James J. Hill, nicknamed the Empire Builder, embodied the archetypal American story of success, rising from poor dock clerk to multimillionaire railroad magnate. In time, Hill had gained control of the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and the Burlington railroads. James J. Hill was perhaps more significant to the framing of the empire of the Pacific Northwest than any other individual. His decisions about rail routes and station stops had the power to turn fledging communities into robust cities -- and to cause other hopeful towns to die a bornin'. Settlers cultivated land along the margins of the tracks he laid, later shipping the products of their farms to distant markets via the trains. Hill's impact on the economic development of the Midwestern and Pacific Northwestern regions of the United States is difficult to overstate.

Early Years

James Hill was born in his family's log house in Rockwood, County of Wellington, Upper Canada (later Ontario) on September 16, 1838. He was the third child of four born to Anne Dunbar Hill and James Hill, a successful farmer who later owned a tavern. A childhood accident with a bow and arrow left Hill blind in the right eye, a disability that was not readily apparent and seems to have hindered him little if any. William Wetherald, a Quaker who directed the Rockwood Academy in nearby Guelph where Hill was enrolled from about age 10, was a particularly strong influence to Hill's intellectual development. In later years Hill remembered having read voraciously in his youth. At age 13 he adopted the middle name Jerome after Napoleon's brother.

His father died the following year. As the eldest surviving son, James was compelled to leave school and find work clerking in various small stores in order to support his mother, sister, and younger brother. Four years later when his younger brother was old enough to take his place as head of the family, James Hill left home. He paused in Syracuse, New York, to earn money as a farm laborer, then traveled on to New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, and eventually by steamer down the Mississippi to St. Paul, Minnesota Territory, then a rough but promising community centered on Mississippi river commerce.

Hill quickly found work as a clerk on the St. Paul levee, clerking for J. W. Bass & Company, agents for Dubuque & St. Paul Packet Company's river steamship company. The goods that arrived at St. Paul on the Mississippi continued on to their final destinations via ox cart -- inefficient, but at the time the only option.

Marrying Mary

In 1864 Hill married Mary Theresa Mehegan (1846-1922), a waitress at the Merchant's Hotel dining room where Hill took many of his meals. The daughter of Irish immigrants and a devout Catholic, Mary Mehegan spent some time during her courtship with Hill attending St. Mary's Institute, a finishing school for genteel young ladies run by the Sisters of Notre Dame. There Mary gained skills that no doubt stood her in good stead as her ambitious husband grew in wealth and power. Their 10 children were Mary, James, Lewis, Clara, Katherine (who died in infancy), Charlotte, Ruth, Rachel, Gertrude, and Walter.

(NOTE: On September 6, 1888, James and Mary's eldest daughter, Mary, wed Samuel Hill (no relation), making her Mary Frances Hill Hill. Sam Hill named his model community on the banks of the Columbia River Maryhill after his wife and their daughter, Mary Mendenhall Hill.)

Hill's Business Foothills

In 1869 Hill resigned his clerkship and ventured into business on his own, forming Hill, Griggs, and Company in partnership with Chauncey W. Griggs. They warehoused and shipped coal, lime, cement, and salt on the Mississippi and Red rivers. America was becoming increasingly coal-dependent during the 1860s and 1870s, and Hill worked to build up St. Paul's coal industry, learning everything he could about the fuel. Through Hill's encouragement, the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad and later the Milwaukee Railroad made the switch from wood to coal. The profit Hill made from selling coal funded his next business venture: railroads.

After nearly a year spent arranging financial backing and in partnership with George Stephen, Donald Smith, and Norman Kittson, James J. Hill purchased the financially troubled St. Paul & Pacific Railroad in 1878, reorganizing the line under the name St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba Railway Company. Under Hill's guidance (first as general manager and after 1883 as president), the company constructed track to St. Vincent on the Canadian border -- and then turned its attention toward the West. A brief entanglement with the Canadian Pacific Railway ended badly, and when Hill began the push toward the Pacific Ocean, it was on the United States side of the border.

The Hills at Home

In 1871 the Hills moved to a modest cottage at Ninth and Canada in St. Paul. In 1876 Hill had the cottage torn down and replaced with a very modern (for the time) three-story Second-Empire style home. After 1883 the family also maintained a country home and experimental farm in North Oaks, Minnesota. Hill experimented with various crops, farming techniques, and livestock breeds, later passing this knowledge on to the settlers establishing farms along his railroad lines.

In October 1880, Hill renounced his allegiance to the country of his birth and became a United States citizen.

In 1891 James and Mary Hill and their younger children moved into their recently competed 32-room, 36,000-square-foot, red-sandstone mansion at 240 Summit Avenue in St. Paul. Perched on a high bluff overlooking downtown St. Paul and the Mississippi River, the home was designed by the Boston firm Peabody, Stearns, and Furber to James Hill's exacting specifications. Summit Avenue was (and is) a four-and-one-half-mile boulevard of mansions, churches, and schools. At the time the Hills built their home, Summit Avenue was the expected home address for Minnesota's business elite. Their home was (and is) the largest house on Summit Avenue. In 1902 the Hills' eldest son, Louis W. Hill, and his wife, Maud Taylor Hill, began construction of their own mansion next door.

The Great Northern Railway

In 1889 the St. Paul & Pacific was renamed the Great Northern Railway. Hill pushed the line toward the Pacific coast, using the 5,214-foot Marias Pass to cross the northern Rocky Mountains and a circuitous series of switchbacks over Stevens Pass to cross the Cascades. (The Cascade Tunnel replaced these switchbacks in 1900. It was then replaced by the lower-elevation New Cascade Tunnel in 1929.) Through 1892 the line pushed steadily across Washington, arriving at tidewater in Everett before heading south. The line reached its terminus in Seattle on January 7, 1893, narrowly avoiding construction delays that might well have resulted during the subsequent worldwide financial panic of 1893. During 1893 the Northern Pacific Railroad (the rival railroad to the Great Northern in the Pacific Northwest), the Union Pacific, and the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe all went bankrupt, leaving the Great Northern the only solvent transcontinental line.

The Northern Pacific Railroad charged $60 for tickets in first class and $35 for second-class tickets from Seattle to St. Paul. Hill undercut this rate significantly, setting the Great Northern prices at $35 for first class and $25 for second. Freight charges on timber, Washington's most significant product, also significantly undercut the competition: Hill charged 50 cents per hundred pounds of cedar and 40 cents per hundred pounds of fir, compared with 90 cents per hundred pounds charged by the Northern Pacific. Hill biographer Michael P. Malone states: "These rates opened a booming market for Northwest lumber all the way to the eastern seaboard and the South, but most particularly the Upper Midwest, and the shipments increased yearly throughout the decade" (p. 153).

Hill frequently compared the Great Northern western terminus in Seattle to the head of a rake. The long transcontinental line was the rake's handle, and the tines extended from Seattle to Portland, Tacoma, Everett, Bellingham, and Vancouver, B.C. According to Malone, this rake "would sweep in the bounty of the region" (p. 141). Hill accomplished some of this rake-making by acquiring smaller local railroads in the region and folding them into the Great Northern Railway.

He built the Great Northern without the advantage of massive governmental land grants that had helped funded construction of the Northern Pacific line. The New York Times later reflected that "skeptics regarded his plans as impossible of successful completion, and the extension [from Minnesota to Puget Sound] became known as 'Hill's Folly' ... . Critics said that he was building through a country barren of people, which could give his line no tonnage and would mean ruin. But they reckoned without the genius of the empire builder. He laid rails westward at the rate of a mile a day, and at an average cost of $30,000 a mile, and as he went he left a trail of embryonic farms and homesteads by the railside. Thus was the foundation laid for the coming empire" ("The Career of James J. Hill," May 30, 1916).

The Empire Builder paid himself no salary from his railroad. His gains came from the Great Northern stock he held.

Cattle, Hogs, and Wheat

Once the main Great Northern line was complete, he began the process of building an empire around it, making the land produce so that his railroad could transport its products to market. He introduced beef cattle and hogs to the bunchgrass prairies his rails snaked through and encouraged ranchers to use scientific breeding procedures to improve the herds. He ran demonstration trains to nascent wheat farming communities across the West. Farmers could take advantage of onboard experts who taught methods of extracting the maximum amount of wheat per acre. As grain crops began rolling in, Hill reduced freight charges so the farmers could efficiently ship their yield to market.

Like the Northern Pacific, the Great Northern promoted the territory along its rails to emigrants through promotional materials. Trains carried hopeful emigrants in, and in due time carried wheat, cattle, and other farm products out. Hill encouraged farmers to utilize scientific methods to raise their crops.

A Passion for Railroad Domain

As The New York Times gracefully put it in a posthumous article summing up Hill's accomplishments, "Mr. Hill's great passion for empire building conflicted with another great passion for railroad domain, and there ensued a great stock market fight for control of the Northern Pacific" ("The Career Of James J. Hill," May 30, 1916). Hill's convoluted grab for controlling stock in the Northern Pacific included both the creation of a panic on the New York Stock Exchange and the intervention of the United States Supreme Court, but ultimately succeeded. This gave him control of both transcontinental lines into the state of Washington.

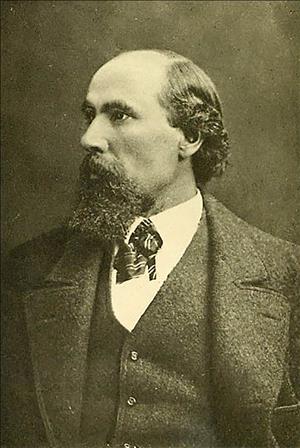

The same article offered an associate's description of Hill during this period: "Somewhat below the average height, but built like a buffalo, with a prodigious chest and neck and head; his arms long, sinewy, powerful; his feet large and firm planted and his legs solid as steel columns -- truly a massive imposing figure of a man. And the head -- shaggy brows, shading an eye that bored right through; a mass of long iron-gray hair reaching to the collar of his coat; and a heavy, rough, iron-gray beard growing without restraint over the entire face, yet hiding nothing of the immense chin and powerful jaws, and the wide lips, between which showed two rows of teeth seemingly fit to crunch iron."

In 1901 Hill added the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad to his collection.

On September 6, 1901, Hill merged the Great Northern, Burlington, and Northern Pacific Railroads into the Northern Securities Company, much to the consternation of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919). In 1902 the federal government filed suit against the Northern Securities Company. On March 14, 1904, the United States Supreme Court decreed that the Northern Securities Company be dissolved, citing the Sherman Anti-Trust law of 1890.

Hill's final act of railroad expansion was the construction of the Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Railroad. The line ran along the north bank of the Columbia River gorge. It was completed in 1908.

Hill's railroads were built (or sometimes re-built, as was the case with some sections of Northern Pacific track) upon three principles: low grades to ease the work of hauling, heavy locomotive power, and freight cars with large capacity. Hill rode the rail line frequently in his private railcar, the Manitoba, managing mainly by direct oversight rather than by delegating. He had a reputation as a taskmaster with a temper. Hill biographer Michael P. Malone called him "a legend in his own time, an ogre to many, a force larger than life to nearly all" (p. 159).

Northwest Timber

Along with the Northern Pacific, Hill got what remained of the massive (68,750 square miles) federal land grant the Northern Pacific had received in the 1870s and early 1880s as an incentive to build. On January 3, 1900, Hill signed a contract transferring this land to timber industry leader Frederick Weyerhaeuser for $6 per acre. Weyerhaeuser and Hill were Summit Avenue neighbors. The deal was exceedingly good for Weyerhaeuser: When the purchase was fully inventoried it became clear that he had paid only 10 cents per 1,000 board feet. This sale jump-started the modern timber industry in the Pacific Northwest.

Hill gave Weyerhaeuser an extremely low shipping rate for timber and thereafter Great Northern cars headed east laden with old growth timber. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer quoted historian Clarence Bagley: "In a twinkling, the value of Washington timber holdings had increased by an amount as great as the capital stock of the Great Northern Railway Company" ("Record Shows Seattle's Great Debt To J. J. Hill," May 30, 1916).

In 1900, Hill formed the Great Northern Steamship Company to ship goods between Seattle and Yokohama and Hong Kong. Two vessels, the Minnesota and the Dakota, carried this freight. Although the venture lost money, Hill was among the earliest to foresee the eventual development of an economy that linked the Pacific Northwest with Asian Pacific Rim countries.

In 1906 Hill opened King Street Station in Seattle. King Street Station served both the Northern Pacific and the Great Northern railroads and offered rail passengers a gracious entry into the city.

In 1907 Louis Hill succeeded his father as president of the Great Northern Railway. James J. Hill remained chairman of the board, retiring from that position in 1912. Again, his son Louis succeeded him. Louis Hill was instrumental in the branding and marketing of the Great Northern. Under Louis Hill's watch the Great Northern adopted the iconic mountain goat logo and the slogan "See America First" and contributed significantly to the development and promotion of Montana's Glacier National Park.

Golden Years

Only three years after retiring from railroad business, James J. Hill bought the First National and Second National banks of St. Paul. He reorganized them as the First National Bank of St. Paul. In 1910 he published Highways of Progress, a treatise on farm methods, trade, and the nation's future. He spoke frequently at fairs and gatherings throughout his Empire, including delivering the keynote speech at the opening ceremonies of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle on June 1, 1909. Hill told the crowd, estimated to have been as many as 90,000 people, "This exposition may be regarded as the laying of the last rail, the driving of the last spike, in unity of mind between the Pacific coast and the country east of the mountains" ("James J. Hill Says Exposition Makes Unique Appeal," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 2, 1909).

Hill made what turned out to be his final trip over the transcontinental line in late May 1914.

The Empire Builder's Demise

James J. Hill died on May 29, 1916, at the age of 77. The New York Times stated that the cause of death was "a hemorrhoidal infection, which dates from May 17" (J. J. Hill Dead In St. Paul Home ... ," May 30, 1916, p. 1). The Seattle Post-Intelligencer described the cause of death as infection stemming from as "a carbuncle on the posterior of his thigh, which has resulted from bowel trouble" ("Hill Rallies Quickly After Knife Is Used," May 28, 1916, p.1). Although Hill's physicians drained the abscess, his temperature began to climb and gangrene to spread. The United Press reported that "newspapermen, motion picture operators, and press cameramen began besieging the Hill mansion ... special trains began bringing friends and relatives to the bedside ... Father Thomas J. Gibbons, pastor of the St. Paul Cathedral and vicar general of the St. Paul archdiocese, hastened to the bedside" (The Tacoma Tribune, May 29, 1916, p. 1). The St. Paul Cathedral, in use for services but still under construction at the time of Hill's death, is located about a block away from the James J. Hill mansion. Most of Hill's immediate family was present when he died.

Hill's funeral was held in the drawing room of his St. Paul mansion. Pallbearers ranged from Hill's private secretary M. R. Brown to high-ranking officials in the Great Northern Railway to Charles Maitland, whom The New York Times described as "for twenty-five years a coachman in the Hill family ("J. J. Hill Dead In St. Paul Home ...," May 30, 1916). Flags in Minnesota flew at half mast, public school in St. Paul was cancelled for the day, and The New York Times reported, "Every wheel on the three great railroad systems he controlled stopped turning for five minutes at 2 o'clock this afternoon. All trains halted, and the steamships in the Great Northern Pacific service along the western coast likewise hove to" ("James J. Hill is Buried").

The Most Effective Friend

In Washington, a state whose destiny had been so greatly shaped by James J. Hill, citizens both prominent and ordinary memorialized his contributions. "No man of his day had the capacity to size up the character and resources of a new country like Mr. Hill," the Seattle Post-Intelligencer quoted Seattle Chamber of Commerce president and well-respected civic leader Judge Thomas Burke. "Up to the time of the building of his railway to the Puget sound the markets of the Middle West were closed to our lumber because the freight rates were too high. Mr. Hill of his own motion cut the lumber rates in two. This great industry instantly sprang into life. The woods were filled with men, and the Puget sound country entered upon a career of prosperity that the most hopeful had never dreamed of ... He was far and away the most influential and effective friend Seattle ever had" ("Hill's Success Attributed To His Foresight," May 30, 1916, p. 5). Thomas Burke had been Hill's attorney in the Pacific Northwest for many years.

Tacoma resident E. G. Griggs, whose father had been Hill's earliest business partner in St. Paul, told the Tacoma Daily News, "He had the reputation of being an exacting man and hard to get along with, but at the same time it was recognized these qualities made him the forceful man he was, a man brilliant in large achievements" ("George T. Reid Explodes Old Story of Hill's Vow," May 29, 1916, p. 11).

Mary Hill died in 1922 and was buried next to her husband near Pleasant Lake on the North Oaks farm. Both graves were later moved to Resurrection Cemetery in St. Paul. In 1925, four Hill daughters donated the Summit Avenue mansion to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. Paul. In 1961 it was designated a National Historic Landmark. In 1978 the Minnesota Historical Society acquired the James J. Hill mansion, restored it, and opened it to the general public.