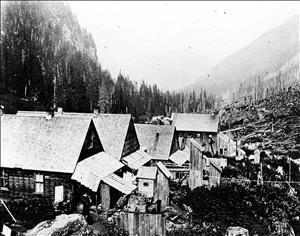

On November 16, 1897, Chinook rains causing heavy flooding begin the process of destroying access to the Snohomish County mining town Monte Cristo. The flooding event, known as "The Deluge" or "the Washout," will destroy railroad access to this isolated Cascade Mountain town. John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) owns the railroad and he will decline to rebuild. The gold and silver "hard rock" mines, unable to ship their ores, will be forced into bankruptcy. Rockefeller will take over the mines, but they will not reopen until 1900, by which time many workers and their families will have moved on. "The Washout" abruptly ends the mining boom in Monte Cristo.

Floods Following Floods

Although November and December floods are nothing new in the Cascade Mountains, they seldom happen in consecutive years. But in 1896, the year before "The Washout," not one but two flooding incidents occurred.

The first, in early November 1896, caused some 150 miners to walk out for an expected two weeks until the railroad was repaired, leaving enough supplies for mine caretakers and women and children. Then a second storm blew in, wrecking the construction gangs’ work, and disrupting the schedule. Residents took it in stride and the mines reopened in mid-January. During the second flood, a baby was born on an Everett & Monte Cristo Railway push car. Dr. Miles and his wife had already evacuated and nurses worried about the mother’s condition, but the baby entered the world without complication.

The next year, on November 16, 1897, warm and heavy Chinook or "Pineapple Express" rains began pouring onto steep slopes covered with early snowfall. Residents’ initial reaction was surprise, then fear as heavy rainfall increased even more than the year before, turning into what some, such as the Breazeale family, called "The Washout" and others called "The Deluge." Either term applied: This was the greatest flooding event county residents ever had seen.

Churning Torrents

The warm subtropical rains poured down, filling streams and rivers to churning torrents of mud, trees, and railroad and townsite structures. The sound and smells were unforgettable. Massive stones moved along river bottoms, rumbling as they shifted channels. On the South Fork Sauk River, erosion cut away banks from one side of the narrow valley to the other, flowing around obstructions and throwing up piles of woody debris atop new gravel bars. Along the South Fork Stillaguamish, tracks, trestles, bridges, and bridge approaches disappeared downstream. Through Robe Canyon the rail line simply was gone, save for debris-packed tunnels.

Downstream from Monte Cristo, along the Sauk River, much of the original wagon road washed away. This was the original route up the Sauk River from the Skagit, essentially the location of today's Mountain Loop Highway, especially from Bedal up to Barlow Pass.

Eleven miles downstream from Monte Cristo, at the confluence of the North and South Forks Sauk River, the river cut a new channel through the fields of the Morehouse homestead, destroying their buildings. The Morehouse homestead had the Orient Post Office. The residents fled to the nearby Bedal family cabin, where a canoe was kept tied to the front porch in case of need. Ultimately the Morehouse family left the area and the Bedal family took over the post office and raised their family on the site.

Down at the mouth of the river, the community of Sauk City was destroyed, never to be rebuilt.

From the mines and town, refugees from Monte Cristo again headed down toward Silverton and Granite Falls, carrying what they could. Hilma Johnson, then 4 years old, recalled being carried on the back of one "Black Nels." Edna Breazeale’s earliest memory was of finding shelter at Silverton where she, her parents, and her two older brothers straggled in after dark. Their place out of the rain was a stable, the owner’s wife taking pity on the bedraggled family and asking her husband to make room somewhere in their already-jammed home. The woman was wearing a black dress and white apron. Edna’s mother later explained to her why that image remained imprinted in her barely 2-year-old mind.

Rockefeller's Move

With no organized charity to aid those who had lost their homes, jobs, and belongings, the people who had lived in the mining town made do and awaited expected repairs to the railroad. This would allow a resumption of work.

Those hopes were dashed when Frederick T. Gates (1853-1929), acting on behalf of John D. Rockefeller, used the situation to his employer’s advantage. He kept the railway closed, thus forcing the mining companies into bankruptcy. Then he took them over. By the time he rebuilt in the early summer of 1900, it was far too late for the residents of 1897.

Monte Cristo's Working Families

Some of Monte Cristo's men left for the Klondike gold fields or for Mexican silver mines. Some headed for Seattle and others went to Snohomish County logging camps looking for work.

John H. Breazeale (1865-1947) was one of the latter, finding a job in Machias on a railroad section crew and then as a logging camp timekeeper. Later he walked back to the abandoned town to pack out blankets and quilts. Everything else the family owned was gone. They moved to British Columbia, where he again supervised a concentrator as he had done before the flood. In 1907 the Breazeales returned to Monte Cristo to work for mining speculator Sam Silverman’s (b. 1859) effort to reopen the mines, but that too ended shortly, due to a lack of financing.

When the second period of mining began, in 1900, it was a quieter and less productive time. The boom years had ended abruptly with that November storm, abetted substantially by financial maneuverings over which the people of the community also had no control.