In the decade of the 1890s, Monte Cristo became the center of a mining boom. It attracted thousands of miners, businessmen, laborers and settlers into the rugged Cascade Mountains of eastern Snohomish County, yet its fate would be determined not by their efforts but by the difficult climate, unknown geology, and decisions made by financiers a continent away. Today the isolated area still is a popular site for visitors attracted by its history and dramatic setting.

The Early Mining Years

Since the 1870s, small-scale attempts at gold and silver mining had been made in the Silver Creek district of southeastern Snohomish County. This narrow valley runs north and then east from the North Fork Skykomish River 11 miles upstream from the town of Index. Difficult trail access and little local investment money restricted any real development. This changed in 1889 with the discovery of gold and silver bearing ores at the then-unknown nearby headwaters of the South Fork Sauk River.

Joseph L. Pearsall made that initial find, sharing the information with Frank Peabody, who in turn made contact with John MacDonald Wilmans, an experienced mining man visiting Seattle on business. Upon further investigation, Wilmans backed the location of lode claims along the main vein, which visibly extended from 76 Gulch through Wilmans Peak and into Foggy Peak to the north. Involving his brothers Frederick and Steve, with additional backing from Thomas Ewing and George W. Grayson, followed by Judge Edward Blewett, Hiram G. Bond of New York City, and Seattle publisher Leigh S. J. Hunt, the Wilmans group spent the following two seasons improving the trail over the steep ridge from Silver Creek, defining ore bodies, and starting construction of a wagon road down the length of the Sauk River to its confluence with the Skagit River as a way to bring in required machinery.

Recognizing that the only way to move the anticipated massive tonnages of ore and concentrates would be by rail, they also hired skilled engineer John Q. Barlow to survey a railroad route to parallel their road. Four miles below Monte Cristo, Barlow discovered the pass named for him and realized that it led to the South Fork Stillaguamish River valley and a possible link to the newly announced heavy manufacturing city of Everett directly to the west on Port Gardner Bay. According to reports, this was being developed by Tacoma lumberman Henry Hewitt in partnership with Charles L. Colby (1839-1896) and Colgate Hoyt (1849-1922) of Colby, Hoyt & Company of New York City, with major funding from the country’s richest man, John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937), creator of the Standard Oil Company monopoly.

With an offer of mining shares and a guarantee of exclusive shipping if the Everett syndicate built a railroad to Monte Cristo, the Wilmanses traveled east in 1891. After a positive mineral inspection by mining expert Alton Dickerman, the New Yorkers not only accepted the offer but bought a controlling two-thirds interest in the best properties and more stock the following year. The Monte Cristo, Pride of the Mountains, and Rainy mining companies were created, along with the United Concentration Company to erect a plant to process the ore into concentrates to reduce shipping costs. The Wilmans brothers retained their holdings on Wilmans Peak and organized the Golden Cord and Wilmans mining companies.

Smelter, Railroad, and Labor

Adding mines to the original plans for Everett meant creation of a smelter to turn the concentrates into bullion. Thus the Puget Sound Reduction Company was created. Linking the parts, the syndicate formed the Everett & Monte Cristo Railway Company, purchasing the partially constructed Snohomish, Skykomish, and Spokane Railway (called the "3 S" ) line between Snohomish and Lowell, and then constructing their own grade from Hartford Junction near Lake Stevens to Monte Cristo via Granite Falls, Robe Canyon on the South Fork Stillaguamish River and the mines at Silverton. After weather and flood delays, the line finally reached its destination in September 1893. Between Snohomish and Hartford, the company leased trackage rights from the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway.

Attracted by news of Rockefeller money backing the gold and silver strike at Monte Cristo, thousands of people flocked into the area seeking their own claims, while others took up homesteads in the lower valleys, cut timber, built shingle and saw mills, and established support businesses. Thousands more were needed as construction labor on the railroads (the Great Northern Railway was completed from St. Paul, Minnesota to Everett and then Seattle in 1893) and hundreds in the mines.

This stimulus helped propel Everett into overwhelming dominance over the rest of Snohomish County. Yet at the same time the national economy was falling into severe depression, the Panic of 1893. This crisis lasted until the 1897 Klondike gold rush. With banks failing, demand for goods collapsing, and credit markets drying up, the Everett syndicate found itself unable to raise enough funds to keep its projects alive.

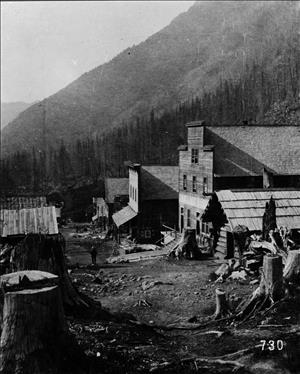

In Monte Cristo two separate townsite plats were filed in the spring of 1893. These and a shortage of level land led to the creation of upper and lower towns, separated by the railroad yards in the flat near the junction of Glacier and 76 creeks. Dumas Street formed the backbone of the upper neighborhood, with commercial businesses, mining infrastructure, the school, a church, the post office, and view property. Below the tracks were more saloons, railroad and worker housing, social halls, and additional businesses. Among those was the real-estate office of Frederick Trump, grandfather of future U.S. President Donald Trump.

Reorganization and Production

It was not until 1894 that the mining infrastructure was ready to start regular shipments to the smelter. By then the Everett corporations were bankrupt and could not meet their bond obligations. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Rockefeller sent out his trusted advisor, Frederick T. Gates, to investigate and restore financial order. Over the next several years Gates completely reorganized the companies involved, forcing out Hewitt, Colby and Hoyt in favor of loyal Rockefeller men.

From 1895 to 1897 production grew steadily from the mines, primarily the Pride of the Mountains, Pride of the Woods, and Mystery adits (mine entrances) on Mystery Hill through lower Glacier Basin and into the slope of Foggy Peak. Ore was shipped via aerial tramways a half-mile from the Mystery and a mile from the Pride of the Mountains to the terminal bunker a quarter of a mile above the concentrator. Here it was crushed (safely away from the vulnerable milling machinery), then hauled along a covered ground tramway to the top level of the five-story concentrator building. After further crushing and screening, the valuable concentrates were loaded onto Everett & Monte Cristo boxcars for shipment down to the Everett smelter.

Additional ore came from the O&B, developed by Snohomish Eye newspaper publisher Clayton H. Packard, and the Wilmans brothers’ Golden Cord. Located on Toad Mountain west of the townsite, the O&B frequently was in financial straits, which limited its sporadic production. Wilmans ore concentrated poorly, while its main source was the Comet mine, located almost inaccessibly high above the town on Wilmans Peak. The brothers also had other business affairs, which typically kept them away from Monte Cristo and dependent upon finding trustworthy contractors. Both companies utilized aerial tramways and terminal bunkers near the town.

Difficulties

Poor working conditions and substandard pay led to labor unrest in 1895. However losses from initial owner concessions were regained the next year with the imposition of longer shifts and higher boarding costs. Individuals deemed troublesome were replaced, often with Cornish and other immigrants from Rockefeller companies in Michigan. Facing nationwide depression, miners had little bargaining power.

A greater limiting factor for profits was severe Cascade Mountain weather. Beginning annually in November, moisture-filled storms blew in off the Pacific Ocean, dumping feet of rain as clouds encountered the range and rose over it. Early wet snowfalls melted with the higher temperatures and downpours, the combination periodically causing rivers in the narrow canyons to rise swiftly and destroy railroad grades, inundate lower-lying ground, and isolate communities until repairs could be made. On the steep peaks above town avalanches let go, sweeping away tramway towers and occasionally men caught in their paths.

As a result, mine superintendents were forced to reduce sharply their winter operations, resuming again after damage repair in late spring. Keeping the railroad open cost far more than anticipated, aggravated by the syndicate’s decision to locate the grade too close to the river through Robe Canyon. This necessitated construction of six vulnerable tunnels (an uncompleted seventh, upstream from Gold Basin, collapsed during boring), and placed the tracks well within range of flood waters. Tunnels were damaged in 1892, twice in 1896, and disastrously in 1897.

Quality and quantity of ore were the key issues. Unlike deposits in the Rocky Mountains with which the nineteenth-century miners were familiar, those of the Cascades were far younger and the product of ongoing volcanic action of tectonic plates. Thus they assayed well from surface outcrops as Pearsall had seen, but unexpectedly lost quality and dwindled rather than growing richer. The original Independence of 1776 claim quickly was worked out, for example, and in 1896 the deteriorating Pride of the Mountains received new life only when its New Discovery vein was located beneath the original adit. Arsenic was an additional cost, its presence in the ore causing the smelter to levy penalties until 1898, when the company installed a plant to process it.

The Long Shutdown

In November 1897, the worst flood known to date caused massive damage to the railroad, lower townsite, and downstream settlements. With no hope for fresh supplies, Monte Cristo was abandoned, its residents walking down the damaged tracks and remaining bridges to Granite Falls, carrying what they could and asking for shelter. Few returned. Frederick T. Gates took advantage of the disaster, rejecting needed railroad repairs until miners and businessmen agreed to sharply higher freight rates. When they balked, he kept access closed and forced them into bankruptcy. As a result, he gained total control of the major mines at Monte Cristo, forcing out minority stockholders.

In 1899 Gates sold off all of Rockefeller’s Everett holdings to Great Northern Railway president James J. Hill (1838-1916), save for the mining-related companies. Then the following year he began breaking up the railroad. The section from the smelter in north Everett to the city of Snohomish was sold to Hill’s rival, the Northern Pacific Railway, which also had acquired the former Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern. As a part of this deal he rebuilt the remaining Hartford-to-Monte Cristo section with Japanese contract labor crews and reorganized it under the name of the Monte Cristo Railway Company.

Mining: The Second Phase

Monte Cristo began its second and final existence as a mining district under the banner of the new Monte Cristo Company, Gates's newly consolidated structure. From the summer of 1900 until the autumn of 1903, steady production ensued, although in 1902 the Northern Pacific purchased the remainder of the railroad and turned it into the Monte Cristo Branch of the NP. That completed favorably, Gates arranged with the American Smelting and Refining Company, ASARCO, to unload the entire mining and processing operation. The Guggenheim-financed refining monopoly was not interested in ore extraction, but wanted the smelter, which it operated intermittently until 1912. It then was dismantled and much later became a hazardous-waste clean-up site in north Everett.

From then on until the winter of 1920 mining activity gradually sputtered to a close. A number of people attempted to revive production, notably the Wilmanses in late 1905-1906. They reorganized the Golden Cord into the Justice Mining Company and sold it to Sam Silverman. Unable to obtain adequate financing due to the Panic of 1907, he too had to shut down. A similar fate befell John F. Birney, who in 1914 tried to restore the Rainy mine across Glacier Creek from the old concentrator.

The Boston-American Mining Company was the last. After losing a legal battle over ownership of the O&B in 1909, it intermittently attempted to intercept that vein at an elevation just above the townsite from 1913 to 1920. Owners also considered reopening the Justice and tunneling into the Pride/Mystery workings. For that purpose they erected a new concentrator next to 76 Creek and a connecting aerial tramway. Investors put money in, but nothing of record was produced. After resuming following World War I, work ceased with a roar when an avalanche thundered down Toad Mountain at Christmas 1920, shattering both entrance and equipment for its exploratory mine near the base. Putting on packs and snowshoes, the last four miners walked out.

Recreation: A New Attraction

Since the early 1890s people had come to the Monte Cristo area for its scenic attractions, the mile-high mountain peaks surrounding the narrow valley with its glacial cirques, fish and wildlife, alpine Silver Lake and remote Twin Lakes. Letters home sent descriptions, the railroad ran excursions, and The Mountaineers completed a long summer climbing exploration in 1918 under the leadership of noted University of Washington professor Edmond Meany (1862-1935). Following the collapse of the Boston-American venture, one of its investors, John Andrews, moved from his Illinois home, picked up much of the abandoned real estate, and turned the surviving hotel into a resort. During the 1920s the Rucker brothers of Everett operated the railroad to serve their Big Four Inn near Silverton. Running gas-powered autos up to the town, it became a popular destination.

During the Depression and World War II years, however, business was lean or at a standstill, and Andrews sold out in 1951 to Del and Rosemary Wilkie. With the burst of postwar prosperity and automobile access via the new Mountain Loop Highway and connecting county road from Barlow Pass, the Wilkies put great effort into promoting their "ghost town" theme. With small cabins in the former railroad yards ( turned into a parking lot), a lunch counter and tiny museum in the resort/residence building (moved to the former Boston-American cookhouse), and cheap attractions such as "Slippery Sam" (a dummy lying in a board coffin), the seasonal business did well. On the other hand, many surviving artifacts were sold for scrap or antiques, the Boston-American ore bunker was dismantled for lumber, and mining claims were logged for their limited timber values.

In 1963 and again in 1967 the basic Andrews properties were sold to successive corporations whose members attempted with limited success to create a financially successful destination resort. The first purchasers were a group headed by Ken Schilaty. The second, called Monte Cristo Resorts, Inc., was led by Dr. Colby Parks and comprised men with ties to the University of Washington Medical Center. Both discovered that the surrounding slopes were unsuitable for skiing, snow conditions were heavy and wet rather than powdery, and the tourist season essentially lasted only from Memorial Day to Labor Day, ending sharply with the autumn rains. As with the mining railway, frequent damage to the county road also was an issue. Once again, the few remaining structures fell into decline with a lack of investment or maintenance.

The flooding cycles continued as well. On December 26, 1980, another severe event scoured the Cascades, cutting off the road half a mile above Barlow Pass and exposing a previously unknown huge clay slide. The road grade sloughed into the river below, and the South Fork Sauk River bridges stood isolated, their approaches gone. Above the Twin Bridges were washouts, debris flows, and scores of fallen trees. With that, the Snohomish County Council followed in the footsteps of Frederick T. Gates and decided to call it quits, declining to rebuild the road.

Revival Through Volunteer Efforts

On March 19, 1983, a driver reported to the Silverton sheriff’s radio operator that the Monte Cristo lodge was on fire. The man’s identification never was known, nor the cause of the blaze. With media reporting the "ghost town" vacant following destruction of the building, vandals made their way in and caused extensive damage to private and remaining resort properties.

Convened by David Cameron, a concerned group of property owners, hikers, climbers, those who loved the outdoors, and many with memories and ties to the old town, gathered a month later to form the Monte Cristo Preservation Association. After initial hesitation, then with the cooperation of county government, this private non-profit group restored limited access. They also influenced legislation creating the Henry M. Jackson Wilderness Area, which almost encircles and gives protection to the district. Through its volunteer efforts, the public continues to enjoy the spectacular setting of this historical region, including its ongoing road challenges.

In 1994 the association was successful in forming an alliance with the River Network and Trust for Public Lands for the latter to purchase the resort properties. Reimbursed by federal Land and Water Conservation Fund monies, the Trust turned over ownership to the U.S. Forest Service. Although hampered by continuing budget reductions, the agency and association have worked together to maintain the Wilkie-era cabins, create a townsite host program, maintain mountain trails, and carry out interpretation projects.

In 2003 the issue was raised over century-old hazardous materials left from the early mining days and their possible effects on air, water, and soils. Testing continues, with future governmental options as yet unknown. For those involved with the area, possible adverse effects of a cleanup also raise concerns. These could include damage to historical, archaeological, scenic, and wilderness values, which have competing legal protection. The complex mining history of Monte Cristo clearly is not over.