area. There was a store, a hotel, the Cowlitz Post Office, and several other buildings. Travelers left the river there to start an arduous journey overland through the forest, across several prairies, and over two rivers to reach Puget Sound. In 1864, the 95-foot steamer Rescue provided irregular service up the unpredictable Cowlitz from Portland. After three years, the business failed. Despite heavy reliance upon river transport by local farmers, a succeeding business using the Rainier also failed.

Here Comes the Train

The Northern Pacific Railroad (NP) reached the Chehalis River in 1872 from Kalama on the Columbia and the line reached Tacoma the following year. Regular service between the river and Tacoma began in January 1874. Just four months later, as many as 30 people per day were getting off at stations between the Columbia and the Sound. Residents of Saundersville built a warehouse to induce the NP to build its line through there. NP engineers dropped Newaukum from their design and took advantage of the free warehouse.

Claquato had been the county seat until the railroad bypassed the small town and on August 1, 1874, the county commissioners moved the county seat to Saundersville. Saundersville became Chehalis in 1879.

In January 1875, George Washington filed a plat on a town he called Centerville and over the next 15 years, he sold 2,000 lots. This was incorporated as Centralia in 1886 (there was already a Centerville in Eastern Washington).

The railroad and the dredging of the Chehalis in the 1880s made possible the exploitation of the county’s major resource -- timber. Workers and equipment could be brought in and logs and finished lumber could be shipped downriver to Grays Harbor and by rail to the east. The introduction in the 1880s of the geared locomotive for steep grades and the donkey engine to move logs meant that previously inaccessible stands of immense trees fell to the crosscut saw. Steam-powered mills featured circular saws, gang edgers, and afpower log turners and drivers. Lumbering became big business and the principal industry of the region attracting immigrants to new communities.

In the 1880s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cleared snags from the Chehalis River. Steamers could reach Montesano from Grays Harbor and, during high water, to the rail connection at Chehalis. On the Cowlitz, steamers boarded passengers at Toledo for the 24-hour trip to Portland. Other passengers along the way could flag down a ride, but the railroad was the principal means of transport.

The Twentieth Century

The turn of the twentieth century saw slow, but steady growth in the county. The new communities focused on building schools, churches, granges, and fraternal organizations such as the Masons, the Knights of Pythias all expressed the growing sense of community in the small towns. The Southwest Washington Fair held its first celebration in October 1891. The U.S. government set aside vast tracts of forest as a national forest in 1897 (later the Gifford Pinchot National Forest). While preserving these lands from settlement, loggers were permitted to pay the United States for the trees they cut.

After 1900, county officials focused on building roads within the county and in connecting to the eastern side of the Cascades. Some even dreamed of dredging the Chehalis River to allow seagoing ships to dock at Chehalis. Unlike the roads, this idea never worked out.

The logging and milling operations attracted thousands of wage-earning workers. These in turn attracted labor organizers who fought low pay and unsafe working conditions. As elsewhere in the nation, the struggle led to violence and the so-called Centralia Massacre of November 11, 1919, thrust the city into national infamy. Members of the aggressive Industrial Workers of the World were confronted by (or confronted, depending on the account) veterans of World War I who were parading on Armistice Day. The gun battle left four dead. Angry citizens lynched IWW organizer Wesley Everest (who was also a veteran). Several IWW members were prosecuted and imprisoned, but no one was ever charged in Everest’s death. The statue of a soldier of the World War in Washington Park commemorates not war dead, but the slain veterans of 1919.

The timber industry, a mainstay of the local economy, went through a slump in the 1920s followed by the Great Depression in the 1930s. World War II brought an increased demand for wood and agricultural products and a return to prosperity. Lewis County citizens subscribed to their own P-40 fighter plane named Chehalis Tomahawk.

After the War

The post-war years saw growing change to the county beginning with the completion of the White Pass Highway over the Cascades on August 13, 1951, and the four-lane Pacific Highway linking Portland to Seattle. This would later become Interstate 5 and travelers crossed the county in minutes rather than days. The City of Tacoma announced plans for two large hydroelectric dams on the Cowlitz River in the late 1940s, but opposition by outdoor groups stalled the projects into the 1960s. The projects brought hundreds of millions of dollars of construction work to the area. The Lewis County Public Utilities District completed its own 140-foot-high dam and 70-megawatt generating station in 1994 at Cowlitz Falls before environmental legislation put an end to hydroelectric development.

When the Department of the Interior published its discovery of 1.75 billion tons of bituminous coal under the county in December 1951, City of Centralia officials began discussing construction of a coal-fired power plant. But it would take 20 years for that idea to take form. The $200 million Centralia Steam Electric Plant opened in 1971, constructed by a number of public and private electrical utilities in the Northwest. Two coal-fired boilers each produced 700,000 kilowatts of electricity.

In May 1980, Mount St. Helens erupted just across the county line in Skamania County, but Lewis both felt and enjoyed the aftermath. Volcanic ash stranded 200 residents in the eastern portion of the county after the first eruption on May 18 and a subsequent eruption dropped ash over the western part. The calamity took 57 lives, but spawned a tourist attraction. No fewer than three visitors’ centers opened in the county along with other tourism-related businesses.

In 2000, Lewis County boasted approximately 69,000 residents and its largest employers are the Providence Centralia Hospital (760), the TransAlta coal-fired steam plant (680), Lewis County government (650), and Wal-Mart (560). The county's jobs are significantly more blue collar than the rest of Washington state at nearly 37 percent.