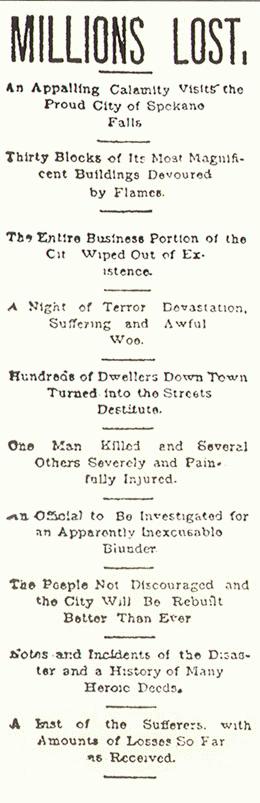

On Sunday, August 4, 1889, fire destroys most of downtown Spokane Falls. It begins in an area of flimsy wooden structures and quickly engulfs the substantial stone and brick buildings of the business district. Property losses are huge, and one death is reported. In initial newspaper reports the fire is blamed on Rolla A. Jones, who was in charge of the water system and was said to have gone fishing after leaving the system in the charge of a complete incompetent. Within weeks, city fathers will exonerate Jones, but the initial account, although false, will be repeated in many histories of the fire. Spokane will quickly rebuild as fine new buildings of a revitalized downtown rise from the ashes.

The fire began shortly after 6:00 in the evening. The most credible story of its origin is that it started at Wolfe’s lunchroom and lodgings opposite the Northern Pacific Depot on Railroad Avenue.

The flames raced through the flimsy buildings near the tracks. The nearby Pacific Hotel, a fine new structure of brick and granite, was soon engulfed in the wall of fire advancing on the business center. Church and fire-station bells alerted the public and the volunteer fire department, which had formed in 1884. Firefighters, attempting to put out the flames, could not get sufficient water pressure in the hoses to do so.

Spokane was no frontier town composed entirely of makeshift wooden structures, but the fire did start in such an area, where rubbish between buildings provided ideal tinder. The fire consumed that part of the city and then moved on.

Firefighters began dynamiting buildings in an attempt to deprive the fire of fuel, but the flames jumped the spaces opened and soon created their own firestorm. In a few hours after it began, the Great Spokane Fire, as it came to be called, had destroyed 32 square blocks, virtually the entire downtown.

There was one fatality, George I. Davis, who died at Sacred Heart Hospital of burns and injuries when he fled (or jumped) from his lodgings at the Arlington Hotel. Many others were treated at the hospital, where the nuns served meals to the newly homeless boardinghouse dwellers, mostly working men, plus others referred to in newspapers as the “sporting element.” Estimates of property losses ranged from $5 to $10 million, an enormous sum for the time, with one-half to two-thirds of it insured.

Some of Spokane’s leading citizens immediately formed a relief committee, and other cities donated food, supplies, and money. Even Seattle, just recovering from its own disastrous fire of June 6, sent $15,000. The National Guard was brought in to assure public order, to guard bank vaults and business safes standing amid the ruins, and to prevent looting. Mayor Fred Furth issued dire warnings against price gauging. Unemployed men immediately found work clearing the debris, and any who declined the opportunity were invited to leave town.

Businesses resumed in a hastily erected tent city. They included insurance adjusters, railroad ticket offices, banks, restaurants, clothing stores, and even a tent in which the Spokane Daily Chronicle carried on publication.

Early newspaper accounts contained only one explanation for the weak water pressure and failure to check the flames: that Superintendent of Waterworks Rolla A. Jones was away fishing or working on his steamboat -- accounts vary -- instead of tending his post, and that he had left the pumping station in the care of an incompetent substitute. S. S. Bailey of the City Council claimed to have run “to the pumping station as soon as the alarm was sounded and found that Superintendent Jones had left a man in charge there, who, by his own admission, was totally incompetent to handle the machinery, not knowing how to increase the speed of the pumps” (Spokane Falls Review, August 6, 1889). Other papers as far away as The New York Times repeated this story almost verbatim.

To its credit, the City Council quickly appointed a Committee on Fire and Water to explore all possible reasons for the failure. Its report on August 14 exonerated Jones, but he resigned anyway. Refuting newspaper accounts, the City Council report stated: “It appears that the man left in charge of [the] pumping station during the absence of Supt. Jones is competent and reliable and of twenty years of practical experience in machinery and pumps ...”

The committee attributed the failure of water pressure to a burst hose rather than dereliction of duty and further reported that some members felt “bad management on the part of the fire department should be considered as the main cause of such an extensive conflagration” (Nolan, 50). Although this official interpretation of events was made known, Jones’s guilt was firmly lodged in the public mind and has been repeated in publications ever since.

Other factors besides weak water pressure contributed to the extent of the disaster. No doubt lingering smoke from forest fires delayed widespread awareness of the fire. The blaze started in a trash-ridden area of flimsy wooden structures. There was no citywide siren system. The pumping station had no telephone. The volunteer firefighters had inadequate leadership, were poorly equipped, and had to haul their own hose carts.

After the fire, the city prohibited wooden structures in or near the newly rising downtown, installed an electric fire alarm system, and established a professional, paid fire department, with horse-drawn equipment. Spokane rebuilt quickly, and a new city rose from the ashes.