Cal Anderson Park, a beautifully renovated and expanded park on Seattle's Capitol Hill, re-opened on September 24, 2005. Originally one of Seattle's Olmsted-designed parks (named "Lincoln Park,"), it had by 1993 deteriorated into weeds, trash, and a graffiti-covered rest room, and was avoided by community members as a druggy and dangerous place. Kay Rood and the community organization Groundswell Off Broadway was a prime mover in the process of organizing to rebuild the park into a beautiful community asset with an undergrounded reservoir, a playground, community buildings, a water feature, paths, gardens, and benches. This is Kay Rood's story of the long process of rebuilding the park, which is named for Cal Anderson, Washington's first openly gay legislator.

Blue Sky on Capitol Hill

“Community parks have the power to reveal that neighborhoods are integral parts of the city. People live here. They work and pay taxes. They’ve invested in the city’s future. A park is not scenic welfare. It is equity.”— Herbert Muschamp, architecture critic, The New York Times

The final step in the transformation of historic Lincoln Park to Cal Anderson Park took place at a festive re-opening celebration on September 24, 2005. The long-awaited rejuvenation brought renewal not only to our neighborhood park, but to the entire community. For the many thousands of Capitol Hill residents, that day marked a wonderful fresh beginning for a new generation of park use and enjoyment. For me, it was the culmination of 12 years of volunteer advocacy and involvement. The restored site has at last been brought to its highest and best use as a community gathering place of safety, beauty, and accessibility.

It wasn’t always a sure bet, though. It could have gone a lot of different ways.

My initiation into park activism began in 1993, when I saw that the thistles in the park across the street were three feet higher than the few pitiful, parched little tea roses that languished there in a corner plot. The park looked like a prison yard from an old black and white movie, with rusted double fencing, a cinder sports field, a small rundown playground, an ugly and dangerous brick restroom building often covered with graffiti, and a semi-permanent population of transients and druggies dotting the landscape. Eleven acres in the middle of south Capitol Hill, and people were crossing the street to avoid walking even on the sidewalk next to it!

The four-acre open reservoir with its fountain jet occupied the northern half of the park, but its soothing presence was surrounded by chain link fencing with barbed wire along the top. The place didn’t even have a name. Something was very wrong here. So I began a correspondence with the Parks Department full of photo documentation and righteous indignation over the failure of the city to improve and maintain this public site for the deserving and open-space-deprived citizens of Capitol Hill.

As time went by, as I met with various Parks Department personnel, it dawned on me that perhaps the responsibility for the place was a shared one. If I wanted a better park, I could do something about it.

I had been the sole proprietor of my own custom picture-framing shop since 1979, as well as a professional printmaker, and had long been accustomed to working alone. Working with organizations and bureaucrats and going to meetings were foreign experiences for me. But I knew that bringing a park back to life is not something you can do on your own.

With my new awareness that this park belonged to its citizens, I spoke with neighbors and learned that we were all concerned about the unsafe and unused park in our midst, but were waiting for Someone to Do Something About It. Everyone was enthused at the thought of its transformation into a true civic space with a playground, gardens, benches, and where people of all ages could safely stroll, relax, and play. We formed a steering committee and started meeting informally in one another’s living rooms. I proposed the name Groundswell, since it seemed we truly were. (The “Off Broadway” was added to distinguish us from Groundswell Northwest, a successful community group in Ballard, whose existence we had not been aware of. I called Lillian Riley to ask if they minded our having a similar name, and she said “Be my guest! I’d love it if there were Groundswells all over Seattle -- Groundswell Southeast, Groundswell West, Groundswell Downtown -- whatever.”)

Around that time (1993), the Water Department was considering building a large concrete block chlorination building in the park to house new water chlorination equipment, a change from the existing gas chlorination process, to disinfect the drinking water at the park’s Lincoln Reservoir. As proposed, the building seemed the final disfiguring indignity to the park -- insult to injury. There were several community meetings to discuss it, and neighbors were eloquent about what they didn’t want. Gradually the discussions turned to what we might want, if only we could.

This was the first time I had heard the term “blue sky” session. Now, making wish lists is not the way I go about decision-making in my life, so at the time this seemed indulgent and really very unproductive to me. We wanted a safe, accessible, attractive park and allowed ourselves to imagine and describe it. I could not have known then that “blue sky” is literally what we would get at Cal Anderson Park -- an unobstructed expanse of sky that was only revealed with the new park design. But that was still 12 years in the future.

As it happened, the chlorination building was set aside as the Water Department began to consider new ideas about reservoir covering. But the “blue sky” idea had taken hold of my imagination.

I got some volunteers together and we built a stunning new perennial border at the park’s northeast corner, at E Denny Way and 11th Avenue, where the thistles had been. Paul Repetowski donated the design and the plants came from nursery and neighbor donations. We put a sign there that read “Brought to you by your neighbors and Groundswell Off Broadway.” This was the first visible park enhancement here in about 40 years as near as anybody could remember, and it brought a lot of smiles and encouraging remarks from passersby. We built a second larger garden two years later at the northwest corner.

Not long after we began organizing, we learned, to our surprise and delight, that our park and reservoir site had been designed in 1904 by the Olmsted Brothers, Landscape Architects of Brookline, Massachusetts. Well! The premier American landscape architects -- who, with Calvert Vaux, created Central Park in New York City, and so many other important American public spaces. I read up on Olmsted and learned about the system of parks and boulevards that they designed and Seattle built.

This information gave us a new idea of our park as an historic place, connecting our neighborhood to not only city, but national, history. A sense of responsibility as stewards of our park was introduced into our thinking. Meeting Jerry Arbes and Anne Knight from the Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks (FSOP) began a very productive community partnership as well as a friendship that has continued to this day. These two were essential to all that was to come for their experience in park issues, their problem-solving abilities, attention to detail, insistence on quality, and most of all, for their dedication to this place.

One of the oddities of our park was that although the playfield and the reservoir had a name (Bobby Morris Playfield; Lincoln Reservoir), the park as whole did not. In 1922, the original name, Lincoln Park, was appropriated by the West Seattle park that still bears that name. We were technically and somewhat archaically “Historic Lincoln Park,” but it was obvious that if we were to have a new park, it would need a new name.

State Senator Cal Anderson died of AIDS in August 1995, just as Groundswell was mobilizing on our first big grant project. One of our steering committee members suggested that we name the new park for him, and the idea seemed just right from the very beginning. I never knew Cal, but I know from all I have read and heard that he was an exceptional person. Widely praised for his work ethic and personal integrity, he worked tirelessly on behalf of the disenfranchised. A park in the heart of the 43rd District named for him would bring a pride of place to our community, a new name for a new future. We tucked the idea away. I figured we would know when the time was right to propose it, which was not until we had assurances that there would be a park worthy of Cal’s name.

Our first big public meeting at the First Christian Church was exhilarating. We did it the old-fashioned grassroots way, by posting notices locally and going from door-to-door with flyers that asked What Do You Want For Your Park? We had a great turnout of about a hundred interested neighbors, and there were some city employees present, too. The atmosphere was electric and we had the sense we were tapping into the community’s concern and energy. After a general spirited discussion about park conditions, we broke into small groups by topic to solicit and document ideas for improvements and ask for volunteers to join us in carrying them out.

After a few more months, we had a mailing list of about 500 people. The ground was definitely swelling! There was a lot of interest and neighbors were excited and supportive that they would have a voice in how the park would be improved and developed. We began to think of rejuvenating the park as our job.

The Parks Department had already begun a playfield resurfacing project when we learned that a state grant they had received had specified making “park-wide” improvements. Somehow, prices had escalated and all the money, more than $800,000, was going to be spent for a new playfield surface with very little community notice or discussion. Groundswell, with its newfound solidarity of purpose, asked for meetings to discuss the playfield project in the context of the whole park and made proposals of our own. We recognized that the existing cinder surface was problematic, but wondered why it had to be replaced with a new and untried synthetic/grass system at the expense of the other eight acres of the park. We were able to review the budget and find ways to economize, which left an approximate $75,000 surplus. We proposed creating some welcoming entrances along the park’s south border on East Pine Street, and worked with The Berger Partnership landscape architects, who were already working on the playfield project, to design them. These entrances were to set the tone for the rest of the park -- low granite walls with historic ornamental metal light fixtures, crowned by round globes. We used city surplus gray granite tiles for the entry arrival areas, created distinctive scoring patterns in the sidewalk, and redid the ramp at the southwest for improved ADA accessibility.

The Parks Department had recently hired a new community liaison, Beth Purcell, who was effective in negotiating ideas and issues between our energetic new group and what seemed often rigid Parks Department planning methods and processes. I learned that when you find yourself dealing with an unhelpful public servant, you can keep looking until you find a helpful one. Sometimes, however, the buck stops and you just have to deal.

At different times over the life of the park project, we received both considerable support and considerable resistance from the City. One of the most important things I learned is that if there is the will to address the problem positively, there is always a positive solution. Sometimes it seemed that the public wasn’t expected to have a good idea, and it wouldn’t be considered if that’s where it came from. At various points we were told that some of our ideas were simply not possible, or that there was no money for them, or there was no precedent for them, or they were too ambitious. Most of these obstacles were overcome, with time, by pointing out mutual benefits, by demonstrating our willingness to be flexible, by trying another more creative approach, and by being persistent. Especially by being persistent. We always strove to get the City to realize that our goals and their goals were essentially the same -- a safe, accessible, and attractive park, with quality design and lasting materials, which honored our history, and our neighborhood. We didn’t win all our battles, but I think we prevailed on the ones that really mattered.

We wanted to determine what further improvements the community might want for the park. The city’s Department of Neighborhoods (DON) had a matching fund program whereby volunteer labor, and donated materials, professional services and in-kind contributions were assigned a value and then matched for that dollar amount. Cash, of course, always counts. This meant that our steering committee needed to find all the different ways neighbors and supporters were willing to contribute, and a group of community organizers were born.

We applied for and received a $5,000 matching fund planning grant. With these funds we held a series of community park plan/design meetings with the Parks Department, attended by more than 200 people, to create our first Conceptual Park Master Plan. It focused on the middle lawn area, with its restroom and playground, and the land peripheral to the reservoir. The community’s priority list created at this time provided us with our To Do list for the years to come. Replacing the unsafe and unsightly restroom building was first on the list.

The next step was making those improvements, and after overcoming DON’s Byzantine grant forms, we got a $68,000 matching fund construction grant in 1996. The improvements we chose were basic: removing old fencing, creating new plantings along East Pine Street between our handsome new entrances, 10 new World's Fair benches appropriate to an Olmsted park, 25 new trash containers to replace the beat-up metal cans (some of which had been chained to trees) currently in use. Almost 500 feet of tennis court fencing was replaced, and we got a crash course in lead poisoning in old paint and the delays such discoveries can cause. We learned project management on the job with firsthand experience dealing with contractors’ schedules, delays, and disputes.

Neighborhood Planning was Mayor Norm Rice’s new program to involve citizens in their own community’s planning efforts, and it was during this time (1996) that the 37 Neighborhood Planning Committees were just beginning to do their work. There was considerable pressure for Groundswell to be incorporated into that process. It seemed to me an unnecessary delay with an uncertain outcome. Since Capitol Hill Neighborhood Planning was just that -- planning, we felt we had planned enough and were ready to move on to pursuing funding and construction. We did not want to wait. It was the right thing to do -- as events unfolded, Groundswell and the committee worked well and cooperatively in a parallel way with periodic reciprocal updates, and creating Cal Anderson Park (for we were already calling it that informally) emerged as Capitol Hill’s highest-voted priority at its final community validation event in 1999.

Proposals to cover the Lincoln Reservoir had been made intermittently since the early 1970s for a variety of reasons, but none had been realized. In the early 1990s, however, the State mandated that all Seattle’s open reservoirs be covered to protect water quality. The Water Department, now called Seattle Public Utilities (SPU), evaluated the entire reservoir system to determine which would be covered first, and by what method. Lincoln Reservoir was almost 100 years old, it was a notorious and documented leaker, and it was at risk for airborne and other contaminants because of its close proximity to the neighborhood. There was talk of some reservoirs getting plastic or wood covers, but by now we were very clear that we not only wanted Lincoln to be the first reservoir to be covered under this program, we wanted buried water tanks with turf over the top for park land.

The first list that came out had us at Number 3. Because Groundswell was organized and already working on the park, we had a voice in that process, and we lobbied hard for our choice. We were elated when Lincoln was chosen not only to be the first, but also to be a buried reservoir. We were to be the recipients of new land -- what Mark Twain famously said they don’t make anymore. Planning by both the city and the community began for this massive project.

Working with Groundswell was a new kind of experience for Seattle Public Utilities. In the past, they had little need for, or experience with, collaboration with community groups on its capital projects. The enormous impact and physical ramifications of such a large and complicated construction project in the midst of our legendarily densely populated neighborhood required coordination and cooperation. The learning curve was a long one. It didn’t help that the Parks Department and SPU had historic rifts and didn’t always see eye to eye. We did our best to work with both departments to make a successful project we could all be proud of. We negotiated and signed a Memorandum of Agreement with SPU to clarify the community’s and the utility’s needs on this complex project.

We were aided by the creation of an Interdepartmental Team, or IDT, which was convened by the Mayor’s Office (the mayor was then Paul Schell). This group met monthly for seven years. Although not always harmonious, it was always a benefit to all of us as a clearinghouse for news and shared information relating to the many aspects of the park/reservoir project. A series of construction delays brought about by budget cycle considerations held up the project. In 2002, Groundswell participated in a “value engineering” process in which SPU sought more efficient and economical methods on the reservoir project. The project was back on track.

The community had long treasured the water view provided by the reservoir and the sound of the fountain, and so from the very beginning we sought to replace those elements on the top of the lid in the form of a water feature. This is one of the things we were told was simply not possible.

Connecting to other organizations on the Hill seemed a natural and useful evolution, and I represented Groundswell for four years on the Capitol Hill Stewardship Council, where Groundswell had an organizational seat. I also participated in the Capitol Hill Transportation Committee, a coalition of neighborhood groups that attempted to deal with the ramifications of Sound Transit’s future construction impacts and schedules.

The Capitol Hill Safety Coalition was another group I participated in, which in its brief but intense 20 months of life, was able to effectively raise the issues of Capitol Hill’s considerable public safety problems to the attention of the Mayor and City Council. Drug and alcohol activity and the other illegal behaviors that accompany them continued to escalate to an alarming degree in the park and surrounding neighborhood over this time.

We negotiated successfully to have community representative Rob Hard on the committee that selected KCM/TetraTech as the contractor for the reservoir replacement project. KCM, in turn, chose The Berger Partnership as the landscape architect subcontractor. Having Berger on the project brought much-appreciated and valuable continuity for us. Jeff Girvin, who understood completely the value of community ideas and energy, was especially great to work with.

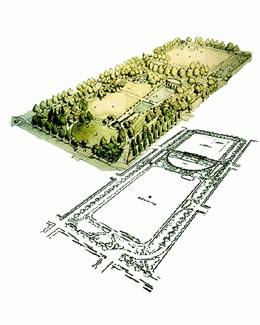

Then in 1997-1998, SPU sponsored a series of six intensive Master Plan Design Workshops with the community, facilitated by The Berger Partnership. The 1 Percent for Art program kicked in, and artist Doug Hollis was chosen to work on the design team with Berger. So the community re-engaged wholeheartedly in the Master Plan process for the second time, this time with four more acres of land to design with. The attendance and energy level was high at the five community plan/design meetings. Our collaboration produced a Park Site Master Plan, which took into account both the site’s historic legacy and contemporary needs and uses.

In November 1998, the Parks Department and SPU had co-sponsored the historic landmark nomination of the park/reservoir site, making a series of presentations to the Landmark Preservation Board and its committees, in which Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks and Groundswell Off Broadway participated to a significant degree. The historic material FSOP provided was central in securing the 1999 designation and enlarged all parties’ understanding of the site’s importance. We all became regular visitors down at the Arctic Building.

There was still no funding for the park. A King County levy, which would have provided some money, had failed a few years before. But the 2000 $1.98 million ProParks Levy was taking shape, and if it won the public vote, our park was in line for $5 million. Once again, the fact that Groundswell had already been working on the park and was in place to demonstrate the need for more park improvements made a big difference in the funding priority and attention to our project. We were suited up and ready! Both Jerry and I served on the ProParks Citizen Advisory Committee and we all worked on the campaign.

Around this time, the sleeping giant of Sound Transit (the regional transportation authority) reared its head. Previously, the preferred alternative for the future Capitol Hill light rail station had been under Broadway Avenue, a half block to the west of the park’s western border. Now the station site had shifted east, into the park. The new plans showed that a big portion (approximately 50 feet by 300 feet) of the northwest corner of the park would be taken for the above ground construction zone for the underground station, for an undetermined number of years. However, Sound Transit had some organizational and fiscal problems and suddenly this part of their project seemed to be on hold. But for how long? Would the City blink? Would the park remain just a plan? Would Sound Transit really dig up a newly built park? No one knew. If Sound Transit’s plans were momentarily uncertain, ours weren’t. We moved ahead.

In 1997, I had written and assembled a Cal Anderson Park Prospectus for State Representative Ed Murray, at his request. This document, with its several inches of addenda, provided the background of the park project, the documented need and desire of the neighborhood, examples of the work Groundswell had done to date, along with our assertion that this was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to build a truly world-class urban park on land where none had existed before. Three years went by before the exciting news came that Ed had facilitated a donation of $250,000 in State funds for the cause. Seattle Central Community College, our near neighbor to the west and early supporter of the park project, agreed to act as fiscal agent.

We decided the best use of the money would be to get it matched by another Department of Neighborhoods matching fund grant. So, with park master-plan funding still not forthcoming, Groundswell went ahead and wrote a third grant application to the DON, this time to build a multi-use Shelterhouse complex. We chose to build in the park’s center, to avoid conflicting with the imminent reservoir replacement, so even if the rest of the park didn’t get built, at least we would have this new building complex. The proposal included a restroom building (we were finally able to address this community priority), a Parks maintenance building, and for the first time in our park, a community activity building. Called the Olive Corridor Project after the vacated east-west walkway that crossed the park, it was successful and we were awarded $250,000, which I believe is the largest such construction grant ever awarded by the DON. The Shelterhouse complex was to become the first constructed element of our Park Master Plan.

We interviewed architects and chose local architect Tom Roth. Working with him and Parks Project Manager Don Bullard occupied us for several years, overseeing the many details involved in building three buildings. Jerry and Anne were old hands at building development and working with architects, but I was a novice, once again learning on the job.

We broke ground in 2001 with the demolition of the old restroom. That restroom was the symbol of everything that was wrong with the old park – unsafe, unsightly, inaccessible. I never knew slinging a sledge hammer could be so satisfying.

My new skill set now included organizing, lobbying, public speaking, grant writing, fundraising, negotiating, newsletter writing, editing and publishing, and demolition. I had quit asking myself how I’d gotten so deep into this work. It was just too good an idea to quit now. The important thing was to see it through. The stakes were high and the need was so great -- and people’s expectations had been raised. It was my job.

In November 2000, the ProParks Levy passed. Suddenly (finally!) the park’s future began to seem a lot more real. We had a design, we were getting land from the reservoir replacement project, and now we actually had funding. We circulated petitions and solicited letters to advance the name Cal Anderson Park, and the Parks Board and Parks Superintendent Ken Bounds accepted it. We dedicated the new Shelterhouse and gave the park its new name in a dedication ceremony on April 13, 2003, just as SPU at last began construction on the reservoir replacement project. So while some construction fencing came down, much more went up.

Another dedication that same day was that of the Sophora japonica, or Chinese Scholar Tree, which I had nominated for designation as a Seattle Heritage Tree. I had always loved the sculptural form of this tree in the park’s northwest corner, which we think was planted at the time of the Olmsted plan. Having it recognized as a neighborhood landmark brought one more distinction to our park.

In the fall of 2004, Sound Transit once more revised its preferred alternative boundaries by shifting the Capitol Hill station site again, this time to the west, just enough so that the park would not be directly implicated in the construction zone. Since the park was already about 90 percent complete, this was a great relief.

More than once, the simple fact that Groundswell existed, that there was an active community group focused on the park, gave us standing and a voice in how decisions were made in it and around it. For example, we were able to negotiate several hundred feet of new sidewalk at the north and the south ends of the park (concrete work is incredibly expensive) at no cost to the project by working with existing projects adjacent to the park.

In 1998, City Light was doing some vault work in E Pine Street and strayed (without community notification) into the sidewalk paving we had just installed with our matching grant project 18 months before. We arranged an emergency meeting with the utility and City Council members to address the problem, and were able to get the City to replace the sidewalk with an historic cobblestone edging all along the park’s southern border, a new, improved bus stop area, three new curb bulbs, and a specially scored crosswalk across Nagle Place.

Then again in 2000, when a local fiber optics company announced they would be laying cable under the north side of the E Denny Way sidewalk, we were able to intervene and persuade them to place it under the south side, and thereby get the benefit of a new sidewalk along the park’s northern border.

The reservoir replacement and water feature were completed in March 2005. The Parks Department still had some final touches to do on the play area, as well as some landscaping, garden rejuvenation, and entry improvements, and most importantly, getting the grass established. Delays were required to accomplish this, and it began to look like the park would not open on the Fourth of July as we had hoped. By late June I learned we would have to wait until fall for the reopening.

I was in a retrospective mood as the park neared completion. Looking back, I mostly felt lucky to be part of an effort that resulted in creating a place with such a lasting legacy. That there was a need for this park was never in doubt, but how we addressed it and how we got there was quite an educational ride. We prevailed in spite of obstacles, delays and misunderstandings. We did have some luck, but we also made a lot of our own luck. I did some writing about the project, and some tallying: The total value of grants obtained, and direct and leveraged contributions to Cal Anderson Park by Groundswell Off Broadway over the last 10 years is valued at $1.12 million.

Major parts of the park had been off-limits with construction fencing for almost five years by now. With the park topography’s having been raised to accommodate the buried water tanks, only glimpses of the new park were possible from the sidewalks -- the historic lighting fixtures had been in place and functioning since the previous fall; you could see the graceful curves of some of the paths, some of the large cone/water source, and part of the recreated parapet walls describing the historic reservoir’s perimeter; you could see some of the many new trees and their stakes, and parts of the tops of the new play area equipment. The new basketball court near Nagle Place had already been in daily use for a couple of months. Certainly the entrances were visible, but their steps were still blocked with construction fencing. The suspense was intense!

Meanwhile, the Parks Department had begun another resurfacing project for the Bobby Morris Playfield, this time with a synthetic all-weather turf, which would allow more soccer and baseball games, and bring more activity in the park. With this project, the transformation of the entire 11 acres was complete: Almost every square inch had now been upgraded, restored, or recreated.

By late summer, the grass had taken hold and was strong enough to withstand the heavy use it would be getting. Planning the grand re-opening celebration was definitely one of the fun parts of the job. The playfield surface was completed just days before the event.

Thousands of people came to celebrate. We hired the Rainbow City Band, a clown, a juggler, and a stiltwalker in a peacock costume. There were lots of speeches, and Cal’s mother, Alice Coleman, got the big scissors to make the first cut of the ribbon. There was cake and coffee, lots of photographs were taken, and people just could not stop smiling. It was a perfect sunny-yet-cool day in late September, with puffy white clouds scudding across the biggest, bluest expanse of sky -- that blue sky we had dreamed of 12 years before.

As I write this on the last day of 2005, I have to say that the park is everything I had hoped for and more. The biggest surprise is the breathtaking sense of space from within the park, which makes it seem much larger than it really is. The park is already universally loved and used. The joggers, bicyclists, chess players, double-dutch jump ropers, extreme frisbee-ites -- they’ve all been here. The new play area is seldom empty -- those kids waited a long time to get back on the swings. I have seen a man practicing bagpipe dirges, a child floating a toy boat in the reflecting pool, and a Tai Chi class moving silently in the damp early morning grass. The biggest gratification is that the variety of uses is as wide as the variety of people, and with that, a new balance of enjoyment and respect for one another, and for this place, has been achieved.

People come with their children, their parents, their students, their teachers, their visitors, and boyfriends or girlfriends, and many just come on their own to sit and read a book on a bench. The sound of a rushing mountain stream from the water feature’s source provides the aural backdrop to all this human activity. It is a compelling focal point as well. My favorite description of it is one I heard a young father improvise on the spot to tell his boys: “I think it’s the story of how water races down the mountain, gets channeled into streams and rivers, and then eventually flows quietly out to sea -- and then the cycle starts over again.”

The park has become both a kind of crossroads that people pass through, and a destination where they pause for a while. Even in the cold, wet winter weather, I see people bundled up and marching purposefully into the park taking their daily constitutionals. That Frederick Law Olmsted was really on to something, and I hope it will endure here, for another hundred years.