Pacific County, named after the Pacific Ocean, is perched at the southwestern corner of Washington state. The ocean forms its western border and the north shore of the Columbia River and Wahkiakum County form its southern border. Grays Harbor County lies to the north and Lewis County to the east. A distinctive geographical feature is the 30-mile-long Long Beach Peninsula, which meets the ocean on its western side and shelters Willapa Bay on its eastern side. In 1851 Pacific County was the third county created in what would become Washington Territory. The economic base of the area's indigenous Chinook and Lower Chehalis peoples as well as of early-arriving settlers was oystering, especially in Shoalwater (later Willapa) Bay, and fishing. Soon lumber became a predominant early industry, followed by cranberry farming, dairy farming, and later, vacationing and tourism. Pacific County's area is nearly 1,000 square miles and the 2005 population was about 21,000 people. The county's four incorporated cities are Raymond, South Bend, Long Beach, and Ilwaco. Of the 39 Washington counties, Pacific County ranks 28th in population and 30th in land area.

Geography

Pacific County lies within two geographic subregions of Washington state known as Coastal Plains and the Coast Range. The coastal area consists of a sandy plain characterized by "shallow bays, tidal flats, delta fans and low headlands" that lie between the ocean and the foothills of the Coast Range (Pacific County Agriculture). Long Beach peninsula has one of the longest continuous ocean beaches on the on the Pacific Coast. It is one-to-three miles wide and 30 miles long. The interior side of the peninsula contained bogs, shallow ponds, and lakes.

Inland from the coast, the foothills were heavily forested with western hemlock, Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, western red cedar, and Pacific silver fir. The main hardwood trees are red alder and bigleaf maple. The climate is mild and damp but too cool and cloudy for most crops.

First Peoples

The Chinook Indians were original inhabitants of the lower Columbia River including the future Pacific County. There were more than 40 Chinook settlments in Pacific County, at the mouths of the Nemah, Naselle, Willapa, and Bone rivers, and at Nahcotta, Oysterville, Goose Point, Bruceport, Tokeland, and Grayland. The site of one of their main villages became Chinook.

Along with the Lower Chehalis, the Chinook wintered along Shoalwater Bay. They spoke the Chinook language and traded (mostly fur, fish, and slaves) over thousands of miles with many different peoples. They were master navigators of sea-going canoes, and salmon and oysters formed the core of their economic base. Reflecting their long experience as traders, their name was given to the Chinook Jargon, a trade lingo that included terms from Chinook, English, French, and Nootka.

The Chinook and the Chehalis were eventually decimated by introduced diseases. Many of their descendants, by accepting 80-acre allotments on the much larger Quinault Reservation, attained the privilege of Quinault treaty rights.

The Shoalwater Indian Reservation, consisting of 334.5 acres, was established by an executive order signed by President Andrew Johnson on September 22, 1866. Pacific County's only reservation, it occupies 333 acres on the north shore of Willapa Bay, on the site of an ancient Chinook village. The non-treaty Indians of Shoalwater Bay made their living by fishing, crabbing, and oystering, selling their surplus to canneries much the same as non-Indians. Members of the present-day Shoalwater Bay Tribe are descended from Chinook, Chehalis, and other area tribes. The tribe has 237 enrolled members and a resident service population of 1,148. The tribal center at Tokeland serves both the tribe and the surrounding community.

More than 1,000 Chinook tribal members live at Bay Center on Willapa Bay and in South Bend -- both ancient village sites -- and elsewhere around the region. The tribe has headquarters in Chinook, and continues to seek federal recognition.

Exploration

Pacific County's location on the Pacific Ocean and on the northern shore of the estuary of the Columbia meant that for early explorers arriving by sea, its bays and forested hills often became their first glimpse of the future state of Washington. Bruno Heceta, aboard the Spanish frigate Santiago, mapped the entrance to the Columbia River in 1775. Thirteen years later, in 1788, the British trader John Meares (1756?-1809), aboard the Felice Adventurer, traded with Indians off what is now called Willapa Bay. He did not actually find the river he was looking for and in his disappointment renamed Cape San Roque as Cape Disappointment and Assumption Bay as Deception Bay.

In 1792, British Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver viewed Cape Disappointment as a “conspicuous point” not worthy of investigation, and passed on by. On May 11, 1792, Captain Robert Gray of Boston aboard the Columbia Rediviva sailed into the Columbia River as the first European to do so. Here he encountered Chinook Indians in cedar dugouts with furs and fresh salmon to trade.

The Lewis and Clark expedition first viewed the Pacific Ocean from the sandy beach of the Long Beach Peninsula on November 15, 1805 (after mistakenly thinking a few days before that the rough waves of the Columbia were ocean waves). They arrived at the Chinook’s summer fishing village and stayed 18 days exploring the area. Considering the rain and fog, the party voted to winter on the other side of the river. Thus the future Pacific County was the site of the first election by Americans in the West and the first to include a Native American and a woman (Sacagawea, the Shoshone wife of of one of the expedition's hunters) and an African American (York, Captain Clark's African slave).

At Astoria, across the wide river mouth from the future Pacific County, the American John Jacob Astor established a fur-trading post in 1811, which was by 1813 owned by the Canadian (British) North West Company, and by 1821 by the British Hudson's Bay Company. Extensive trading and familial relationships developed between the Chinook and these British fur traders.

Under Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, the U.S. Exploring Expedition arrived in the summer of 1841. One of the expedition's vessels, the Peacock, sailed the into the mouth of the Columbia on a survey mission, grounded on a sand spit, and was lost, giving its name to Peacock Spit. The crew was saved by nearby Hudson's Bay Co. fur traders and by missionaries. Among those who jumped ship was James DeSaule, the Peacock's black Peruvian cook. He became one of the first non-Indians to settle in the region.

Graveyard of the Pacific

The many shipwrecks at the mouth of the Columbia -- around 2,000 since 1792 -- have given rise to the name "graveyard of the Pacific." It was back and forth over this treacherous estuary that skilled Indian navigators guided their canoes, causing Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition to note their remarkable navigational skills “thro emence waves & Swells” ("18 Days in Pacific County").

More than one early settler in the area arrived by shipwreck. In 1829 the Isabella, bound for the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver, wrecked on a shoal. Thus arrived Englishman James A. Scarborough (1805-1855), who in 1843 settled at Chinook Point on the Columbia River. He married a Chinook woman, Ann Elizabeth, and filed a Donation Land Claim for all of Chinook Point and most of Scarboro Hill. He occupied the property until his death in 1855. The land ultimately became Fort Columbia, part of the U.S. Army’s defense of the mouth of the Columbia River. It is now Fort Columbia State Park.

In 1845 a marker was made by cutting off the tops of three fir trees on the crest of the headland, to be used as a navigational aid. In 1856 a lighthouse was built on Cape Disappointment. It was visible 21 miles out to sea, and had a fog bell. The U.S. Army mounted smooth-bore cannon at Fort Cape Disappointment in 1862 (or 1864). Renamed Fort Canby in 1875, the facility continued to serve in defense of the Columbia River until World War II. It is now part of Cape Disappointment State Park.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began dredging the mouth of the Columbia in the 1870s, and still dredges up four to five million cubic yards of sand every year. In 1980, the U.S. Coast Guard opened its National Motor Lifeboat School at Ilwaco. Today, the Coast Guard's related Station Cape Disappointment responds to 300 or 400 maritime calls for assistance each year.

The Confluence Project, unveiled in 2006 at Cape Disappointment State Park, is a $15 million monumental public-art project to commemorate stops by Lewis and Clark in Washington and Oregon. Designed by artist Maya Lin, the project offers lessons in history, celebrates indigenous cultures, and rehabilitates parts of the natural environment.

Formation and Settlement

From 1818 to 1846, the Pacific Northwest, called Oregon, was jointly occupied by Great Britain, represented mostly by Hudson's Bay Co. fur trappers, and by the United States. The first two counties in the future Washington state were created in 1845 by the Provisional Government for Oregon Territory, a body consisting of both British and American settlers. These were Clark (originally named Vancouver) and Lewis. In 1846 Great Britain ceded to the United States the Pacific Northwest below the 49th parallel and in 1848 Congress created Oregon Territory (including Washington and Idaho). The Oregon Territorial Legislature created Pacific County out of the southwestern corner of Lewis County in 1851. Pacific County was thus the third county formed in what would become Washington Territory, and the first formed by the Oregon Territorial Legislature. In 1853 Congress created Washington Territory, comprising Pacific, Lewis, and Clark (renamed Clarke) counties. Pacific County's boundaries were adjusted in 1860, 1867, 1873, 1879, and finally in 1925.

Settlement in the future Pacific County was framed first by nearby Hudson's Bay Co. fur trappers, and after 1848, by the California Gold Rush. This last caused San Francisco to boom and opened a large market for both lumber and oysters. Pacific County, accessible to San Francisco by sea, had both in abundance.

The promotional activities of Elijah White, who hoped to found a great port city on the Columbia, resulted in the new town of Pacific City, located just south of present-day Ilwaco. On February 26, 1852, a federal executive order set aside 640 acres at Pacific City for a military reservation and required residents to leave. By 1858 all that was left of Pacific City was a couple of houses and a sawmill.

Washington Hall, who had surveyed Pacific City for Elijah White, promoted his own town, Chinookville, beginning in April 1850. Despite the Chinooks' resentment of his appropriation of the site of their principal village, settlers elected Hall county commissioner and Chinookville became Pacific County's first county seat. Hall sold lots until July 1855, at this time deeding his worldly goods to his two children, whose mother was a Native American woman to whom Hall was not married. This protected him from challenges to his claims. He continued for five years to sell lots on behalf of his children, sometimes for cash and sometimes for goods such as shingles and salmon, before disappearing in the direction of Idaho.

Shellfish and Fish

During the 1850s, schooners began arriving in Shoalwater Bay, mostly from San Francisco, looking for oysters. One of these was the Robert Bruce. On December 11, 1851, the ship’s cook doped the crew and set the ship on fire. Bill McCarty, who was cutting timbers at Hawk’s Point, along with the Indians he was working with, carried the men ashore. The Robert Bruce burned to the water line. The stranded men, who in any case had come with the idea of starting an oyster business, settled on the bay, forming what became Bruceport. These “Bruce boys” entered the oyster trade and soon bought two schooners of their own.

In 1854, Chief Nahcati invited R. H. Espy, who had been cutting timber for the San Francisco market, and L. A. Clark, a New York tailor who'd achieved a modest success in the California gold rush, to the site of future Oysterville on the Long Beach Peninsula. There they filed Donation Land Claims and set up an oyster business, shipping canoeloads of oysters to Bruceport for shipment south. Soon vessels from San Francisco were arriving at Oysterville.

Oysterville founders also included the brothers John and Thomas Crellin, who also arrived in 1854. Enmity ensued between the two new oystering groups but this ended when John Morgan, one of the Bruce boys, married Sophia Crellin, sister of John and Thomas. The two companies joined forces and by 1863 were called Crellin & Company. From 1855 to 1892, the county seat was located in Oysterville.

The oyster trade brought one of Washington's earliest chroniclers to the Territory for the first time. James G. Swan (1818-1900) came to the future Pacific County at the invitation of his friend, oysterman Charles J. W. Russell. Swan lived on Willapa Bay from 1852 to 1855, observing the first pioneer settlement grow and getting to know the Chinook and Chehalis inhabitants, including Chief Comcomly's sister as well as Toke, the leader for whom Toke Point and Tokeland are named, and Toke's wife Suis. In 1857 Swan described Indian and pioneer life on the bay in The Northwest Coast, Or, Three Years' Residence in Washington Territory, one of the earliest books about life in Washington.

Native oysters fed San Francisco during the Gold Rush (1848-1864). After they were depleted, first eastern oysters (1893-1920) and then Pacific or Japanese oysters (1920s-1950s) were brought in and farmed. Finally, laboratories in the United States began to grow oyster spat (a minute oyster larva attached to a solid object, usually a piece of oyster shell), making imports no longer necessary. One out of every six oysters consumed in the United States is grown and harvested in Willapa Bay, the “Oyster Capital of the World.”

From the handful of companies farming the bay more than a century ago to the estimated 350 independent growers in Willapa today (many of them Japanese-Americans), Willapa Bay is thought to be the largest farmed shellfish producer in the United States.

Fishing and canning, too, have been essential to the economy. Salmon was one of the first items traded to early explorers. In 1853, Patrick J. McGowan, an Irishman, purchased 320 acres of an old mission grant and founded the town of McGowan on the north shore of the Columbia. Here he established the first salmon-packing company in the state.

Cranberries

Chinook Indians had long harvested the wild cranberries that grew in bogs, and as early as 1847 the berries were exported to San Francisco. In 1880, Anthony Chabot, a native of Quebec who had grown wealthy from engineering ventures in San Francisco, became interested in growing cranberries commercially. In 1881 he bought 1,600 acres of government land and planted 35 acres of cranberries at Seaview, near present-day Long Beach. He brought in several hundred thousand vines from Massachusetts, and production reached 7,500 barrels. Labor was provided by Indians and by Chinese. But eventually pests and mildew brought in with the non-native vines attacked the crop, labor problems developed, and the Chabot bog went to weeds.

Meanwhile another pioneer, Chris Hanson, had planted two acres of cranberries. For a time he was the only producer on the Long Beach peninsula. Between 1909 and 1916 cranberry growing increased there to 600 acres.

About 1912, a grower named Ed Benn introduced cranberries in the Tokeland and Grayland districts of northern Pacific County. Finnish settlers expanded the bog area.

In 1923 the State College of Washington (later Washington State University) established the Cranberry-Blueberry Experiment Station at Long Beach not far from Chabot's original bog to provide technical assistance to growers. Researcher D. J. Crowley worked out sprays to control pests, and overhead sprinkling to protect from winter frost and summer scald. WSU closed its Cranberry Research Station in 1992. Growers formed the Pacific Coast Cranberry Research Association in order to buy the station. They farm the former WSU bogs while WSU continues to support technical personnel.

In the 1930s growers associated with Ocean Spray, a co-op owned by cranberry farmers, to process and market their crops. Growers also affiliated with a national marketing association, the National Cranberry Growers Association. By 1957 the Washington cranberry industry was thriving. Today virtually all the cranberries harvested in the state, about 1.5 million pounds annually, are grown in the Willapa Basin.

Lumber

More than 90 percent of the Willapa uplands were forested. Approximately 3 percent of the present stands are undisturbed old growth with the majority of the remainder being managed timberlands. Mechanization of logging with steam locomotives and steam donkeys beginning in the 1890s made logging another mainstay of the county’s economy.

In 1892 the sawmill town of South Bend, located on the Willapa River, was named the county seat. The choice was so contentious that, in 1893, South Bend residents forcibly removed county records from Oysterville. Things remained calm for a number of years, until Raymond, an industrial town north of South Bend, took an interest in becoming county seat. To show Raymond how serious it was about keeping the county seat, South Bend built a new courthouse. Designed by C. Lewis Wilson and Co. in Chehalis, was nicknamed "the gilded palace of extravagance," which it was at the time.

Following World War I, the forest-products industry went into a long slow decline. Timber prices dropped in the 1920s and housing construction almost ceased in the 1930s. As the supply of old-growth timber from private lands declined, mills closed. Improvements in highway and rail transport made it possible to ship logs to large, distant mills, creating more pressure on local mills. A building boom in Asia beginning in the 1960s meant that Japanese mills could out-bid local mills for logs, leaving many local workers idle. Although timber sales from state and federal lands provided some jobs, the timber industry became a shadow of its former self.

In the 1980s Weyerhaeuser remodeled its Raymond plant, closed it, and reopened it with worker concessions. In 2001 the plant earned international recognition for its environmental management.

Dairy Farming

Dairy farms were established on stump farms in the hills after the trees were logged. In 1950 there were 150 dairy farms in the county. In 1964 the number of farms had fallen to only 40, but milk production had increased. In 2002 Pacific County had 341 farms with an average size of 152 acres.

Railroads and Roads

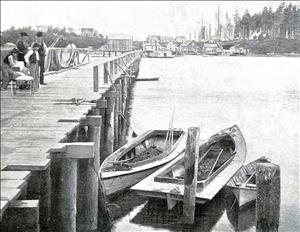

Lewis Loomis (d. 1913) owned the Ilwaco Navigation Company and the Shoalwater Bay Transportation Company. In 1888 he built a narrow-gauge railroad from Ilwaco to Nahcotta. Eventually it became part of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, and then a branch of the Union Pacific Railroad. The railroad took its final run on September 10, 1930.

The age of the auto arrived, and the Olympic Loop Highway (U.S. 101) that passes through Raymond and traces the shore of Willapa Bay, was completed in August 1931. The road made the beaches and products of Pacific County more accessible to the rest of the state. Thirty years later, in 1966, the completion of the Astoria-Megler Bridge spanning the Columbia River and connecting Oregon to Washington had a large impact on Pacific County.

Cities and Towns

The four incorporated cities of Pacific County are Raymond, South Bend, Long Beach, and Ilwaco. Tokeland is a quiet seaside village, the center of the Shoalwater Indian Reservation. Bay Center, located on the Goose Point Peninsula of Willapa Bay, is a center of fish farming. Its canneries prepare Dungeness crab, salmon, Pacific oysters, and Manila clams.

Raymond

Raymond, located on the Willapa River, was started in 1904 and quickly became a center of logging, an industrial mill town. A land company offering free waterfront tracts attracted some 20 manufacturing plants over the next few years. Its business section was originally built on stilts above the tidelands and sloughs of the site. Sawmills proliferated and German, Polish, Greek, and Finnish immigrants arrived to work in them. By 1905, 400 citizens lived in Raymond. The town, named after leading citizen and first postmaster Leslie V. Raymond, incorporated in 1907 and by 1920 had a population of 4,000. During World War I Raymond became a center of shipbuilding.

A notable Raymond firm is the Dennis Company, which started out as a shingle mill and in 1905, as prices dropped due to competition, merged with another mill, becoming the Raymond Shingle Manufacturing Company. This enterprise was blown to bits in a mill explosion later that year and the family turned to hauling firewood gathered from mill leftovers gathered from several companies. The transportation and sales business expanded into hauling coal, then blacksmithing, then moving pianos and furniture. The firm acquired a warehouse and began selling and delivering block ice. By 1925 it was selling and delivering ice, coal, wood, brick, lime, and cement. The Dennis family purchased forestlands and opened an alder mill to build (and deliver) furniture.

Possessing a transportation infrastructure, it was natural, when Prohibition was repealed in 1933, to go into delivery of beer and soda pop, which led to bottling and producing Dennis Quality Beverages such as Red Rock Cola. Eventually all this diverse activity led to opening a retail store in Raymond during the 1940s. Other activities included manufacturing cement, building houses, selling hardware and plumbing supplies, and operating a long-distance trucking business. The firm opened a feed store and a Honda shop, and went into the clothing business, starting with sweatshirts. Today it operates the original store and corporate offices in Raymond, as well as satellite stores in Aberdeen, Elma, Long Beach, and Montesano, plus a concrete plant in Ilwaco. The Dennis Company employs 100 people.

In 2006 Raymond is home to nearly 3,000 people. Manufacturing still provides about 14 percent of the employment. Health, education, and social services provide another 17 percent, as does arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodations, and food services.

South Bend

South Bend, down the Willapa River from Raymond, was founded in 1869. It was a lumber and sawmill town. In 1889, men associated with the Northern Pacific Railroad bought land there and within five years the town boomed from 150 souls to 3,500. The town went from boom to bust and back to boom several times, with fishing, oystering, canning, and the lumber business providing its economic base. In 1892 it became county seat and in 1910 erected the grand county courthouse, which was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

Today South Bend is a community of docks, fishing boats, crab-processing plants, and other enterprises and is home to the county historical museum. As county seat, South Bend houses numerous Pacific County government functions.

Long Beach

Tourists began arriving at the long beach that gives Long Beach its name in the late nineteenth century, attracted to what historian Lucile McDonald calls “Washington’s Cape Cod.” Long Beach, located on the southern part of the peninsula, triples in population each July and August. Tourists are mainly sport fishermen and fisherwomen and beach aficionados who surf, swim, eat oysters, shop, and fly kites (Long Beach is home of the annual Washington State International Kite Festival held the third week in August). In the 1990s Long Beach built a 2,300-foot-long dunes boardwalk, a network of wetland trails, and an interpretive center.

Long Beach was the approximate location of Anthony Chabot's pioneering cranberry operation. WSU's cranberry and blueberry experiment station was established here in 1923.

Long Beach has a population of about 2,300 residents. Hotels, motels, and bed-and-breakfast establishments, as well as gift shops, galleries, and restaurants serving visitors form an important part of the economy.

Ilwaco

Ilwaco, located at the southern end of the Long Beach peninsula, is a traditional fishing port. The town was also a center of logging and cranberry growing. The first non-Indian arrivals appeared in the 1840s, and included the American John Pickernell, who came from Champeog, Oregon, after French Canadian and American settlers there had disagreed over political organization. Another early arrival was James DeSaule, the black Peruvian cook on board the Wilkes Expedition's Peacock. DeSaule jumped ship when the vessel went down and eventually moved to Ilwaco and ran a freight service between Astoria (across the Columbia) and Cathlamet.

Ilwaco was originally named Unity in celebration of the end of the Civil War, but was always called Ilwaco, after Elowahko Jim, a son-in-law of the Chinook Chief Comcomly. A plat for the town was filed in 1876 under the name Ilwaco.

A Great Lakes method of trapping salmon led to a population boom to 300 after 1882. This involved traps made of tarred rope webs installed on permanent pilings and gave rise to conflict with gillnet fishers who found their fishing grounds preempted. The latter set nets afire, terrorized night watchmen, and in other ways tried to regain their fishing rights. The "gillnet wars" lasted from 1882 until 1910.

Ilwaco incorporated in 1890, and became a city nearly a century later, on July 13, 1987. It has a history museum, an 800-slip marina, a library, bookstore, coffeehouses and restaurants, an antiques store, and other businesses. The population of about 1,000 swells to 3,000 during the summer months when people come for swimming, boating, fishing, and other recreation.