On June 4 and 5, 1942, more than 1,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, including many American citizens, are forced to leave the Yakima Valley in response to Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February. The Executive Order calls for the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific Coast. The evacuees are compelled to board specially chartered trains that take them to an assembly center at the Portland Livestock Exposition grounds in Portland, Oregon. From there they will be shipped to an internment camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming, where most will be detained for the remainder of World War II.

The first recorded settlers of Japanese origin to the Yakima Valley were the Kimitaro Ishikawa family, which arrived in 1891. Subsequent immigrants of Japanese origin worked as hired labor clearing land for an orchard on the Yakama Indian Reservation, and working for plant nurseries and as farm laborers. Eventually many of them leased land and entered the farming business for themselves.

Most plots farmed by Japanese immigrants comprised fewer than 40-acres, although some larger Japanese-owned businesses produced larger-scale crops of alfalfa, onions, and potatoes. By the early twentieth century, Japanese-owned rooming houses, grocery stores, commercial laundries, and other small businesses dotted the Yakima Valley, many around the Wapato area.

Japanese immigrants were denied the right to apply for United States citizenship under the March 26, 1790, Naturalization Act. In 1921 Washington State enacted the Alien Land Act, which prevented non-citizens and those ineligible for citizenship from owning or leasing land. For this reason many Japanese parents (Issei) including those in the Yakima Valley, purchased land in the names of their American-born children (Nisei).

Immediately following the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, six leaders in the Yakima Valley Japanese community were arrested and held in the Yakima County Jail. On December 9, 1941, Wapato Mayor George H. Hodgson spoke out in defense of Yakima Valley Japanese Americans' loyalty to the United States, saying "They make their livelihood here, have reared their families as Americans and feel that this country's flag is theirs rather than the flag of the rising sun" (Heuterman, p. 114). The flag of the Empire of Japan featured the image of the rising sun.

Reverend Tessho Matsumoto, leader of the Wapato Buddhist Church, also spoke in defense of his community's loyalty to the United States and removed the swastika image that had formerly adorned the church facade. Prior to its appropriation by Adolph Hitler (1889-1945), the swastika was used by a wide variety of groups worldwide, including Buddhists, as a protective symbol.

Issei bank accounts in the Yakima Valley were frozen. Accounts belonging to Nisei were not frozen, but proof of American citizenship was required in order to make withdrawals. On December 15, 1941, the Federal Reserve Bank unfroze the bank accounts of any Issei who had lived in the United States continually since June 14, 1940. Japanese Americans offered their services to help with war effort home-front tasks. Nisei schoolchildren were permitted to continue attending their classes, and many non-Japanese Yakima Valley residents rallied around their Japanese American neighbors.

On January 14, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Presidential Proclamation Number 2537 requiring that enemy aliens (which included the Issei) to register. On January 23, 1942, the Wapato Japanese Language School burned down under suspicious circumstances.

On February 28 and March 2, 1942, a select committee chaired by congressman John H. Tolan met in Seattle to investigate the feasibility of evacuating Issei and Nisei from coastal Washington to the Yakima Valley so that they could help grow crops for the ever-increasing war effort. These farm workers were to labor under armed guard. Ultimately the committee bowed to concerns that much of the agricultural work in the Yakima Valley was seasonal and thus not sufficient to warrant importing the Japanese American evacuees. Washington Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966) also voiced concern about protecting dams and irrigation canals in the Yakima Valley from what he perceived as potential sabotage, while admitting that evacuating the Japanese families currently farming some 9,000 acres in the Yakima Valley would reduce crop production.

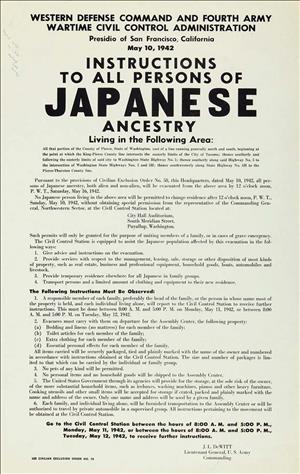

But even as the Tolan committee was hearing testimony, however, Lieutenant General John DeWitt (1880-1962), head of the Western Defense Command, issued Public Proclamation Number 1 delineating the western half of Washington, Oregon, and California and the southern third of Arizona as military areas from which Issei and Nisei must be removed. The Yakima Valley fell within this area.

On May 26, 1942 Lieutenant General DeWitt announced that Issei and Nisei in six central Washington counties including Yakima County would be evacuated by June 7. On May 25, 1942, a 50-member Army field artillery unit arrived in Wapato to process evacuees. A number of Nisei assisted in this task, processing themselves and their families for imminent evacuation. On the evenings of June 4 and 5, 1942, these Japanese Americans, their belongings limited to what they could carry, boarded trains for Portland and then in early August on to Heart Mountain Relocation Center 12 miles northwest of Cody, Wyoming, about 800 miles from home.