William Edward Boeing started his professional life as a lumberman and ended as a real-estate developer and horse breeder, but in between he founded the company that brought forth important breakthroughs in the field of aviation technology and the airline business. The Boeing Airplane Company became one of the signature corporations of Seattle and the Pacific Northwest and dominated the regional economy for most of the twentieth century.

Early Years

William Edward Boeing was born on October 1, 1881, in Detroit, Michigan, the first child of William Boeing and Marie Ortmann. Boeing's father, Wilhelm Boing, a veteran of the Austro-Prussian War, emigrated to the United States in 1868 from North Rhine-Westphalia. He carried letters of introduction to German families in Detroit, but no money. After working on a farm, in a lumberyard, and in a hardware store, he was hired by Karl Ortmann, an important local lumberman from Vienna.

Boing married Ortmann's daughter and, five years later, started his own business. He was soon selling land, timber, and iron ore at huge profits and providing extraordinarily well for his wife, Marie, and two children, William and Caroline. Wilhelm Anglicized his name to William Boeing, built a stately home in Detroit's best neighborhood, acquired the city's finest library of German literature, and, in 1883, helped fund Detroit's first art museum. While in New York on business, Wilhelm Boeing contracted influenza. He died during the long trainride back to Detroit.

His son, William, was 8 years old. Marie Boeing married a Virginia physician and left Detroit. Young William, who did not get along with his stepfather, was sent to several prestigious boarding schools, including the Sellig Brothers School in Vevey, Switzerland -- the same school New York financier J. P. Morgan had attended 30 years earlier. Boeing attended a prep school in Boston to ready him for Yale University. He entered Yale in the engineering department of the Sheffield Scientific School.

After a year shy of completing the three-year program, he dropped out to seek his fortune saying later, "I felt the time was ripe to acquire timber." He decided on Washington state, even though he knew little about business opportunities in the Northwest and even less about timbering in the vast "Evergreen State." America was undergoing growth spurt and the nation demanded lumber for new homes and businesses and ambitious industrialists were reaping millions out of the seemingly limitless stands of cedar, spruce, hemlock, and Doug-fir.

Lumberman

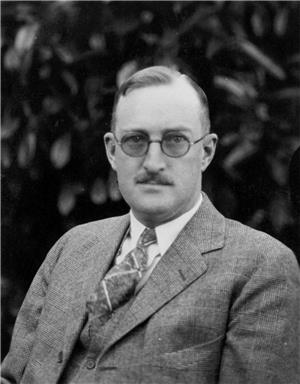

In 1902, Boeing traveled by steamer to Hoquiam, Washington, on Grays Harbor, and moved in with a friend, J. H. Hewitt, who had good connections in the timber industry. Within a short time, Boeing started the Greenwood Timber Company and the Boeing & McCrimmon Company. He was soon in touch with George Long, head of operations at Weyerhaeuser, trying to arrange land deals with the much larger company. Boeing left Hoquiam for Seattle in 1908 and the tall, bespectacled, mustached bachelor moved into an apartment on fashionable First Hill. He joined the University Club, an exclusive venue for college-trained men on their way up the Northwest business ladder.

In 1910, Boeing traveled with friends to southern California to witness America's first International Air Meet at Dominguez Hills. Excited by what he saw, he approached one of the show's stars, the French aviator Louis Paulhan, and pressed him for a ride. Paulhan told the man he had to be patient. After four days of waiting, Boeing lost his chance when Paulhan left in a rush.

Flying High

George Conrad Westervelt (1880-1956) graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, where he earned the nickname "Scrappy" for his ability to argue any subject. In 1910, after studying naval engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Westervelt served as an official Navy observer at one of America’s first air meets, in New York. Unlike many of his Navy colleagues, he was impressed with the new technology.

In about 1911, the Navy sent Westervelt to Seattle to inspect submarines being built at the Moran Brothers shipyard on the Duwamish River. He joined the prestigious Rainier Club and the University Club, where he met William Boeing. The two bachelors became friends, finding a shared enthusiasm for flying.

But five years passed before Boeing had another chance to take his first flight. When aviator Terah Maroney landed on Lake Union in 1915, Boeing and Westervelt stood in line and took several flights each. They had to sit on the wing and hold on to the leading edge while Maroney' old Curtiss airplane skipped across the choppy water and into the sky.

Exhilarated, Boeing decided to take lessons at the Glenn L. Martin Flying School in Los Angeles and he purchased one of Martin's planes. Martin pilot Floyd Smith traveled to Seattle to assemble Boeing's new Martin TA hydroaeroplane and to teach its owner to fly. Huge crates arrived by train, and Smith assembled the plane in a tent hangar erected on the shore of Lake Union. William Boeing became a pilot.

In 1915, World War I was raging in Europe, Africa, and Asia. Safe behind two oceans, most Americans did not feel threatened by the conflict, but William Boeing was one of a growing segment of the U.S. population that advocated "preparedness." Fourteen men and five women had formed the Aero Club of the Northwest in the Ladies' Annex of the University Club on August 24, 1915. William Boeing was elected president. From that point on, he was an ardent advocate for National Preparedness. He was also interested in the ideas of Henry Woodhouse, editor of Flying magazine, who had written, "With 5,000 aviators, this country would be in the position of the porcupine, which goes about its daily pursuits, harms no one, but is ever ready to defend itself."

In November 1915, Boeing spent a busy week in his new "hydroaeroplane." With test pilot and mechanic Herb Munter as his passenger, the lumberman flew to Tacoma and back to Seattle. He dropped cardboard "bombs" on a crowded California-Washington football game at the University of Washington to prove that Americans were vulnerable to foreign attack. One of the cardboard messages read:

"Protection Through Preparedness. This harmless card in the hands of a hostile foe might have been a bomb dropped upon you. Aeroplanes are your defense!!!! Aero Club of the Northwest."

That same year, even before becoming disappointed with his Martin TA, Boeing asked Westervelt to design a better seaplane. Westervelt wrote later, "I knew so little about the subject, so little about the difficulties involved, that I agreed to undertake it."

Airplane Builder

William Boeing and Conrad Westervelt believed they could build a better airplane than the Martin floatplane. For enhanced stability during landing and takeoff, they replaced the TA's single pontoon with two pontoons and two outriggers. Westervelt threw himself into the project, contacting every manufacturer he could find. Boeing and Westervelt chose Ed Heath to construct the pontoons at Boeing's boatyard on the Duwamish River. But shortly after Boeing's workers began work on the B&W -- for Boeing and Westervelt -- the Navy transferred Westervelt to the East Coast. He returned for a few weeks in August 1916 to help organize Boeing's new enterprise, Pacific Aero Products Co., which he aptly illustrated on a piece of drafting vellum.

Boeing and the tiny U.S. aviation community pressed the U.S. government to invest in airplane production and pilot training. An early Aero Club plan included Hydro-Aero stations positioned every 100 miles along the U.S. coastline, with at least 15 men and two planes each. They could protect the country by searching for enemy submarines and aiding the Coast Guard's search-and-rescue efforts.

Technical Challenges

Before Westervelt went east early in 1916, he arranged for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to review his structural drawings and to test a model in its wind tunnel. William Boeing proceeded with assistance from Herb Munter and shop foreman Joseph Foley, who sent weekly reports to Westervelt. The boatyard's standard of woodworking disappointed Boeing, who also insisted on reduced weight. Other change orders included an improved wing; ailerons on the top wing only; and larger vertical tail surfaces.

Boeing ordered construction of the fuselage at his company's seaplane hangar and factory on Lake Union. There employees assembled Boeing Airplane Model 1, also known as the B&W, and christened it the Bluebill. On June 15, 1916, the B&W flew for the first time. Eventually, Boeing sold the Bluebill and its sister aircraft, the Mallard, to the New Zealand Flying School of Auckland. Neither aircraft survives today, but a replica hangs in The Museum of Flight’s Great Gallery.

Founding a Company

On July 15, 1916, a month after the B&W's first flight, William Boeing incorporated his airplane-building business as Pacific Aero Products Company. Already a shrewd businessman, Boeing outlined his ambitions in the articles of incorporation. One of the articles allowed the firm to "... engage in a general manufacturing business and to manufacture goods, wares and merchandise of every kind, especially to manufacture aeroplanes ... and all patterns thereof." William Boeing transferred ownership of four of his aircraft -- two B&Ws, a C-4, and the Martin TA, as well as associated property -- to his company. On April 18, 1917, he changed the name to Boeing Airplane Company.

Before joining the Boeing Airplane Company, Edward "Eddie" Hubbard had already established his prowess as a pilot: The Aero Club of America had issued hydroaeroplane license no. 45 to him in 1915 after he flew figure eights around two pylons 500 yards apart and completed an unpowered landing. Americans celebrated the end of World War I in a big way on November 11, 1918. Hubbard marked the festivities by taking Boeing officials on stunt rides above downtown Seattle; engineer Louis Marsh rode through two loops. In early 1919, when the 91st Division returned to the Northwest from Europe for a parade in Seattle, Hubbard's air show delighted the crowd for 30 minutes.

An Industry Grows

William Boeing and Eddie Hubbard made aviation history in March 1919 when they flew to Vancouver, British Columbia, picked up mail and delivered it back to Seattle -- almost. Halfway through the trip’s northbound leg, snow forced an overnight stop in Anacortes. On the return trip, low fuel forced the duo to land 25 miles north of Seattle.

Boeing kept his company alive after World War I by building furniture and speedboats (popular on Puget Sound during Prohibition) and with personal checks. Military and naval contracts tipped the scales toward survival beginning in 1921. When the Congress gave up on the Post Office flying the mail (with 31 of the first 40 pilots killed) in 1925, and passed legislation to contract with private firms, commercial aviation became viable. Air Mail contracts made passenger airplanes possible. Eddie Hubbard convinced Boeing to get into the Air Mail business in addition to building the planes. Mail revenues of Boeing Air Transport underwrote passenger service and the development of navigational aids and airports. Airline operations justified the opening of the Boeing School of Aeronautics in Oakland, California, in 1929. By 1928, Boeing Air Transport held 30 percent of air mail and air passenger market in the United States.

But competitors threatened this share through consolidation. Boeing accepted an offer in 1929 to merge his airline and manufacturing business with engine supplier Pratt & Whitney, forming United Aircraft & Transport Corporation. Boeing became chairman of the board. Boeing Air Transport folded into United Air Lines.

Backlash

In 1930, U.S. Postmaster General Walter Brown used new legislation to modify airmail contracts in an infamous series of meetings with airline executives later called "the Spoils Conferences." By 1933, four enormous holding companies, among them United Aircraft and Transport, dominated American aviation at all levels. Despite the worldwide economic depression beginning in 1929, the airline and airplane business flourished and by 1933 the public and politicians resented what they viewed as corporate profiteering. The Democratic Congress, supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt"s administration, sought corporate scapegoats. William Boeing and United Aircraft & Transportation Corporation, along with the three other aviation giants, were convenient targets. President Roosevelt's reaction, over the protests of his Postmaster General Jim Farley, was to cancel all the airmail contracts and turn the Air Mail over to the Army Air Corps in February 1934.

In the first five weeks, 12 inexperienced and ill-equipped Army pilots died. William Boeing, who knew that he and his companies were innocent of any wrongdoing and were being unfairly sanctioned, agreed to testify before a Senate investigating committee chaired by Alabama Democrat Hugo Black. During the session, several congressman attacked Boeing personally, and the Seattle businessman became very bitter. Although the investigation revealed that neither the airline executives nor Postmaster Brown had done anything wrong, the Congress passed legislation banning aircraft manufacturers from owning or being owned by airmail carriers. Individuals who had attended the Spoils Conferences were specifically forced out of their jobs.

United Aircraft & Transport was divided into three main parts -- United Aircraft absorbed Pratt & Whitney, Sikorsky Aviation, and Hamilton-Standard Propeller; United Air Lines retained the airline; and Boeing Aircraft Company secured Stearman Aircraft in Wichita, Kansas, Boeing in Seattle, and Boeing in Canada.

William Boeing was already three years past a self-imposed plan to retire at age 50. He returned to the Northwest to sell his stock in United Aircraft & Transportation Corporation. Except for acting as a consultant during World War II, he never again took an active interest in the company bearing his name. The same year that the federal government forced Boeing out of the aviation business, he received the Daniel Guggenheim Medal for notable achievements in aeronautics, only the sixth man to be so honored. Aviation pioneer Orville Wright had received the first Guggenheim.

After the Aircraft Business

William Boeing turned to other business pursuits including real estate, Wall Street, and horse breeding and racing. He and his wife became regulars at the nation's race courses such as Saratoga in New York. Their Air Chute won the Premier Handicap at Hollywood Park in 1938, and Slide Rule took third in the 1943 Kentucky Derby.

In 1909, Boeing was accepted by other owners to become a resident of The Highlands, an exclusive enclave three miles north of Seattle on Puget Sound and limited to 100 families. The Brookline, Massachusetts, landscape architecture firm of the Olmsted Brothers designed the streets and parks. Boeing bought 16 acres on Boeing Creek where in 1913 he built a mansion designed by Seattle architect Charles Bebb. Boeing occupied the home by himself until 1921 when he married Bertha Potter Paschall. The newlyweds were joined by Bertha’s sons, Nathaniel Jr. and Cranston. Their son, William E. Boeing Jr. was born in 1923.

Boeing enjoyed horse racing, golf, fishing, and boating. In 1930, he commissioned construction of the 125-foot Taconite (after the iron ore that helped build the family fortune) and he cruised Northwest and Canadian waters. A Douglas float plane ferried mail to the company executive. It was on one of these vacations that Boeing met bush pilot Clayton Scott at the fuel dock in Carter Bay, British Columbia. Boeing hired Scott to pilot the Douglas amphibian around the country. On their way back from the east coast bucking headwinds in 1938, Scott suggested that the seaplane was not really appropriate for transcontinental executive flying. Boeing said, "When we get to Los Angeles, why don't you look around for another airplane" (Tacoma News Tribune, June 6, 1997). The result was the purchase of a demo model of Douglas's new twin-engine DC-5.

Boeing supported charitable organizations, one of which was Children's Orthopedic Hospital in Seattle. During the Great Depression, more than 90 percent of the care Children's delivered was free, which left the hospital in the red. Each of those years, a committee of the women trustees went to Boeing, who wrote a personal check for the deficit -- on the condition that his involvement remained anonymous. His contributions were not revealed until more than 50 years after his death by which time Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center had become one of the top pediatric institutions in the nation.

In 1942, the Boeings bought property northwest of Fall City, Washington, where they built the 650-acre Aldarra Farm to breed horses. He donated his Highlands home to Children's Orthopedic Hospital in 1950. The Orthopedic sold the property to broadcasting entrepreneur Elroy McCaw. Both Boeing stepsons entered the aircraft manufacturing business and his son went into real estate. In 1947, Washington State College at Pullman awarded Boeing an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws.

Conrad Westervelt never profited from his work with Boeing, but he continued to advance aviation in his Naval career. During World War I he supervised all Navy construction of aircraft. In 1919, he designed the NC-4 flying boat which became the first airplane to cross the Atlantic. Westervelt retired from the Navy as a captain and worked in aviation up to and through World War II. He died in Florida in 1956. William Boeing died of a heart attack aboard the Taconite on September 28, 1956, after a long period of failing health, just three days before his 75th birthday. According to his son, Boeing "pursued his curiosity, studied things carefully, and never dismissed the novel" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer).