Ezra Meeker (1830-1928) was a Washington pioneer, successful hops farmer, merchant, and an influential advocate for preserving the Oregon Trail. With his wife Eliza Jane Sumner Meeker (1834-1909) he founded the town of Puyallup on the land surrounding their small cabin. Meeker represented Washington Territory and later the state of Washington in several major expositions in America and abroad. From 1906 until his death in 1928 Ezra Meeker devoted the majority of his time and energy to ensuring that the old emigrant trail used by more than half a million pioneers from 1842 to 1869 was marked and preserved, and that the memory of those pioneers was venerated. Ezra Meeker's steady insistence that the emigrant route deserved preservation and persistent publicizing of this cause ensured that the historical phenomena and literal pathway now known as the Oregon Trail were not forgotten.

Early Years

Ezra Meeker was born December 29, 1830 in a log cabin on the family farm near Huntsville, Ohio. His mother was Phoebe Baker Meeker and his father was Jacob Redding Meeker. In 1839 the family moved to Indiana near Indianapolis to farm.

Although he had only six months of formal schooling, Ezra Meeker was an avid reader, a true autodidact who read deeply on whichever subjects he was pursuing. He was a founder of both the Steilacoom Library and the Puyallup Library Association. On May 13, 1851, he married his neighbor, Eliza Jane Sumner, splitting 300 rails for the minister in lieu of paying him a fee. This enduring union would produce six children: Marion, Ella, Thomas (who died in infancy), Carrie, Fred, and Olive. Meeker later claimed never to have spent even one day sick in bed during his entire 58-year marriage.

Young Ezra and Eliza spent the bitterly cold winter of 1851-1852 on a rented farm near Eddyville, Iowa, then in early April 1852 loaded a covered wagon and joined the more than 50,000 people who made up the 1852 emigration to Oregon Territory. Eliza Meeker had given birth to a son, Marion, only seven weeks before. William Buck, a slightly older acquaintance of the Meekers, and the Thomas McAuley family completed the wagon party. Meeker's older brother Oliver (1828-1860) and friends of his joined them at the Missouri River.

The Buttermilk! What a Luxury!

Meeker attributed their successful trip to Eliza's excellent planning and cooking skills, noting in Ox Team Days Or The Old Oregon Trail, written by Meeker in 1906 and revised and edited by Howard Droker in 1932, that in addition to butter, flour, cornmeal, eggs, dried pumpkin, fruit, and jerked beef, Eliza "had prepared the homemade yeast cake which she knew so well how to make and dry, and we had light bread to eat all the way across. We baked the bread in a tin reflector instead of the heavy Dutch oven so much in use on the plains ... Then the buttermilk! What a luxury! I shall never, as long as I live, forget the shortcake and cornbread, the puddings and pumpkin pies, and above all, the buttermilk" (p. 30). Meeker implies that their cows continued to give milk throughout the journey, making the Meekers a fortunate exception to the usual story of emigrant privation.

Despite ample provisions, by the time the group reached Portland five months later Eliza Meeker was ill and Ezra had lost 20 pounds. Oliver had survived a bout of cholera, a disease that killed scores of emigrants to the Oregon Country.

Rooted and Uprooted

Oliver and Ezra ran a boarding house in St. Helens, worked as loggers and longshoremen on the Columbia, and then filed homestead claims in Kalama where Meeker built a cabin. In the spring of 1853 the Meeker brothers explored the coastline from Olympia to Port Townsend, eventually settling on McNeil Island. In January 1854, Oliver traveled back to Ohio via the Isthmus of Panama to help their parents emigrate. In August 1854, Ezra Meeker received word that the party was stalled on the trail without provisions. With great difficulty, he made his way over the Naches Pass Trail, which had been blazed in 1853. Upon locating his family, he learned that his mother had died in the Platte Valley and been buried along the trail. Death had also taken Meeker's younger brother Clark, who drowned in the Sweetwater River and was buried near Independence Rock in what would later become Wyoming.

Jacob Meeker encouraged Oliver, Ezra, and Eliza to abandon McNeil Island and settle on the mainland. Meeker moved his young family to Swamp Place near Fern Hill (southeast of Tacoma). During the Yakama Indian war of 1855 they sought shelter at Steilacoom, where Ezra, Oliver, and Jacob built a blockhouse and opened a general store called J. R. Meeker and Sons. After gold was discovered on the Fraser River in Canada in 1858 they opened a branch in Whatcom and profited greatly by selling provisions to hopeful miners.

In 1857, Meeker served on the in the first trial of Nisqually Chief Leschi (1808-1858). Leschi was accused of the "murder" of American Colonel A. Benton Moses, who was killed in battle. Meeker and fellow juror William Kincaid voted to acquit Leschi, resulting in a deadlocked jury. A second trial, which did not include Meeker on the jury, was convened in Olympia, and Leschi was convicted. Some sources assert that Meeker always maintained Leschi's innocence, whereas others question that assertion (see "Mass Meetings of the Citizens of Pierce County, W.T.," Pioneer and Democrat, February 12, 1858, and William Bonney's 1927 account of that meeting).

In 1861 Oliver traveled by ship to San Francisco with all of their savings to buy stock for their stores. On his return trip, his ship, the Northerner, sank off the coast of California. Oliver drowned and all the goods were lost, leaving the remaining Meekers both heartbroken and penniless. The farm at Swamp Place was also a failure: the soil proved too poor for to raise a crop.

All Hopped Up

In 1862 Ezra and Eliza moved with their four children to the Puyallup Valley. They took over a small cabin on a claim that had been abandoned by Jerry Stilly. Eliza planted ivy near the cabin door and the vines soon grew to cover the little home.

In 1865 Meeker and his father planted hops from shoots grown by Charles Wood in Olympia and watched them flourish. The Puyallup Valley seemed ideally suited to the cultivation of hops vines, which produce hops flowers that are dried and used to flavor beer. Meeker's hop business was so successful that he established a branch office in London to sell hops on the world market. In 1884, 1885, 1886, and 1887 the Meekers spent four months a year in London. In 1885 Eliza was presented at court to Queen Victoria (1819-1901), wearing a dress made by a Puyallup dressmaker named Mrs. Fields, who had a shop on Meridian Street.

But then in 1892 a plague of hop lice struck the Pacific Coast, devastating crops. Meeker's crop sold for a fraction of the expected price. He later wrote, "All my accumulations were swept away, and I quit the business -- or rather, the business quit me" (Meeker and Driggs, p. 204). Beginning in 1868, Meeker ran a mercantile business in Puyallup, selling the operation to his eldest son, Marion, in 1884. Meeker's father, Jacob, who had remarried, died in 1869.

Promoting Washington Territory

In 1870 Meeker wrote an 80-page pamphlet, Washington Territory West of the Cascades, and on December 5, 1870, departed for New York to spread the gospel of Puget Sound's wonders. In addition to his pamphlet, he carried botanical specimens, gathered and classified by H. R. Woodard of Olympia, of 53 varieties of flowers in bloom in Washington Territory in December. He traveled down the Columbia River, then by ship to San Francisco, and finally via the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads, sitting up the entire journey since there were as yet no sleeper cars available.

He met with New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley (1811-1872) (famous for the phrase "Go west, young man") and financier Jay Cooke (1821-1905), who was at that time selling Northern Pacific Railroad bonds to finance the construction of that transcontinental line. Cooke bought all 2,500 copies of Meeker's pamphlet, using it as a sales tool, and also commissioned Meeker to tour New England drumming up interest in the Pacific Northwest. Cooke then hired Meeker to advertise the Northern Pacific from an office in Manhattan. While he was on the East Coast, Meeker pointedly dressed to Eastern standards, in starched shirts and a top hat, but he continued to surreptitiously doctor his coffee with a lump of butter as he was accustomed to doing at home.

In 1877 Meeker platted the town of Puyallup. When Puyallup incorporated in 1890, he was elected mayor, serving two non-consecutive terms.

From November 10, 1885, to April 1, 1886, Meeker served as commissioner of the Washington Territory exhibit at the American Exposition in New Orleans, Louisiana. The program for the event also lists Mrs. E. J. Meeker as Lady Commissioner and Miss Olive Meeker as Assistant Lady Commissioner. Meeker's many displays included a miniature hop house and a miniature of Snoqualmie Falls. By May 1, 1886, the Meekers were in London where Ezra represented Washington Territory at the Colonial and Indian Exposition.

Palace in Puyallup

Having now been presented to the Queen, Eliza Meeker was finished with living in a dirt-floored cabin. In 1887 she hired Tacoma architects Ferrell and Darmer to design and build a 17-room Italianate Victorian mansion a few blocks from the log cabin. The Meekers moved into the house in 1890. Over the 20 years the Meekers owned the house, Ezra was frequently absent for months or even years at a stretch and after Eliza's death on October 15, 1909, he dispensed with it as soon as he was able. In 1971 the Meeker Mansion, by then owned by the Ezra Meeker Historical Society, was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1891 Ezra Meeker was a founder of the Washington State Historical Society. He was active in the organization, serving as president in 1903-1904.

Clash with Meany

On May 20, 1891, Meeker was elected Executive Commissioner of the Washington World's Fair Association's committee, which was planning Washington's participation in the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago World's Fair). Almost immediately after his election, Meeker began to clash with Association press agent, state representative, and well-respected Washington booster Edmond Meany (1862-1935) over financial control of the organization. The feud received substantial coverage in newspapers statewide and resulted in Meeker's removal from the Executive Commissioner position on August 21, 1891. Meany was fully exonerated of Meeker's charges of financial impropriety. Meeker ultimately (and without full explanation) reversed his anti-Meany stance and withdrew his accusations in February 1893.

In 1896 Meeker traveled to Alaska, opening a store in Dawson and filing a mining claim. Despite four trips to the Klondike, he never found gold. In 1901 his son Fred, who was in Alaska with him, died of pneumonia and was buried there. Meeker abandoned his claim and returned to Puget Sound, arriving in Puyallup just in time to celebrate his 50th wedding anniversary with Eliza.

In 1903 Meeker began collecting notes for what would become his Pioneer Reminiscences of Puget Sound: The Tragedy of Leschi. The book's publication in 1905 sparked further public brawling with Edmond Meany on the pages of local newspapers. Meany objected to Meeker's stance that Indian Agent and Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) mistreated the Indians and grossly mishandled treaty negotiations. In Meeker's view, heavy drinking contributed to what he saw as Stevens's ineptitude.

Go East, Old Man

In 1906, at the age of 76, Ezra Meeker began retracing his 1852 Oregon Trail journey, this time heading east. Meeker's aim was to identify the trail's exact path, obscured by the passage of time, and to place historical markers along the route. The great overland migration over what came to be known as the Oregon Trail began in the 1840s and lasted into the 1870s, dwindling dramatically after the Union and Central Pacific Railroads completed the nation's first transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869.

During those years more than half a million people traversed the emigrant path that ended in what is now Oregon City, Oregon. (Meeker considered the Trail's end to be where he ended up, Puget Sound. The National Trails System Act of 2004 marks the beginning of the Oregon Trail as Independence, Missouri, and its end as Oregon City, Oregon.) Preserving and honoring the memory of those who made this arduous five-month journey, as well as the physical path, became Ezra Meeker's most enduring lifework.

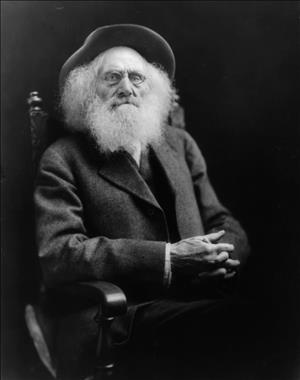

The very icon of an aged pioneer, Ezra Meeker and his anachronistic prairie schooner were front-page material. Contemporary photographs, many of them later printed on the postcards Meeker sold to fund his travels, depict a grizzled, feisty, skin-and-bones apparition with long white hair and a flowing beard. Bystanders who were captured in these images watching Meeker look both fascinated and bemused.

Continuing to the East Coast after reaching the end of the trail, Meeker's oxen and wagon literally stopped traffic as he crossed the Brooklyn Bridge, made his way through lower Manhattan toward the New York Stock Exchange, or in Washington, D.C., parked his rig in front of the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue to stand conferring with President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), casually motioning toward the wagon wheels. Ever-increasing coverage in major newspapers kept Meeker and his Oregon Trail cause in the public eye for two decades.

Meeker made four official Trail-promoting trips. The first lasted from January 29, 1906, until June 6, 1908. The return portion of this trip was made by rail, often shadowing the path of the Oregon Trail. Meeker made a second trip from March 16, 1910, until August 26, 1912. Over the course of his two wagon-journeys, Meeker placed 150 markers along the trail, usually partially funded by local subscribers, involving local historical societies wherever possible.

Meeker made a third trip from May 12, 1916, to September 16, 1916, this time going east to west in The Pathfinder, a touring car with a wagon-like canvas shell on top. Meeker used this third trip primarily to lecture on the need for and military value of a national highway. Before departing he met with President Woodrow Wilson, who endorsed the idea of a national highway. Meeker proposed a transcontinental highway that was to be called the Pioneer Way. The highway would have covered the route of the Cumberland Road (also called the National Road) from Cumberland, Maryland, to Vandalia, Illinois, and the Oregon Trail. In October 1924, he flew over a portion of the trail in a single-engine, high wing Army Fokker T-2. By ox, Meeker made two miles per hour crossing the Trail. His plane flew the route at 100 miles per hour.

In 1909 Meeker operated a pioneer restaurant concession and memorabilia display, including the oxen and wagon he'd used on his first trail-marking trip, near the Pay Streak amusement area at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. By agreement with Fair Director General I. A. Nadeau, Meeker paid no fee for his display space. Meeker drove his oxen, Dave and Dandy, pulling the prairie schooner, onto the Exposition grounds to spectators' wild applause.

In 1915 Meeker represented Washington at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. He lectured and showed film footage of his trail-marking journeys and displayed his prairie schooner, along with Dave and Dandy, who had been slaughtered in June 1914 and preserved by a taxidermist. The overwhelmingly enthusiastic response of fairgoers, particularly children, prompted Meeker to travel throughout the Pacific Northwest speaking to school groups.

The Long Trail and the Wild West

During the 1920s, Meeker continued advocating for good roads and especially for a cross-country highway. By dint of his longevity and public profile, he had also become a prototypical Pacific Northwest character, his eccentricity both mellowed and enhanced by his years. In 1921 Meeker published 70 Years of Progress In Washington. In 1926 at the age of 96, Meeker published Kate Mulhall: A Romance Of The Oregon Trail, a work of fiction. Meeker also wrote several volumes of short stories for children.

In 1925 and 1926 Meeker appeared with the J. C. Miller Wild West Shows, demonstrating the proper way to drive an ox team. J. C. Miller was the largest Wild West show of the era. Meeker was touted as "the only living person who crossed the Oregon Trail as an adult and who, at the age of 95, crossed the continent again in an airplane" (Old Timer's Gazette).

In 1926 Meeker appeared on the new medium of radio. He later wrote, "They gave me the title of 'the world's oldest broadcaster.' I was happy that the privilege had come to me of using this new and wondrous invention to spread farther the story of the pioneers" (Meeker and Driggs, 286).

In April 1926, Meeker, then staying in New York, founded and became president of the Oregon Trail Memorial Association. He once again went to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress to create a special Oregon Trail coin. The coin was a 50-cent piece, but sold for a dollar, with the profit going toward paying for more trail monuments. Congress passed the bill on May 26, 1926, and President Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) signed it into law.

In the summer of 1928 Meeker became ill while visiting Henry Ford (1863-1947) in Detroit. Ford had made Meeker a special vehicle he called the Oxmobile, an automobile chassis fitted with a covered wagon top, and Meeker had been planning yet another trail journey. Meeker spent several months in the Ford Hospital, and was then loaded onto a Pullman car for the three day trip home by rail.

End of the Trail

Ezra Meeker died on December 3, 1928, in room 412 of the Frye Hotel in Seattle. He was 27 days shy of his 98th birthday. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that as he lay dying, two chartered airplanes flew above the Frye loaded with coastal rhododendrons, Washington's state flower. As the planes soared over the hotel they "dipped their wings in salute and the pilots released their blossoms, which showered the hotel and the crowds in nearby streets" (December 4, 1928).

In the days preceding his death The New York Times published frequent bulletins on his condition. Already a stalwart Pacific Northwest pioneer at the time he took up the cause of Oregon Trail preservation, Ezra Meeker had become a household name throughout the nation during his final two decades. As a symbol of the epic American pioneer to the many who read newspaper stories about his exploits, as the self-appointed spokesman for the men and women who walked the emigrant road and for the dead they buried along the way, and as the living embodiment of pioneer grit and endurance to the hundreds of thousands of people of all ages who saw him in person, Meeker was legendary.

The Washington State Historical Society filled Meeker's famous covered wagon with an enormous floral wreath and meat packer Charles Frye (1858-1940) secured the services of a prize show pair of oxen to pull the wagon to the Hamilton Mortuary in Puyallup, where Meeker's body lay. Hundreds of mourners, among them many schoolchildren whom Meeker had met in his educational visits to Washington classrooms, filed past the bier. A funeral service at Westminster Presbyterian Church followed.

Meeker was buried beside Eliza Jane in Puyallup's Woodbine Cemetery. Bringing his trail-marking activities home to rest, in 1939 the Oregon Trail Memorial Association erected a marker engraved with a covered wagon drawn by two oxen over the pair of graves. Although the Meekers' tiny cabin in Puyallup was gone by the early twentieth century, the ivy Eliza Meeker planted near the front door still flourishes in Puyallup's Pioneer Park, trained over a pergola that marks the site of Ezra and Eliza Meeker's first Puyallup home.