Well known for his many books and publications on Seattle, past and present, Paul Dorpat has contributed more than 1,300 "Now & Then" features to The Seattle Times Pacific Northwest magazine. Dorpat came to Seattle during the turbulent 1960s to pursue a career as an artist. While teaching at the Free University, he became involved in publishing the Helix, an alternative newspaper, and arranging successful rock/jazz music festivals in Western Washington. He is one of three founders of HistoryLink.org, this online encyclopedia of Washington state history, and is an indefatigable chronicler of the local scene via both writing and photography. His book Building Washington (co-authored with Genevieve McCoy) received a Washington State Book Award (formerly Governor’s Writers Award) for 1999 as well as the Judges' Choice Award for the 1999 Literary Arts Section of Seattle’s Bumbershoot Arts Festival. In 2001, Paul Dorpat received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Pacific Northwest Historians Guild. In his own words, he's a "tourist in my own hometown."

Historian with Projects

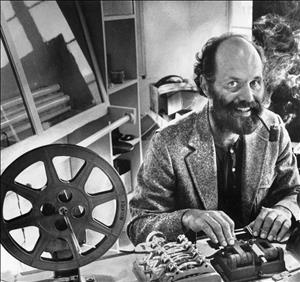

Seattle historian and photographer Paul Dorpat arrives for our lunch-time interview armed with two single-spaced printouts. Grouped into categories are dozens of projects Dorpat wants to accomplish in the final years of his life. He hands me the lengthy list of future assignments, knowing full well that I have been assigned to write about his past, not his future. But Paul is unabashed. He explains, "One of my older brothers died at 80. I figure that I have another 10 years." It’s apparent that I am not yet writing Paul’s ultimate biography.

Dorpat, who famously calls himself "a tourist in my own town," is one of the three founders (along with Marie McCaffrey and Walt Crowley [1947-2007]) of HistoryLink.org. Best known for his weekly "Now & Then" feature in The Seattle Times, he has amassed a broad and lengthy resume encompassing books, lectures, presentations, odd projects and -- in his own words -- "having fun."

Keeping Clam

Dorpat’s most immediate project -- though he multi-tasks on several at a time -- is completion of a biography of Ivar Haglund (1905-1985), the Ivar of the Seattle restaurant chain, Ivar’s Acres of Clams. Working title of the biography is Keep Clam: Ivar, Ivar’s, and The Culture of Clams. Paul asks about Ivar’s erstwhile clam-eating contests that, as it happens, I do know a little about, having judged several of Ivar’s clam-eating contests. Fact is, it isn’t easy getting Paul to talk about himself. He’s too busy interviewing the interviewer. Furthermore, it’s difficult to find anything that doesn’t interest this great bear of a man with a saint’s grizzled beard and a voyeur’s piercing dark eyes. He’d be a menacing presence if it weren’t for his reassuring bass voice that seems to resonate as if coming from a far distant chamber. It’s the voice of an Old Testament prophet, the voice of reason personified.

Preacher's Son

That voice is an inheritance come by honestly. Paul is the son of a preacher, the fourth and last son of the Rev. Theodore Erdman ("T.E.D.") Dorpat and Ida (or Eda) "Cherry" (Christiansen) Dorpat, born in Grand Forks, North Dakota, on October 28, 1938. As a teenager, he seemed all but destined to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a man of the cloth. He describes his father as having “a great booming voice” and having been superb at handling the business of managing a church. His mother, he says, was “witty.” He recalls that she wrote plays that were often presented at the church.

When Paul was 7, his family moved from Grand Forks with its community of staid German and Danish Americans to Spokane where he grew up, attended Lewis & Clark High through his junior year and then entered Concordia Academy and Jr. College in Portland, Oregon. “It was as a student at Concordia that I turned.,” he says. “I read church history and textual criticism and I also noticed that people without faith acted as well and often better than Christians did.”

Although assured by academic advisers that he had the makings of a good preacher -- if he’d simply apply himself -- chance stepped in. Dorpat slipped a spinal disc playing basketball and had to spend two months recuperating in bed. By the time he recovered, he had taken time to reassess his career path. He applied to Whitworth College and, with his mellifluous basso voice, he was able to secure a scholarship to sing with the choir and the school quartet.

Art's Lure

At one point in his college career, he ended up in a professorial role, teaching other undergraduates, taking on classes in English literature, philosophy, and psychology with a Ford Foundation Teaching Assistantship. Next stop was graduate school at Claremont, “the Oxford of the West.” But once again, illness intervened – it seemed. Stricken with what he calls “an hysterical illness, an undetermined dizziness,” Dorpat quit and never went back. He made the decision to become an artist and to also keep reading.

He moved to Seattle to try out the “big city” and also to be near an older brother, Dr. Ted Dorpat (1925-2006), a psychoanalyst and forensic psychiatrist. One of his first steps was to enroll in a Free University of Seattle sculpture class taught by Rich Beyer, later known for his many Seattle works, including the popular Waiting for the Interurban statue in the Fremont neighborhood.

Dorpat loved making art. "When painting," he says, "I would be so involved with the process -- oils and multi-media pieces -- that I didn’t know whether it was day or night." He often mixed media and notes that the collage work of Seattle artist Paul Horiuchi (1906-1999), influenced him.” Horiuchi is best known for his mural at the Seattle Center.

To support himself and his muse, Paul took “the only real job I’ve ever had.” Employed by the Seattle Children’s Home, he was assigned to work three days and three nights on a shift supervising adolescent boys, all wards of the court. He admits, “It was really tough.” Dorpat lasted six months before becoming more involved in the 1960s with the Free University as a curriculum coordinator. He taught as well. “Models and Metaphors,” a series of lectures, based on the writings of writers the popular, among them Marshall McLuhan, Owen Barfield, and Norman O. Brown.

The Helix Is Born

It was a creative, if a chaotic era and the University District, home of the Free University, was ground central for free-spirited activity. So it was no wonder that the example of many counter-establishment papers like the Berkley Barb set members of the Free University thinking about the possibility of publishing a paper of their own. The idea sparked during conversation between Dorpat and Unitarian minister Reverend Paul Sawyer.

In Rites of Passage, the late Walt Crowley recalls discussions of the project with Dorpat and a number of other University District regulars, including writer and critic Tom Robbins; Seattle Post-Intelligencer cartoonist Ray Collins; poet and song-writer John Cunnick; artists Maryl Clemmens, Karen Warner and Gary Eagle; University of Washington geneticist Jon Gallant; Free University’s Scott White; Seattle Folk Society Founder John Ullman; Seattle Jazz Society’s Lowell Richards; writer-critic Gene Johnson; Post-Intelligencer copy editor George Geazy, and recent Nathan Hale graduate Dan Murphy.

Among the many planning meetings held before the first issue was published, one was given to the difficult group task of deciding on a name. Dorpat remembers that while the group formed chairs in a circle in a borrowed storefront on the “Ave,” John Reynolds, a Far Eastern studies student, leaned into the discussion from a standing position and said, “Call it the Helix.” It was an allusion to the Watson-Crick description of DNA and also a way for the group to escape the advances of “Pepping Fred,” a name taken by Post-Intelligencer political cartoonist Ray Collins for a popular name given to a voyeur-flasher who, at the time, was stalking the University of Washiogton campus.

Time dragged on and eventually KRAB radio’s Nancy Keith dragged Dorpat into the Blue Moon Tavern and said, “Get on with it.” Dorpat borrowed $200 to rent a storefront at 4526 Roosevelt Way NE. It was there that he and his free-wheeling associates began producing a newspaper. The first 1,500 copies of the Helix rolled off the press March 23, 1967; the first copy sold for 15 cents. The fortnightly publication called itself “a community newspaper in the human sense.” The paper, with Dorpat acting as its “benevolent sheriff,” lasted through war protests, police crackdowns, wire taps, and assorted demonstrations, finally closing its doors with the June 11, 1970, issue. The paper carried this valedictory epitaph: “It is time. We are tired. Three years is a long time for an experiment to last.”

Rock 'n' Drop

Dorpat made time for related ventures, including guiding the early production of the Northwest’s own version of Woodstock -- the Sky River Rock Festival and Lighter Than Air Fair. He first participated in an elaborate work of performance art that went so well that it encouraged those involved to think about producing the festival. The "famous Piano Drop," a benefit for both Helix and KRAB radio, involved releasing a piano from a helicopter to see what noise that might produce. Dorpat recalls, "We wondered how it would sound when it hit whatever and we were fortunate that it missed the target – a wood pile on Larry Vanover’s acres outside of Duvall – and landed instead in the swamp-soft grass between the pile and the thousands of votives that nearly encircled it. My stomach rose to my throat as the piano dropped and fatefully missed its target."

The unmusical sound of the piano’s landing came to be known, in Dorpat’s words, as "a piano flop." The popular Berkeley band County Joe and The Fish donated their services to the Drop.

The Sky River festivals and the newspaper contributed to Dorpat’s growing reputation for “doing big things for hardly any money.” He says he lived off selling the Helix in dining rooms at Western Washington College (now University) while organizing the 10-day-long Multi-arts Festival on and off the campus. The festival featured exhibits, theater, performance art, and 40 bands and it ran a free food café for the duration, all on a student activities budget of $2,000.

His pursuit of “a life of freedom and fun” led Dorpat to apply for and succeed at obtaining grants and commissions. He helped put on benefits for charities at the Odd Fellows Hall. He painted walls at the Harvard Exit. He even opened “Acme Industries,” a short-lived promotions agency working out of a storefront on Capitol Hill.

Now & Then

During that time, Dick Moultrie, a friend from college, asked Dorpat to research the history of the old Merchants Café in Pioneer Square that Moultrie was working to reopen. This sparked Dorpat’s interest in Seattle history. At this time another friend, Michale Wiater, suggested that he apply for one of the federal CETA grants offered through the then-relatively-new Seattle Arts Commission.

Dorpat took his friend's advice, applied for and received a CETA grant to study the pictorial resources of Seattle history with the intent of making a film history of the city, to which he gave the working title “Seattle’s Second History.” He remarks, “I owe it all to Dick Nixon -- well, my start with studying regional history.” One thing led to another and with a group called “Mother Wit” Dorpat produced his first book in 1981 for the Mayor’s Small Business Task Force. It was titled 294 Glimpses of Historic Seattle and its Neighborhoods and Neighborhood Businesses. It was a paperback pictorial history using photos from his files or that he was able to borrow from private or public collections. The first run of 3,000 proved so popular that, by Christmas, Glimpses had gone into many additional printings and had racked up sales of more than 40,000 copies.

In its aftermath, Seattle Times columnist Eric Lacitis suggested to Dorpat that he might do a feature for the Times’ Sunday magazine. Dorpat pitched it to Pacific Northwest magazine editor Kathy Andrisevic, who said, “Let’s try it.” The first juxtaposition of photos and text appeared in 1982 and, since then, Dorpat has supplied more than 1,300 “Now & Then” features for the paper. On the occasion of his 1,000th publication, Dorpat wrote: “The pleasure of this work has been my association with heritage groups and other historians. When I began my study of regional history in the early 1970s, the people who gave their full time to the subject could be counted on the right hand of a careless sawyer – about two. Now we are legion.”

Dorpat has authored a bookshelf full of pictorial and historic books. Besides 294 Glimpses, his publications include 494 More Glimpses of Historic Seattle (1982); Seattle Now and Then, Volumes 1, 2 and 3 (1984, 1987 and 1989); As I Remember: A Personal Record for Washington Residents (1989); University Book Store: A Centennial Pictorial (1990), Building Washington (1998); Washington Then & Now (2007). The latter was co-authored with teacher/photographer Jean Sherrad. He wrote Building Washington with his wife, history professor Genevieve McCoy. It received the Washington State Book Award (formerly Governor’s Writers Award) for 1999 as well as the Judges' Choice Award for the 1999 Literary Arts Section of Seattle’s Bumbershoot Arts Festival.

In 2001, Dorpat received the “Lifetime Achievement Award” from the Pacific Northwest Historians Guild.

Picturing Wallingford

If Dorpat is correct with his predicted “10 more years,” he still has much to do before his journey is done. Among his self-generated assignments [in 2008] is “Wallingford Walks.” He takes the same walk in his neighborhood each day and takes pictures, about 500 per day, repeating previous ones. Thus he records the ever-changing scene, however incrementally, for eventual animation.

His other projects include a planned lecture tour of the state with Jean Sherrard; a history of the Seattle waterfront built on his 400-page report on that subject to the Seattle City Council; a personal reminiscence on the 60s and early 70s with a working title “Helix Redux,” done together with “Sky River Rock Fire,” a now 40-year-old video project begun in 1968 with the filming of the first Sky River; “The Forsaken Art Project," an exhibition and video on garage-sale art drawn from decades of collecting the stuff and interviewing many of those who sold it to him; a complete collection of Seattle Now and Then; plus putting his collections in good order with annotations for their eventual move to a public institution. “Photos seem to be two-dimensional windows into the past,” Dorpat says. “But once you enter them, they can take you anywhere.”

“Paul floats in and out of time, past and present," HistoryLink.org executive director Marie McCaffrey observes. "He is image-oriented. When he is around, his presence actively slows one's metabolism. He imparts a calmness, a sense of serenity."