On June 30, 1930, by a vote of six to two, the Seattle City Council approves an ordinance extending Aurora Avenue through Woodland Park. The Council majority follows the advice of city and state highway engineers, supported by Mayor Frank E. Edwards, that the multi-lane Aurora "speedway" is needed to provide a direct approach from the George Washington Memorial (Aurora Avenue) Bridge then under construction to north Seattle and beyond. The council decision to bisect Woodland Park's 200-acre urban wilderness triggers outrage among park supporters and other speedway opponents. With the vociferous backing of

The Seattle Times

, opponents gather sufficient signatures to force a referendum on the council decision, but voters in the November election approve the ordinance and two years later the speedway is built through the park.

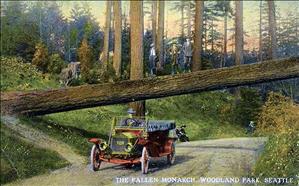

Woodland Park

Woodland Park originated as the estate of developer Guy C. Phinney (1852-1893) and his wife Nellie (Wright) Phinney (d. 1909). Nellie Phinney was unable to maintain the estate after her husband's death, and offered it to the City of Seattle for $100,000. Overriding a veto by Mayor Thomas J. Humes (d. 1905), the City Council approved the purchase in late 1899. Several years later, John C. Olmsted of the Olmsted Brothers landscape architecture firm incorporated Woodland Park into his 1903 master plan for the Seattle Parks System. Olmsted's design included a proposal for a permanent "Zoological Garden," expanding on the small menagerie that the Phinneys had maintained on the estate.

The Woodland Park zoo opened in 1904, and additional facilities were added to the zoo and park over the years. By 1930, the Times asserted that Woodland Park "has been the city's greatest park area for more than thirty years" ("Woodland Park Cost $100,000 ..."). But unlike other large parks, Woodland Park lay directly on logical transportation routes, located as it was between the Fremont neighborhood and downtown Seattle to the south and Greenwood-Phinney and other growing neighborhoods in north Seattle and beyond. As early as 1907, the King County Good Roads Club tentatively suggested a "driveway" through the park, but evidently backed off in the face of strong community opposition, exemplified by a front page editorial in The Interlaken that asked, "Shall Woodland Park be Disfigured?" and warned that Seattle would be a laughingstock for making parks into commercial centers.

Plans for a road through the park resurfaced a generation later, and the controversy came to a head in 1930, with construction already under way on the Aurora Avenue Bridge (whose official although rarely used name was the George Washington Memorial Bridge). Seattle politicians and business leaders had been pushing for a high bridge across Lake Union since the 1920s. At the time only four drawbridges -- Ballard, Fremont, University and Montlake -- connected the north and central/southern sections of the city. The middle two -- Fremont and University -- were well over capacity and heavily congested.

The Bridge Approaches

The state Highway Department and "good roads" groups also wanted a new bridge to carry through traffic on Pacific Highway (later Highway 99), then the state's primary north-south route, more efficiently through Seattle. Governor Roland H. Hartley (1864-1952) and the state Legislature agreed to pay $1 million toward the project if Seattle and King County each contributed a similar amount, which they did. The city and state also split responsibility for the project, with the state designing and building the bridge itself, while the city was to locate and construct the bridge approaches. This placed the controversy over the park route squarely in the city's lap.

Numerous routes for a high bridge over Lake Union were proposed, with possible crossings at Stone Way, Albion Place, Whitman Avenue, or Linden Avenue considered in addition to Aurora. Director of Highways Samuel J. Humes (1883-1941) (coincidentally, the son of Mayor Humes who had tried unsuccessfully to veto the city's acquisition of Woodland Park) chose the Aurora route in 1928 and excavations for the bridge piers began in 1929.

Although a highway extending straight from the north end of the bridge would necessarily cross Woodland Park, the Highway Department's choice of the bridge location did not include an official decision to bisect the park. Since the route beyond the bridge was considered to be the "approach," the decision was officially up to the city. Nevertheless, Hartley and Humes made clear that they preferred the straight route through the park favored by both state and city highway engineers.

The Seattle Times and other park supporters bitterly denounced the engineers' plans to "sacrifice" the park in the name of automotive efficiency. They argued that the speedway through the park would save drivers only 25-30 seconds and that existing roads (West Greenlake Way east of the park and Fremont Avenue to the west) were adequate for all the traffic crossing the bridge.

The Road Goes Through

Opponents of the speedway thought they had prevailed in mid-June 1930, when Mayor Frank Edwards said he opposed a "thoroughfare" through Woodland Park and the City Council directed the city engineering department to prepare an ordinance that would have extended Aurora Avenue only to 39th Street, south of the park. That may explain the fury with which speedway opponents reacted when the mayor and council majority changed course. By the end of the month, Mayor Edwards was agreeing with city engineers that the road should go through the park, and on June 30, 1930, six councilmembers voted in favor of the ordinance adopting that route, with only George W. Hill and council president Oliver T. Erickson opposed.

The Seattle Times responded with outraged front-page headlines, including "Sacrifice of Park Is Voted," "Friends of Playfields Deceived in Aurora Act," and even "Nero Was a Piker." The newspaper repeated its denunciations when Edwards signed the ordinance into law on July 10, 1930, and promised a referendum campaign to overturn the ordinance. Speedway opponents gathered enough signatures to place the referendum on the November 4, 1930, ballot. However, despite the efforts of the Times, voters approved the speedway ordinance by a substantial margin, with more than 37,000 in favor and around 29,000 opposed.

Speedway opponents brought several court cases challenging the county and city bonds issued to fund the bridge and approaches and the city tax assessments imposed on property near the bridge deemed to be "specially benefited" by the project, but all the challenges were rejected. However, as a result of the controversy over the speedway route, the referendum, and the time needed to condemn property along the route, construction of Aurora Avenue through Woodland Park did not even begin until months after the Aurora Bridge itself opened in February 1932.