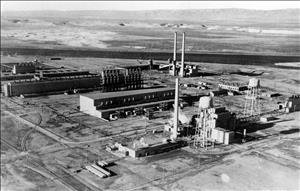

On February 23, 1943, a federal judge signs the Order of Condemnation for 625 square miles of land bordering the Columbia River near Richland and Hanford. This paves the way for the construction of the Hanford Engineer Works, part of the super-secret Manhattan Project. Thousands of residents will be evacuated to make way for a huge influx of new workers who will soon be working on manufacturing plutonium and uranium for atomic bombs.

Residents Stunned

The residents of Richland and surrounding areas were understandably stunned by the order when they receive registered letters on March 6 informing them of the condemnation of their homes and farms for undisclosed military purposes. Most were ordered to evacuate in 30 days. About 1,100 residents gathered at a mass meeting in Richland and adopted the following statement, which they released to the newspapers:

"In connection with the proposed evacuation of the Richland irrigation district, the 1,200 or more people living in this district want it plainly understood that they wish to take no action that would in any way jeopardize military necessity. They fully understand — in fact, insist — that at all times military necessity comes first. But the Richland irrigation district, a permanent and self-contained community with 6,000 acres of highly productive land and 300 farm families, is a heavy producer of vegetables for processing, fruit, poultry and dairy products, all of vital importance for military and civilian consumption for lend-lease operations" (Spokane Daily Chronicle, "Condemning").

In other words: Weren't they already contributing to the war? They went on to ask that they be "permitted to produce and harvest the 1943 crop if this is feasible." A few farmers were allowed to do so.

Agitated Knots of People

A reporter who visited Richland a week or so later said it was easy to find agitated knots of people on the main street making "angry and excited assertions" such as: "The government treats us worse than it treats the Japs" and "My son will come home from the war to find his home wiped out as if by an invader" (Spokane Daily Chronicle, "Richland Folks").

Yet the reporter said this was not the majority opinion. Most residents were resigned to the evacuation. The government tried to ease the distress by extending the evacuation deadline and ordering its real-estate appraisers to "use more tact and judgment" in setting buyout prices. In the end, only about 10 percent of Richland's population stayed to work on the project. Most took their money from the buyout of their property and moved to Kennewick or Pasco or left the region entirely. Meanwhile, new workers poured in. The population of Richland went from 247 before the condemnation order to more than 11,000 within a year.