Mukilteo is one of the oldest settlements in Snohomish County and the first county seat. Situated on Possession Sound, the town is bordered on the east by Everett and Paine Field. The site, long home to a village of the Snohomish Tribe, was the location for the signing of the Point Elliott Treaty in 1855. Early Mukilteo entrepreneurs Morris Frost (1804-1882) and Jacob Fowler (1837-1892) established one of the first salmon canneries in Washington Territory and one of the region's earliest breweries. Japanese workers of the Crown Lumber Company and their families became an important part of the Mukilteo community from 1903 to 1930. Mukilteo Light Station near the Mukilteo-Clinton ferry dock, completed in 1906, is on the National Register of Historic Places. Mukilteo incorporated in 1947. Since World War II, the city's proximity to Paine Field and Boeing has influenced growth choices significantly. Annexation of acreage south of the city in 1980 and in 1991 expanded the population, which in 2010 was listed at 20,313. Expansion shifted the economic focus away from the waterfront, but in 2015 work began on a new ferry terminal and transportation center on the waterfront that were expected to revitalize Mukilteo's "Old Town."

Snohomish Village

People of the Snohomish Tribe set up a year-round village on the land spit and adjoining salt marsh that became Mukilteo. According to oral tradition, Dokwibuth the Transformer instructed inhabitants to move from this spot north to the mouth of the Snohomish River where they built the fortified village of Hebulb.

The meaning of "Mukilteo" has often been given as "good camping ground" but the Snohomish dialect of Lushootseed supplies the closest approximation: Muk-wil-teo or Buk-wil-tee-whu, "to swallow" or "narrow passage" (Dictionary of Puget Salish, 32). Chief William Shelton of the Tulalip Tribes described its meaning as a throat, a neck or a narrowing in a body of water. Mukilteo was a favorite meeting and camping ground well into the historic period.

George Vancouver and Charles Wilkes

Shortly before midnight on Wednesday, May 30, 1792, British Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798) anchored his ship the Discovery at the site that became Mukilteo. The following day, Lieutenant William Robert Broughton and botanist Archibald Menzies (1754-1842) briefly went ashore for exploration. They named the place "Rose Point" for the many wild roses growing there. Remnants of Rosa nutkana can still be found along the Mukilteo shoreline.

U. S. Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (1798-1877) left his mark when he anchored in the summer of 1841 and officially changed the location name from "Rose Point" to "Point Elliott" on American charts, honoring of U.S. midshipman Samuel Elliott.

Point Elliott Treaty

On Monday, January 22, 1855, territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) met at Point Elliott with 82 Native American leaders including Chief Seattle. In the presence of many tribespeople, a treaty was signed by which the Indians ceded their lands to the United States government in exchange for relocation to reservations, retention of hunting and fishing rights, and an amount of cash.

On May 2, 1931, the Marcus Whitman chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) placed a monument commemorating the event in front of Rose Hill School at 3rd Street and Lincoln Avenue. The school, an important landmark built in 1929, was demolished in December of 2010 and replaced with a modern 29,000-square-foot community center. The Point Elliott Treaty monument remains in place near its original location.

The First County Seat

In 1860 Snohomish County was still a part of Island County with government at Coupeville and court held at Port Townsend, Judicial District 3. While Emory C. Ferguson (1833-1911) placed his hopes on commercial possibilities at Cadyville (Snohomish), pioneer Morris Frost saw more potential at Point Elliott. Frost was then employed as customs officer at Port Townsend and Jacob Fowler operated a hotel at the upper end of Ebey's landing on Whidbey Island. Frost convinced Fowler to join him as a partner in operating a trading post and hotel at Point Elliot, a place both thought would grow quickly. Census and homestead records show that Frost and Fowler situated at the site in the summer or fall of 1860. Fowler began calling the place Mukilteo, returning to an approximation of the Indian place name.

Snohomish County was created by territorial legislature on January 14, 1861, Mukilteo becoming its pro tem county seat, pending official elections in July. The first commissioners meeting took place in Mukilteo in March 1861. Pending issues focused on building a connecting road from Snohomish to Woods Prairie (the future site of Monroe) and rejecting Fowler's request for a liquor license. At the second commissioners meeting, the county was divided into two voting precincts, ballots to be cast at Frost and Fowler's store and at Ferguson's home in Snohomish. On July 5, 1861, Mukilteo became the first county post office with Jacob Fowler chosen as postmaster on June 24th of the following year.

On July 9, 1861, voters decided 17 to 10 to establish the official county seat at Snohomish. E. C. Ferguson later recalled the event, telling how he had personally carried the record books back with him to Snohomish.

Some of Jacob Fowler's letters, now in the University of Washington's Special Collections, reveal life during those early years at Mukilteo:

"[November 2, 1860] It is lonesome up here and very quiet. Trade is very dull, but I live in hopes of it being better one of these days. ... [July 21, 1861] Our election is all over. It passed off very quiet, no fighting or drunkenness. I am a defeated candidate for auditor. Ferguson beat me three votes. We also lost the county seat by three votes. Some of our boys did not turn out and many was off at work. They gave me county commissioner instead of auditor" (Fowler letters).

Logs, Liquor, and Salmon

Situated across from Whidbey Island and offering easy trade with early Puget Sound mills, Mukilteo became an important trade site for the logging business. But Frost and Fowler sought a more diverse commercial base that did not depend entirely on the fickle lumber and shingle trade. For a time they exported cranberries to outlying areas.

Mukilteo took on a new enterprise in 1870 when brew master Jacob Barth set up one of the earliest breweries in Washington Territory in the ravine that became known as Brewery Gulch. The business incorporated in 1875 as the Eagle Brewery with Joseph Butterfield as proprietor and, by the following year, Frost and Fowler were running it. At its peak of production, the brewery produced about 15,000 gallons of quality lager beer annually. Fire destroyed the plant in 1882.

In 1870 a salmon-salting business also began under the directorship of men named Vining & Rheinbruner. In 1877 this operation became a salmon cannery built by George Myers & Co., one of the earliest of its kind on Puget Sound.

1890s and 1900s Development

Morris Frost did not live to see Washington become a state. He died in 1882 at 78 years of age. His hopes to see Mukilteo become the dominant port on Possession Sound never materialized. Instead Mukilteo grew moderately alongside the Everett development, the chosen site of East-Coast capitalist investors. By 1892, Mukilteo had a population of about 300.

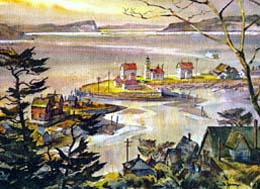

Mukilteo's development in the early 1900s mirrored the growth of other Puget Sound cities and towns of the period. In 1903 the Mukilteo Lumber Company plant was established, followed the next year by the opening of Mukilteo Mercantile. In 1906 the Puget Sound and Alaska Powder Company set up a plant in Mukilteo and in the same year, the Mukilteo lighthouse began operation. The powder plant exploded in September 1930 and was never rebuilt, but the lighthouse has remained an important architectural landmark since its construction. Now a National Register property, it continues to define the character of the Mukilteo waterfront.

Roads, Rails, and Ferries

The Point Elliott site was easiest to access by water routes, first by canoe, then by steamer, and later by passenger and car ferry. For local tribes, the waterfront site that became Mukilteo was an important crossing-over point connecting Whidbey Island and the mainland, a water route that continues to this day. And although the Great Northern rails were built along the coast in the 1890s, the railroad connection primarily was for freight, with limited passenger travel. Road connections from Mukilteo to other settlements continued to be a challenge for many years. An early road was made linking Mukilteo to Lowell, Snohomish, and Woods Prairie (present-day Monroe), but the construction cost of spanning seven gullies slowed progress on the road connecting Everett and Mukilteo. Now called Mukilteo Boulevard, this road was officially opened with a grand ceremony in 1914. The road still hugs the coast line, bordering three city parks and offering views of Port Gardner Bay as well as sought-after view property for residences and a few businesses.

In 1911 the Island Transportation Company began passenger-ferry service between points on Whidbey Island. Car ferries began in 1919 with the Whidbey I and the Central I making regular runs between Mukilteo and Clinton. For the next three decades ferry service was maintained by ships of the Puget Sound Navigation Company (the Black Ball Line) until 1951 when the company was purchased by Washington State Ferries.

Restaurants and ferry landings have long been good companions and the Mukilteo ferry landing was no exception. A tiny lunch room built by Howard Josh offered food, fishing tackle, and bait. It had become part of the landscape by the 1920s and evolved into the Ferry Lunch operated under several owners. Edgar and Richard Taylor (1918-2005) purchased it in the late 1940s and continued to run it as the Ferry Lunch for 22 years. They finally changed the name in 1970 to what customers were already calling it, "Taylor's Landing." Taylor's, at 710 Front Street, was sold to Ivar's in 1991 and became Ivar's Mukilteo Landing.

Mukilteo is traversed by two state highways. State Route 526 runs east from Mukilteo through Everett to Highway 99 and State Route 525 runs north from Highway 99 near Lynnwood to the Mukilteo ferry terminal. The Mukilteo stretch of SR 525 is also called the Mukilteo Speedway. In 1941 a viaduct was constructed over the railroad lines, near the ferry loading dock.

The Japanese Community

The Mukilteo Lumber Company, established in 1903, changed its name to Crown Lumber Company in August 1909. The business flourished for the next two decades. Many of its workers were Japanese immigrants who, with their families, lived in company housing in what was initially referred to as "Jap Gulch," later changing to "Japan Gulch" and then "Japanese Gulch." Although Everett's strong labor force held no quarter for cheap labor and other towns in the area drove out Japanese workers, Mukilteo residents came to terms with their Japanese neighbors and were able to live in harmony.

Most of the Japanese residents moved away when the Crown Lumber Company closed in 1930. One of them, psychology professor and decorated U.S. Army World War II veteran Masaru "Mas" Odoi (1921-2013), who was born in Japanese Gulch, returned many times to Mukilteo in his senior years to tell his story of the Japanese people who made their homes in the Gulch. Odoi remembered Mukilteo as a place of happiness and peace. He was responsible for creating a monument in memory of the Japanese community at Mukilteo and their harmonious relationship with other Mukilteo residents. Odoi's efforts helped spark creation of the Japanese Gulch Group in 2007, dedicated to the preservation of the Gulch's ecological diversity, wildlife habitat, and historical significance. In 2013 the City of Mukilteo acquired the property in order to develop it for outdoor recreation and preservation.

Wartime Growth

Paine Field -- the Snohomish County Airport -- was developed in unincorporated Snohomish County between Everett and Mukilteo, about five miles from the Mukilteo ferry landing. Begun as a commercial airport in 1936, Paine was converted to a military airfield and training site during World War II (1941 to 1946).

Taking advantage of Mukilteo's excellent deep-water harbor, good roads, and close proximity to rail lines, the U.S. government also acquired the former Crown Lumber Company site and constructed a large ammunition-loading complex on the site. At the peak of wartime use, workers numbered about 600, employed to transfer ammunition, bombs, shells, and nitroglycerine from rail cars to ships.

The Korean Conflict in 1951 reactivated military operations at Paine Field. In addition, at this time the federal government built 10 large fuel tanks on the Mukilteo waterfront, despite local opposition. The adjacent ferry terminal was modernized in the 1950s. The "Tank Farm," as it became known, officially closed in 1989 but the slow process of tank removal lasted for decades.

From its start Paine Field had a large impact on Mukilteo. In the 1960s it became home to a giant Boeing plant (the world's largest building by volume) producing the 747, 767, 777, and 787 aircraft, which in 2015 remained a mainstay of the area's economy. A steep railroad grade was built through Japanese Gulch from the rail lines at Mukilteo to the Boeing facility.

Incorporation and Beyond

Mukilteo voters approved an incorporation measure on April 29, 1947, and the official papers incorporating the community as a town of the fourth class were filed with the Washington Secretary of State on May 8, 1947. In the same election, Alfred Tunem (1896-1972) was chosen as the town's first mayor; he served until 1956. Mukilteo became a code city in 1970 when it adopted the state municipal code.

In 1970 the Mukilteo Biological Field Station began operating out of a small wood-frame building near the ferry landing that had served as government offices and housing during World War II. The building later became home to the Mukilteo Research Station, one of two field offices of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center (NFSC) in the Puget Sound region, where scientists could study marine life in both controlled and natural environments. The facility includes (as of 2015) a high-quality seawater system for fish rearing and study of marine species, an algae and zooplankton culture laboratory, a deep-water pier with easy access to other field-research locations, and specialized laboratories and equipment for studies on toxic substances.

Old Town/New Town/Old Town

After the city annexed acreage south along Mukilteo Speedway (SR 525) in 1980 and then the Harbour Point area in 1991, Mukilteo's economic and governmental center shifted away from the original town site on the waterfront, which came to be called "Old Town." But in the early years of the twenty-first century, significant changes on the Mukilteo waterfront returned a strong focus to that original town center. Facing budget shortfalls in 2003, the state transferred ownership of Lighthouse Park, constructed in the 1950s, to the city. Renaming it Mukilteo Lighthouse Park, the city redeveloped the park, adding lawns, art sculptures, historical markers and expanded picnic space. As of 2015, Mukilteo Historical Society, in partnership with the City of Mukilteo, is in charge of the lighthouse. An annual Lighthouse Festival is held with artists' booths, a parade, fireworks, children's activities, and the Run-A-Muk marathon.

The Mukilteo-Clinton ferry route is one of the busiest in the state ferry system, transporting 2.1 million cars and trucks annually. The inadequacy of an aging terminal led the state legislature to appropriate $68.6 million and the federal Department of Transportation to grant $4.7 million to build a new terminal at Mukilteo. Additional government funds raised the amount to $129 million.

The Port of Everett and the Tulalip Tribes worked closely with city and state officials to select the best site for the new ferry terminal. In early studies for the project, conducted in 2006 and 2007, a large shell midden and many Indian artifacts were discovered, carbon-dated to habitation about 1,000 years ago. As Daryl Williams, Environmental Liaison at Tulalip Tribes, explained to the press in 2012, "The Snohomish Indian tribe maintained a year-round village on the shoreline at Mukilteo for centuries" ("Indian Artifacts Found ..."). In the search, no burial remains were discovered. The decision was made to locate the new ferry terminal on the site of the old Tank Farm.

After the oil tanks at the long-close facility were finally removed, workers began demolition of the fuel-tank pier in July 2015, removing pilings and an estimated 7,000 tons of toxic creosote, 12,000 feet of old fuel lines, a large amount of asbestos, and tons of grass and organic material that had accumulated at the site over the years. Scheduled for completion in 2019, the new terminal was designed to be the major part of a transportation center uniting ferry service, city and county buses, and a Sounder rail station, all in close proximity to Mukilteo Lighthouse Park and Japanese Gulch trails.