Grays Harbor County takes its name from the broad, shallow bay that drains five rivers in southwest Washington. The dense forests of spruce, hemlock, cedar, and Douglas fir attracted loggers and mill operators and at the turn of the twentieth century, communities such as Aberdeen, Hoquiam, Cosmopolis, and Montesano flourished. Immigrant wage earners flooded in to harvest green gold. One hundred years later, the county struggled to reinvent itself without logging, milling, and fishing. The Native Americans who were shoved aside by the settlers reemerged with self-government and new enterprises.

First Peoples

The original residents of what would become Chehalis, then Grays Harbor County, were members of the Quinault Tribe along the coast north of Grays Harbor and the Chehalis of the lower Chehalis River drainage. Other tribes in the area included the Queets, Humptulips, Satsop, Wynoochee, and Copalis. By Quinault tradition, the Great Spirit called all the animals together and described how he would place humans on the earth. These he called Quinault. The Chehalis, Quinault, and Hoh tribes spoke a Coast Salish language closely related to other Salishan language groups in the Northwest, but unlike that of the Chinooks to the south or the Hoh and Makah to the north. All the tribes also used a trade jargon called Chinook.

The Grays Harbor area tribes lived in permanent villages along rivers and lakes. Water defined their economic and cultural lives. They harvested salmon as the anadromous species swam upstream to spawn, as well as whales and seals along the coast. In the summers, hunters ranged inland and into the Olympic Mountains for game and to trade with other tribal groups. The Indians developed a high degree of skill with canoes carved from cedar trees in a variety of specialized designs adapted to swift-flowing rivers, broad estuaries, and the sea.

Contact

The largest village in the area was at the mouth of the Quinault River and was so named by English fur trader Charles William Barkley in 1787. This later became Tahola after Taxola, the Quinault chief in 1855. The Quinault's first contact with Spanish explorers in 1775 near Grenville Point ended in the deaths of seven Spaniards and as many as seven Indians. The Indians had traded peacefully with the explorers, but turned on them after the Spaniards landed, erected a cross, and claimed the land for the Spanish king. The reason for the sudden attack remains unexplained, but tribal historians have offered the possibility that the Europeans had violated a women's safe haven.

The coastal tribes traded with and raided upon their neighbors and the acquisition and traffic in slaves pervaded the indigenous cultures. Contact with Europeans and the frequent interaction between tribes accelerated the several epidemics that swept the region beginning with smallpox in the 1770s and continuing with what was likely malaria in 1829, cholera in 1836, and smallpox again in 1853. The native population dropped from thousands to a few dozen. So many Chinooks died around Willapa Bay in the 1850s that the Chehalis moved in to take their place.

Treaties

In 1855, the Quinault, Hoh, Queets, and Quileute tribes signed the Quinault River Treaty with the Washington Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862) ceding 1.2 million acres of the Olympic Peninsula to the United States in exchange for a common reservation and fishing rights. The reservation was expanded by Congress in 1873, but the practice of granting allotments to individual tribal members resulted in 93 percent of the reservation passing into non-Indian hands (alienation). Non-treaty Chinook, Chehalis, and Cowlitz tribal members were also allowed to apply for allotments, which were often then sold to timber companies. On March 22, 1975, the members formed the Quinault Indian Nation with headquarters in Taholah.

The Chehalis Tribe received a 4,214-acre reservation in eastern Chehalis County in 1864 near what would become Oakville. In 2003, this was 1,952 acres governed by the Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation.

Arrival of the Americans

On May 7, 1792, Boston fur trader Robert Gray crossed the bar into the bay he called Bullfinch Harbor, but which later cartographers would label Chehalis Bay, then Grays Harbor. Irishman John Work (Wark) (b. 1792) of the Hudson's Bay Company explored the area in 1824. English botanist David Douglas paddled down, then back up the Chehalis River in 1825. U.S. Navy Passed Midshipman Henry Eld Jr., of the U.S. Exploring Expedition under Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, mapped the Chehalis River, Grays Harbor, and the coast down to Cape Disappointment in 1841. Eld was unimpressed with Grays Harbor because of the narrow entrance and its shallow bottom, suitable only for small vessels.

The county’s first permanent white settler was Irishman William O’Leary (1821-1901), a recluse who supplied several stories as to his origins. He paddled and trekked overland from Oregon to the Chehalis River, then by canoe down to the future site of Cosmopolis, just above the river’s outlet into Grays Harbor. O’Leary planted potatoes and a vegetable garden, and built a split-cedar cabin in the style of the local tribal peoples. While others built farms, businesses, industries, and towns, O’Leary was content to grow and gather his own food and cut his own hair. He remained fiercely independent and was regarded by his fellow citizens as an "odd character" (Van Syckle, River Pioneers, 81).

In the 1850s, more settlers occupied the country drained by the Chehalis River, but many filed Donation Land Claims only to move on to other opportunities without proving up their claims. Mainer Isaiah L. Scammon and his wife Lorinda (Hopkins) Scammon built a home on their Donation Claim at the head of tidewater (the limit for sailing ships could navigate up the river without assistance). This was a point convenient for river travelers to stop for the night and the couple operated a public house there. Scammon practiced his blacksmith trade for the next 36 years as well as serving as a postmaster, judge, church leader, and school administrator.

It was Lorinda who named the claim Mount Zion, following her deep religious convictions, and later changed it to Montesano, meaning Mountain of Health. In 1854, the Territorial Legislature created Chehalis County encompassing most of southwest Washington. The legislators placed the county seat at Bruceport on Willapa (Shoalwater) Bay, very remote for the Chehalis River settlers. In 1860, the Legislature settled the boundary between Pacific County and Chehalis County. On July 9, 1860, 74 men paddled and trekked to Chehalis Point to vote for a new county seat. The votes were counted back upriver at Scammon’s, which received a plurality of 33 votes in favor of placing the seat at there. For 26 years, Lorinda Scammon’s parlor was the county seat.

Grays Harbor County

Charles N. Byles (b. 1844) of North Carolina purchased acreage north of Scammon’s in 1870 and platted the city of Montesano. By 1881, the community boasted homes and businesses. In 1886, residents of Cosmopolis on Grays Harbor pitched to move the county seat from Scammon’s to their town. Montesano and its Chehalis Valley Vidette campaigned for themselves. Montesano won and Byles donated the land for the Chehalis County courthouse.

By 1900, Aberdeen and Hoquiam were home to 80 percent of the county's population thanks to their access to the sea for the region's principal product, timber. In 1905, leaders of the two rival communities combined to move the courthouse to one of their cities. This failed, so they campaigned to split the county in two, the west half becoming Grays Harbor County. One main opponent to the proposal was the Weyerhaeuser timber company, which owned thousands of acres of land and feared higher taxes. Company employees signed petitions against the division or faced being fired.

In March 1907, the State Legislature enacted a law dividing the county. Weyerhaeuser and Montesanans took the matter to court and the issue bounced around the legal system for two years. The one-county partisans prevailed. In 1915, the secessionists gained some satisfaction when the county changed its name to Grays Harbor. (This also eliminated some confusion since the city of Chehalis was in Lewis County.)

Mill Towns

In 1880, Charles Stevens converted his water-powered grist mill at Cosmopolis to a sawmill and the following year shipped Grays Harbor's first load of lumber to the world. By 1885, mills opened at Hoquiam and Aberdeen. In 1890, 13 mills filled 256 vessels with 66 million board feet of cut lumber.

Sol Simpson's Puget Sound & Grays Harbor Railroad from Shelton in Mason County reached Elma and Montesano in the 1880s to haul logs. A Northern Pacific (NP) subsidiary acquired the line from McCleary to Montesano and connected to the Norther Pacific system. Towns on Grays Harbor vied for the next extension, which would be the key to prosperity and even wealth. In March 1890, the Northern Pacific Railroad identified Ocosta on the south shore of the bay as its terminus and Ocosta experienced a land boom. When NP officials rethought Ocosta, they dangled the idea of a terminus in front of Aberdeen. But the sharp terms offered by the railroad and then the Panic of 1893 delayed the project.

Under the leadership of Aberdeen founder Samuel Benn (b. 1832), city fathers decided to build their own line from Aberdeen to Montesano. They used rail salvaged from a shipwreck, ties contributed by local mills, volunteer labor, and donated building lots. Aberdeen citizens turned the new line over to the NP and the first train arrived on April 1, 1895. The rails reached Hoquiam, just over the Wishkah River to the west soon thereafter. In 1909, the Oregon Washington Railroad & Navigation Company, with connections to the Union Pacific and the Milwaukee Road, gave Aberdeen and Grays Harbor access to three transcontinental railroads. A light at the entrance to the harbor in 1898 improved maritime safety.

The Pope and Talbot Lumber Company and its subsidiaries and the Northern Pacific Railroad came to dominate the economy. According to journalist and historian Robert A. Weinstein, "From its forming days until well into the early 1900s Grays Harbor country should be described as a huge, profitably run company town" (Weinstein, 16).

With mills and shipyards humming along the shore and steam whistles screaming in the woods, Grays Harbor County boomed. Immigrants from all over the world flocked to jobs offering cash wages. But dreadful living and working conditions in the mill towns and logging camps provoked workers into organizing unions. Workers called Cosmopolis "the Western Penitentiary" (Weinstein, 19).

The skilled trades organized the first bargaining units, which shunned unskilled industrial workers. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) offered membership to all and the union easily signed up loggers and mill workers. In 1912, mill workers successfully struck county mills. The following year, loggers walked out, but the employers retaliated. After two months and no contract, the strike folded.

When the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, the IWW organized a statewide lumber strike to protest the conflict, which they viewed as victimizing working men. Federal and state officials rounded up organizers for committing sedition and some loggers found themselves in the Army’s Spruce Division. The war and the Red Scare that followed dealt organized labor a serious blow. The unions gradually bounced back, but the industry did not.

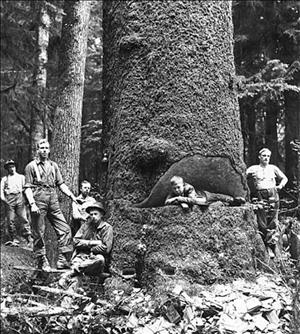

Decline of an Industry

Beginning in the 1920s, the wood-products industry -- logging, milling, and pulp manufacture -- started a long, slow decline. Most timber was cut from private land and once property was logged off, it was often abandoned to be taken by the County for unpaid taxes. As the old-growth trees were used up, logging companies and the mills gradually closed. The collapse of the housing industry during the Great Depression (1929-1939) left more mills silent. Anticipating the end of old-growth harvests, Weyerhaeuser opened its first tree farm near Montesano in 1941. Congress passed the Forest Practices Act in 1946, which hoped for a sustained yield by managing the harvesting of National Forests in concert with the replanting of private lands.

Beginning in the 1960s, the economic boom in Asia placed a great demand on Washington trees. Mills in Japan (subsidized by their government) could outbid local mills for logs and mill workers watched their livelihoods loaded on ships. As much as 40 percent of Washington’s wood-processing capacity dissolved between 1965 and 1975.

The recession of 1980 to 1985 resulted in automation at older mills and a weak U.S. dollar made British Columbia lumber cheaper than domestic supplies. In the 1980s, federal officials started limiting the sale of trees from public land to protect the Northwest Spotted Owl. The controversy pitched environmental protection against jobs and communities. The amount of timber cut from public land fell to less than a quarter of its past levels. In the 1990s, protections for the owls were extended to private lands. The government listed salmon as a threatened species in 1999 limiting further areas to be logged.

Fishing suffered from depleted runs. From 1976 to 1988, the Coho salmon catch dropped from 1.38 million to 74,000. "Digger trips" (The Seattle Times, September 19, 1993) for razor clams plummeted from 749,000 in 1967 to 32,000 in 1993. Unemployment in Grays Harbor County hovered at double the state average for the last three decades of the twentieth century. In the 1980s, the county population declined by 3 percent.

Life after Lumber

Beginning in 1978, a plan by the Washington Public Power Supply System to construct two nuclear power plants at Satsop -- designated Plant 3 and Plant 5 -- brought some short-term prosperity. As many as 3,500 people constructed two 496-foot cooling towers, reactor buildings, and the steam-powered generating plant. When projected costs doubled and tripled, WPPSS directors cancelled Plant 5 in 1982 and mothballed Plant 3. In 1994, Plant 3, 75 percent complete, was likewise cancelled. Plant 3 alone could have supplied the electricity needs of Seattle. In 1999, the WPPSS and the State gave the site with its buildings and a sewage treatment plant and $15 million to convert it to a business park. By 2005, 400 people worked there in a variety of industries.

The turn of the twenty-first century saw some new opportunities. The $195 million prison at Stafford Creek housing at least 1,900 inmates, employed close to 600 people, beginning in 2000. The Quinault Tribe opened a casino and resort complex at Ocean Shores in 2000. The natural wonders of Olympic National Park, charter fishing and the ocean beaches brought in other tourist dollars.

In 2005, Grays Harbor County was home to 69,800 people who were 88 percent white, 5 percent Hispanic, and 5 percent Native American.