During the 1890s Seattle, to boost its economy, actively sought an army post. The War Department also desired an army presence and encouraged the City to provide free land. The land was conveyed in 1898, construction began, and the new post was named in honor of General Henry Lawton (d. 1899), recently killed in action in the Philippines. Seattle expected it to be a major installation, but it remained a small post. The post is best known for events other than military accomplishments: a 1944 soldier raid on Italian prisoner camp, a court martial with injustices corrected more than 60 years later, a 1970 Indian demonstration and occupation, and struggles to convert the fort into Discovery Park.

A Small Post

In the 1890s an economic downturn encouraged cities such as Seattle and Tacoma to seek army posts to bolster their economies. Seattle lobbied for the forested Magnolia Bluff area, six miles from downtown, as a military post. The United States War Department indicated that a favorable response might be forthcoming if the site, some 700 acres, were donated to the government. This offer was made; the army selected it as a post location, the land was purchased and donated, and construction began in June 1898.

Named Fort Lawton in 1900, the installation remained a minor post throughout its history and never produced the benefits that Seattle had expected. One of the fort’s most significant events was unfortunately, an injustice in a 1944 court martial of black soldiers. Efforts to return the land to Seattle finally became a reality in the 1970s. The city effort to convert the fort into open land has been a battle between that use and other interests.

Military Development in Puget Sound

In 1890 a military team arrived in Western Washington to survey for a ship canal that would connect Lake Sammamish, Lake Washington, and Lake Union with Puget Sound. The survey reflected the War Department’s concern with military defense of the Puget Sound. The next year Lieutenant Ambrose B. Wyckoff (1848-1922) started the buildup with the purchase of a navy yard site in Bremerton. The Puget Sound Naval Station opened here in September 1891 with Wyckoff in command. In 1892 the construction of a drydock was initiated and the facility remains in active service as the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard.

On the army side, Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles (1839-1925), General of the Army, appointed a Fortifications Board in 1894 to identify effective coastal defense locations. The Fortifications Board selected 11 sites for coastal defenses to protect Puget Sound from the Spanish Navy. Coastal fortifications would be emplaced at Forts Worden, Flagler, Ward, Casey, and Whitman.

Seattle's Army Post

The Seattle Chamber of Commerce, anxious for its city to be part of the military buildup and bring dollars into a sagging economy, established an Army Post Committee to bring a post to Magnolia Bluff. The committee included prominent local business and legal profession individuals; James W. Clise (1855-1939), Thomas W. Prosch (1850-1915), and Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925).

Seattle was in competition with Tacoma for the post. Tacoma interests were proposing Point Defiance. The Magnolia Bluff location received a favored position when Brigadier General Elwell S. Otis (1838-1909), Commander of the Department of the Columbia, in his 1895 Annual Report, encouraged that a fort be built on the bluff. General Otis had a particular interest in maintaining order, stating that 100,000 people dwelled in this region and that some of them were restless, demonstrative, and oftentimes turbulent upon fancied provocation. With expected population growth, he believed, the need became more urgent. He concluded that Seattle was the best location for a post to halt lawlessness. The post could also provide defense for the important Bremerton Navy yard.

In support of the Seattle effort, Washington Republican Senator Watson C. Squire (1838-1926) introduced a bill on March 2, 1895, to establish a post, about 640 acres, on Magnolia Bluff. The land would be provided free to the government. The Tacoma advocates did not give up and went to the Secretary of War, who formed a board to look at both sites. The board selected Magnolia Bluff. Secretary of War Daniel Lamont (1851-1905) accepted the Seattle site on the condition that 704 acres be provided free to the government. A $50,000 construction appropriation followed.

Building the Fort

With the selection of Magnolia Bluff, Seattle had to acquire the land and give it to the government at no cost. The Seattle Chamber of Commerce acquired an initial 613 acres from 27 landowners at an average cost of $1 per acre. Some additional land brought the total to 703 acres, which was conveyed to the government in February 1898. A survey was undertaken by Port Townsend engineer Ambrose Kiehl, who stayed to supervise the clearing and construction. Kiehl moved his family into a house on the site.

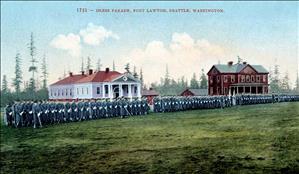

Construction of fort buildings started in June 1898 and included one double barracks, one double set of captain’s quarters, one double set of lieutenant’s quarters, two double set of Noncommissioned Officer’s (NCO) quarters, a Bachelor Officer Quarters (BOQ), and Quartermaster warehouse. Contractor Nichols and Crothers erected the wood-frame buildings. The army took possession of the first completed units in December 1899.

Fort Lawton

On February 9, 1900, War Department General Orders Number 20 named the post in honor of Major General Henry Ware Lawton. Lawton had served in the Union Army during the Civil War and then in the Indian Wars. In 1886 he led a force into Mexico to capture the Apache Chief, Geronimo (1829-1909). He saw action again in Cuba during the Spanish American War, where he received promotion to Major General. At the end of the Cuba operations Lawton received orders to the Philippines in March 1899. General Lawton headed the 1st Division in battle against insurgents there. During his first few months in the Philippines, Lawton achieved a number of significant victories. In the Battle of San Mateo, on December 19, 1899, General Lawton at a forward position directed the Americans, and was killed by a sniper’s bullet. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In addition to Fort Lawton honoring his memory, Lawton, Oklahoma, near Fort Sill, is named in his honor.

The first troops, the 32nd Coast Artillery Corps (CAC), Company C, arrived on July 26, 1901, under the command of 1st Lieutenant Mervyn C. Buckey (d. 1940). They were followed by a company of the 106th CAC. Despite the presence of coastal defense units, no coastal defense weapons were ever installed and CAC troops only garrisoned the post a short time. On May 9, 1902 Company B, 17th Regiment, arrived and the CAC troops departed. Fort Lawton would then be an infantry post until 1921 and then an engineer installation until 1941.

While a new post, Fort Lawton had few buildings and only a few hundred soldiers. It was not needed as a coastal defense fort and because the installation had little training land or ranges the infantry and artillery desired other facilities. In 1903 a halt to construction further reduced its value to Seattle. For the next few years few changes came to Fort Lawton. In 1908, 22 officers and 333 enlisted soldiers garrisoned the Magnolia Bluff installation. For most of its early history one or two infantry companies and some administrative staff were stationed here.

A four-section federal cemetery sits on the east side of Fort Lawton, surrounded by tall evergreen trees and the Army Reserve Center on the north. This cemetery received its first burial in 1902 and in 2008 is at its capacity of more than 900 burials. One former post commander, Brigadier General Frederick D. Atkinson (d. 1971), is buried here. Two unusual burials are a Word War II Italian soldier and a German POW (see below).

World War I and After

In 1917 elements of the 14th Infantry Regiment, 19th Division, departed for overseas duty. During World War I, the 6th Battalion, U.S. Guards (less three companies) infantry lived at the fort and pulled guard duty at the Port of Seattle. In 1919 troops of the 1st Battalion, 44th Infantry Regiment arrived and had garrison duties and riot-control duty during Seattle’s 1919 General Strike.

The infantry left in 1921 and elements of the 6th Engineer Battalion moved onto post. They performed construction and repair work that had been somewhat neglected. One of their more impressive projects involved the construction of a marble drinking fountain. Colonel (later Brigadier General) Clarence B. Blethen (1879-1941), Washington National Guard and publisher of The Seattle Times, presented it to the post on May 5, 1923.

A Citizens Military Training Camp (CMTC) was established in 1922. The CMTC offered military training to civilians without a service obligation. Cadets spent one summer month in a camp learning drill, physical fitness, and military skills. If a CMTC cadet attended four summer sessions he could be commissioned an officer. Few cadets opted to do this, so the program did not produce a large number of officers.

In 1925 horse stables were built and field artillery with horses became an interesting Fort Lawton addition. After just a few years the horse artillery left. On April 11, 1933 Company A, 96th Battalion Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) moved into one-half of a double barracks. The 96th soon became the 935th Company and moved to Boulder Creek, Chelan Forest. Two new CCC Companies, the 948th and 984th moved into the CCC area. They worked on local park projects, including trails and stone work at Carkeek and Colman Parks.

Apart from the CCC in the 1930s, Fort Lawton was quiet. In 1938 the army saw no need to stay and offered the post to Seattle for $1. The City Council turned down the offer, not having the funds to maintain the post. It is doubtful that Seattle could have retained the post during World War II, when the army established a Port of Embarkation in Seattle. The army probably would have reclaimed it. A building inventory in 1940 indicates that Fort Lawton had grown little since its establishment. The permanent structures included a rifle range, nine houses, eight barracks, post hospital, stables, a headquarters, and some temporary houses and other buildings.

World War II Era

The war brought new construction and increased activity. Temporary wood-frame buildings, 450 of them, were built to house troops awaiting transportation or those returning from overseas. On May 22, 1941, the post became a Port of Embarkation, processing the transport and return of soldiers to the Pacific Theater and Alaska. Fort Lawton processed 793,000 for embarkation and 618,000 debarkations or returnees. Also, fort personnel processed and shipped 5,000 Italian detainees to Hawaii.

Fort Lawton served as a Prisoner of War (POW) camp for 1,100 German POWs. In addition to the German POWs there was an Italian Service Units (ISU) compound.

Attack on the Italian Camp

In September 1943, Italian prisoners in the United States were allowed to join Italian Service Units (ISU) on behalf of the anti-fascist Italian government. This changed their status to co-belligerent, no longer prisoners of war, but not released. As members of the ISU, they wore American uniforms with Italian name tags, and they could go to the PX, drink beer at the canteen, and take off-post trips. Seattle families could bring food to them in camp or entertain ISU soldiers in their homes. All these privileges dramatically contrasted with the treatment of German POWs. Fort Lawton had one ISU company of 206 men, the 28th ISU Quartermaster Company.

Freedoms and privileges experienced by the Italians angered some soldiers and civilians with the War Department receiving complaints. Two junior hostesses at an eastern USO Club made the issue public when they refused to dance with Italians. Fort Lawton soldiers complained of Italians occupying tables at an already overcrowded PX cafeteria. Fort Lawton soldiers became angrier when seeing ISU personnel flirting with female PX workers and trying to get dates.

Compounding the situation, the ISU barracks were not separated from the main post. They sat just above the bluff in the northwest section of the post, next to a black soldier barracks. Two Port Companies (the 650th and the 651st) of black soldiers, who would soon be in the Pacific unloading supplies, had their barracks adjacent to the ISU compound. On August 14, 1944, these soldiers learned they were heading overseas the next day. That evening, parties included heavy drinking.

What happened later that night and into early morning is subject to considerable debate. Jack and Leslie Hamann have extensively researched the events, the Court Martial that followed, and the effort to bring justice to those denied it in 1944. The details are presented in Jack Hamann's On American Soil: How Justice Became a Casualty of World War II (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2005). This description draws upon Hamann’s findings.

The evening’s troubles begin with a confrontation between three Italians and three black soldiers who encountered each other and exchanged words. A fight ensued with one black soldier knocked out cold. A military policeman transported him to the hospital. The other Port Company soldiers returned to their camp and soon rumors spread fast as to what happened and seriousness of his injuries.

Then an angry group of Port Company men headed to the ISU compound and on the way picked up weapons including stones, knives, boards, and wood handles. Arriving at the ISU, the Port Company troops invaded the ISU orderly room and barracks. Italians and four American soldiers who carried out administrative duties with the Italians came under attack. A number of Italians escaped, ran into the woods on the bluff, and hid there. Thirty-two in the ISU camp suffered injuries, 12 of them serious including fractured skulls, knife wounds, and broken bones.

Frantic calls to the MPs met with a slow response with no help for about 40 minutes. When the MPs finally arrived they brought order and ended the brawl. The injured were removed to the hospital. The orderly room and a barracks had broken windows and doors, and weapons lay in the buildings and on the ground outside.

The next morning, at about 6 a.m., military policeman Private First Class Clyde Lomax (1923-1999) discovered the body of Italian Private Guglielmo Olivotto (1911-1944) hanging from a wire cable in the obstacle course below the ISU barracks. Some in his barracks reported that he was last seen jumping out of a window and probably running into the woods. His body showed only a few skin abrasions and no signs of a beating. The medical examination determined that he had been hanged, that it was not a suicide.

Aftermath

A very limited investigation was conducted the first morning. The victims could not identify their assailants. Also, the MPs who broke up the attack failed to identify the perpetrators. The weapons scattered about the scene were picked up and destroyed, with no fingerprints taken. Maintenance crews from the Post Engineers arrived and repaired the building damage.

In November, 43 Port Company soldiers faced a court martial. The army appointed Lieutenant Colonel Leon Jaworski (1905-1982) as the lead prosecutor, who would in 1974 achieve fame as the Watergate Special Prosecutor. Two attorneys defended the charged: William Beeks (1906-1988), who became a prominent Seattle attorney and Howard Noyd (b.1915), who later served as a federal judge. Three soldiers faced murder charges in Olivotto’s death.

Colonel Jaworski had some challenges finding witnesses to identify the guilty. The military police had been unable or unwilling to point out the guilty. The colonel also had a troubling report by Brigadier General Elliot Cooke (1891-1961), Army Inspector General Office, who found very serious shortcomings in the criminal investigation. The Court Martial came to a conclusion on December 18, 1944, with 28 soldiers convicted, one in the death of Olivotto. The convicted received long sentences, up to 25 years, and dishonorable discharges. These sentences were reduced during review; some of the convicted took part in army reentry programs to earn their way back into service and eventual honorable discharges, and President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972) granted clemency to many military prisoners in 1946 that included some of the men convicted for the August 1944 raid. Before the fourth anniversary of the raid all of the convicted had been released.

Unfortunately, the convictions resulted from less-than-creditable eyewitness accounts and the failure of the military police to identify the perpetrators. No physical evidence such as fingerprints had been obtained from the weapons. That Olivotto had no signs of a beating and no evidence linked the black soldiers to his hanging brought into doubt the link between the raid and his death. He may have been killed by someone not involved in the raid or possibly the medical exam incorrectly ruled out suicide.

After the war some of the convicted appealed their cases without success. Finally, after more than 60 years three families of the convicted, with Hamann’s evidence and assistance, and congressional help from U.S. Representatives Jim McDermott (D., Washington) and Duncan Hunter (R., California) appealed the convictions. A surviving soldier, Samuel Snow (1925-2008) joined the appeal. The Army Board for Correction of Military Records ruled that the prosecutor, Colonel Jaworski, had failed to provide the defense with critical information including General Cooke’s report. An apology came from the army and the provision for honorable discharges to replace the dishonorable.

On July 26, 2008, in a ceremony at Fort Lawton, formal apology was made to the families of the convicted. One of the two surviving court martialed soldiers, Samuel Snow, came to Seattle from his home in Florida and attended earlier events, but became ill hours before the ceremony and went to a hospital. His son attended in his honor. He was able to tell his father about the event, Shortly thereafter his father died. During the events surrounding the apology, Guglielmo Olivotto was not forgotten. His life was remembered at an Italian Mass in Seattle’s Chapel of St. Ignatius.

Death of German POW

On October 1, 1945, a German POW, Albert Marquardt (1907-1945), left the post on a paint detail to the Seattle Port of Embarkation. He and four other POWs drank lacquer thinner and became sick. Marquardt, the sickest of the group, went to the Fort Lawton hospital at 7.00 p.m. and died at 8.55 p.m. of poisoning. On his death certificate, accidental death is indicated, but some believe he drank a large quantity of thinner to commit suicide. Reports of his despondency over returning to Germany were offered.

Marquardt was buried in the Fort Lawton cemetery with a military headstone. He rests on the outer edge of the cemetery near the Olivotto grave.

The Seattle Port of Embarkation closed on October 1, 1949, with Fort Lawton continuing as a processing station for troops bound to the Pacific and Alaska.

Korean War and the Cold War

On Memorial Day, May 1951, a Freedom Grove of trees and a monument honored our war dead. The Korean War brought a flurry of activity as troops headed to or returned from Korea processed through here. In February 1953, the Fort Lawton Processing Center transferred half of its functions, the out-bound tasks, to Fort Lewis. The returnees continued to process here.

The first major construction project since World War II started with the building of 66 Capehart Houses at Buckey Heights (named to honor Lieutenant M. Buckey, Fort Lawton’s first commanding officer). The Capehart military housing program took its name from Senator Homer E. Capehart (1897-1979), R., Indiana whose bill to expand military family housing became law in 1955. The Capehart program had the government leasing the land, for a period of 55 years, to private developers who financed and built the homes and rented them to the military.

On February 13, 1957, a private firm, Fort Lawton Homes, Inc., leased 14.60 acres of post land, obtained a building loan, and had a groundbreaking ceremony on February 20, 1957. The homes were completed in October that year, opening to tenants' favorable comments. Many of them have good views to Puget Sound or the Olympic Range. However, nationally the Capehart program itself became troublesome with poor quality construction and poor management. The government took over the housing to correct the problems.

In 2008, these homes, presently occupied by Navy families, are scheduled for demolition to create more park meadows. The Navy families will move into new homes, nearer their Everett base, in Marysville.

During the summer of 1957, another construction project altered the fort’s appearance. The Army Reserve Center received a new training building, Harvey Hall. The building name honored Captain James R. Harvey (d. 1944), a Seattle resident who earned the Distinguished Service Cross in France on June 15, 1944.

In 1956 the Seattle area, with significant military bases and Boeing, received its first Nike anti-aircraft missile installations. By 1959 there were 10 Nike firing batteries defending Seattle. A Missile Master (later a radar known as BIRDIE replaced the Missile Master) to control all the firing batteries went into operation here in 1959. The thick-walled Missile Master building was sited between officers' homes. This required the demolition of Building 1, a single-family officers quarters built in 1904, and Building 5, a double-unit officers quarters completed in 1904.

The Missile Master building served to direct missile firings at the 10 Nike batteries. Operators in the “blue room,” with blue painted walls, would coordinate the batteries and their firing so two batteries would not fire at the same target while not engaging other targets. By 1974 the Nike batteries had deactivated and the BIRDIE radar shut down. In August 2008 the former Missile Master building is a large, heavily reinforced concrete structure awaiting demolition.

Fort Lawton ended its troop processing duties in 1959 when the returnee station went to Fort Lewis. Again, the post became very quiet and not necessary to the army’s global mission. In 1964 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (b. 1916) announced that 85 percent of the post would be surplus to the military’s needs and disposed of. The next year U.S. Representative Brock Adams (1927-2004), D., Washington, introduced a bill to transfer the surplus area at no cost to the City of Seattle. But just when it seemed Fort Lawton would finally revert to Seattle, the military proposed in 1968 its use as an Anti-Ballistic Missile base.

Citizens For a Fort Lawton Park

A citizens group, Citizens for a Fort Lawton Park, formed in June 1968 to fight the proposed ABM base and to advance the park cause. Donald Voorhees (1917-1989), later a federal judge, served as the organization’s chair. The group first took on the ABM basing and with direct assistance from U.S. Senator Henry M. Jackson (1912-1983) got the Department of Defense to drop the plan in December 1968. As the organization and others fought the ABM plans, positive efforts were underway for park development. In 1968 voters approved a Forward Thrust Park Bond Issue that included $3 million for a Fort Lawton park.

A major issue facing the park proponents was the cost to purchase the Fort Lawton lands. In an effort to gain from the sale of surplus military land, the government sought to obtain about 50 percent of its value. This would be more than Seattle could manage. Senator Jackson offered help by introducing a bill, called “the Fort Lawton bill” that provided surplus land at little or no cost for parks and recreation. In October 1970 President Richard M. Nixon (1913-1994) signed “the Fort Lawton bill,” opening the way for its acquisition at low or no cost for a park or recreation area. Communities across the nation would benefit from the bill, obtaining surplus federal lands for recreation and parks.

Indian Claims to Fort Lawton

Before President Nixon signed the Fort Lawton bill, on March 6, 1970, the United Indian People’s Council (later United Indians of All Tribes) laid claim to Fort Lawton land. The Council cited 1865 U.S. and Indian treaties granting surplus military lands to the original owners. Land would be reclaimed in the name of all Indians to pursue an Indian Way of Life. A Native American studies center, a university, school, and ecology center could be established.

On March 8, 1970, the United Indian People’s Council represented by 100 members and supporters appeared at the main gate. The assembled were led by Bob Satiacum (1929-1991) of the Puyallup Tribe, Bernie Whitebear (1937-2000) of the Colville Confederate Tribe, Leonard Peltier (b. 1944), later well known Indian activist. Supporters that brought world-wide attention to the event were Jane Fonda (b. 1937) and Grace Thorpe (1922-2008), activist and daughter of famous Indian athlete Jim Thorpe.

The Indian forces “attacked” the fort from various points. Some entered from the Puget Sound beaches, climbing the bluff. Other groups scaled the fences and all joined together on the post and erected a tepee. They came with cooking utensils and ready to occupy the fort. However, soon police of the 392nd Military Police Company were on the scene and arrested 72 “invaders.” They were taken to the post stockade, questioned, identified, and given letters of expulsion. The military police then escorted the “invaders” off post. Later Jane Fonda and 12 more persons went to and entered Fort Lewis, where they were arrested and given letters of expulsion. The Fort Lawton military police, unable to effectively prevent intrusions, requested assistance. Two truckloads of the 3rd Armored Cavalry from Fort Lewis reinforced the 392nd Military Police. The Armored Cavalry brought along rolls of concertina barbed wire, which was placed around the post perimeter.

The council then continued skirmishes with the military police and protests at the main gate, having set up a tent there. This continued for three months until the summer and agreement to end protest and negotiate. In July 1971 negotiations started between the Indians, City of Seattle, and U.S. congressional representatives. In November an agreement was reached with the United Indians for a 99-year lease to build an Indian cultural center in the Park. The groundbreaking ceremony took place on September 27, 1975, and the impressive Daybreak Star Cultural Center opened on May 13, 1977.

Discovery Park

With Fort Lawton becoming available, many groups requested pieces of land or the entire former post. During 1970, the Seattle Public Schools requested buildings for education, a request that would be denied. Some other requests that received rejections included: King County, the Navy, and the U.S. Coast Guard. The Army Reserve would be allowed to move into a military-retained section of post, called the 500 Area (the World War II temporary buildings here had numbers in the 500s).

In 1971 the General Services Administration offered 425.75 acres of Fort Lawton property to the City of Seattle. Mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935) responded that the City planned to make it into a park. Other uses were rejected, such as an Audubon Society request for 200 acres. The City contracted with highly respected landscape architects Kiley and Partners to deliver a Master Plan for park development.

On September 1, 1972, at an official ceremony, Tricia Nixon Cox (b. 1946 ), daughter of President Nixon, transferred 391 acres of Fort Lawton to the City of Seattle. Mayor Wes Uhlman received the land for Seattle. Senator Jackson was among the distinguished guests.

The first Master Plan was released in February 1972, but went through revisions and was published in 1974. The plan would create a park of 534 acres that would provide open spaces of natural setting with a tranquility not experienced in urban spaces. This would be a natural refugee of meadows, forests, wildflowers, tidal beaches, birds, and animals.

Also, by opening the formerly closed post, people would have access to the West Point lighthouse, the oldest one on Puget Sound. Over the years some 150 proposals for all or pieces of the park for other uses have been voiced. Discovery Park has held to its vision of few intrusions and the primary land use as a natural setting. A successor to Friends of Fort Lawton Park, Friends of Discovery Park (FRIENDS) have actively fought to stay the course on the original land-use plans.

A number of people thought the park should be named Fort Lawton Park to recall the post and its long association with the community. Donald Voorhees and the friends of the park preferred Discovery Park. This name recalled the Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798) exploration of Puget Sound in 1792 in his ship Discovery, and discoveries awaiting park visitors and especially children.

In 1972 some fort land on White Point went to Metro for a sewage treatment plant. The next year a World War II chapel, the Chapel in the Pines, was released to the park. In 1974 a proposed 18-hole golf course on the south bluff became another proposed option, which was rejected by the Seattle Parks Board and by voters.

Historic Preservation Concerns

Another 151 acres became surplus in 1975 and contained Fort Lawton’s most significant and historic construction, the homes and buildings around the parade grounds. This transfer put at risk these early buildings. The potential for negative impact or worse yet, demolition, loomed. In response the army undertook a National Register of Historic Places Inventory and Nomination. This document, completed in 1976, identified 24 buildings and the Parade Grounds as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). They were within a 25-acre site determined to be a Historic District. The Fort Lawton Historic District with its colonial-style architecture was NRHP listed.

These historic buildings and Historic District created conflict between those who desired to remove all or most buildings for open spaces and the historic preservation interests. To address concerns of the varying interests, a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the City, State Historic Preservation Officer, and federal government was formulated. This agreement allowed for use of the historic homes with guidelines regarding renovations and improvements so their early 1900s appearance would be retained. The agreement also included recording of the buildings through Historic American Building Survey (HABS). The HABS package, completed in 1981, contained measured drawings, photographs, and a Fort Lawton history. The MOA did allow demolition if it could be demonstrated that the buildings interfered with the park.

The Seattle City Council in December 1985 passed a resolution to demolish all but two of the Fort Lawton buildings (not including the homes). The demolitions began in 1986 with destruction of a non-historic gym (constructed in 1944) and hospital (constructed in 1902, but not determined historic). The demolitions and future razing drew protests from groups arguing for reuse and historic preservation.

In December 1987, the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation, a group dedicated to protecting the states historic treasures, filed a lawsuit in Federal Court. The lawsuit challenged the City Council’s plan to demolish all but two buildings, the administration and the 1902 guardhouse. In the suit it was argued that the City did not give serious consideration to other options. This violated the 1978 MOA stipulation that buildings would only be demolished if they interfered with the park. Further, the City had underestimated demolition costs. The Trust demonstrated that renovation would not cost more than demolition.

In February 1988 Federal Judge John Coughenor ordered the delay in demolition of seven buildings (the headquarters, Post Exchange, guardhouse, civilian employee quarters, and stables). The City would have to demonstrate full consideration of all the options. Following the court order, the City Council, at a June meeting, voted in a narrow 5-4 decision to save the buildings. A compromise was reached that the building exteriors be maintained, but not interiors. Additionally, the buildings would not be occupied as this would bring traffic and non-park visitors into the serene setting. The Seattle Historic Landmarks Board accepted the Fort Lawton Historic District as a Seattle Landmark.

The compromise has worked to date. The buildings have been painted and roofs maintained. Recently mitigation monies received from the Metro Sewage plant became available to demolish more non-historic buildings including a World War II chapel, the Chapel in the Pines, and the Missile Master building. Community protests have saved the chapel for its significant role in Fort Lawton life.

Discovery Park a Work in Progress

The Park trails and paths soon became popular venues with visitors enjoying the wildlife and serene setting. One trail, the Loop Trail, received the honor of being named a National Urban Recreation Trail.

In 1984, the Senator Jackson Memorial Viewpoint was dedicated at the flagpole near the administration or headquarters building. The Seattle Department of Parks continued to move towards the early goals. A 1986 Development Plan, based upon the 1972 and 1974 Master Plans, further refined and spelled out the Park vision. The primary goal remained to provide an open space of quiet and tranquility, where city residents find escape from urban noise and congestion. The plan further stated that the park should serve just this one mission so it can serve it well.

The 1986 Development Plan also restated its commitment to preserving the 1881 Lighthouse, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This feature, the plan stated, is to be welcomed as part of the park interpretative program and protected. However, the Metro West Point Sewage Plant would be better located elsewhere and the area restored to a natural marsh with associated access trails and interpretive signage.

In 1989 Donald Voorhees's death took an important park advocate. Robert Kildall, in his eulogy of Voorhees, called him the “Father of Discovery Park.” Kildall has carried on the Voorhees dream and protected the original concept while achieving some notable successes, including the effective natural screening of the West Point sewage plant.

More open space became a reality in 2000 with the army’s release of the 500 Area block wood temporary buildings. The demolition of these buildings and reforestation design by Seattle’s Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture has added 20-some acres to the park.

Homeless Housing

Fort Lawton again became controversial following the Base Reutilization and Closure (BRAC) 2005 recommendation to close the Fort Lawton U.S. Army Reserve Center. This 38-acre site on 36th Avenue W includes three main buildings, including Harvey Hall, honoring Captain James R. Harvey who received the Distinguished Service Cross in 1944, and the Leisy Center. The Leisy Center honors 2nd Lieutenant Robert R. Leisy (1945-1969), of Seattle, who received the Medal of Honor for heroic actions in Vietnam on December 2, 1969.

The BRAC process requires that opportunities for homeless housing be considered.

Various housing options are under consideration. They include a mixed-income community with low-income housing, market-rental-rate apartments, and 66 units for the homeless. Some Magnolia residents have expressed concern or opposition to the housing proposals, believing that they would lower property values.

Fort Lawton Today

Little remains of Fort Lawton, but the Historic District with its occupied homes, parade grounds, guardhouse, stables, and civilian employee house is impressive. The structures other than the houses are sealed with the exteriors retained and in August 2008 in good condition. The nearby Capehart housing will be demolished once Navy housing becomes available nearer the Everett base. The historic family housing is planned to remain and leased or sold to private individuals.

The cemetery receives respectful care and maintenance. Families come to visit loved ones and honor our veterans. On the edge of the cemetery is the Olivotto grave marked with a broken column representing a life broken in half. Nearby rests the German POW Alfred Marquardt. The Italian barracks and the black troop barracks are gone.

The memory of Fort Lawton will have to come from histories and photographs, as Discovery Park reaches towards its goals set 40 years ago.