Vancouver, located in Clark County in the southwestern part of Washington state, lies along the North Bank of the Columbia River, near its confluence with Oregon's Willamette River. The site was originally inhabited by Chinook Indians. The city is named for George Vancouver (1758-1798), the British explorer who mapped the Northwest coast in 1792. As the oldest non-Indian settlement in the Pacific Northwest, Vancouver perhaps celebrates its history more than most cities. A short walk from downtown is the site of the 1825 Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver, the 1849 United States Army Barracks including Officer's Row, the shipways from the World War II Kaiser shipyards, and Pearson Field, the oldest continually operating airfield in the West. Esther Short Park in the heart of the city, named after a redoubtable Vancouver pioneer, is the oldest public park in the Northwest. Near the park is the state's first Roman Catholic cathedral, which held the title of St. James Cathedral until 1907 when the See and the bishop were transferred to Seattle. The city's first industries were wood products, bricks, and a brewery. Clark County with Vancouver as its trading center also became known as the prune capital of the world. Vancouver experienced rapid growth during World War II, with two new firms, the Kaiser shipyard and Alcoa Aluminum, providing many new jobs. During the postwar years the city went into decline, but in the past 20 years has experienced phenomenal growth through annexations and fed by the arrival of more than 300 high-tech firms. Vancouver is, in 2009, the fourth largest city in the state of Washington.

First People -- The Chinook

For hundreds of years before Western explorers intruded on their shores, the Chinook Indians had lived along the banks of the Columbia River, which they called the "Wimahl," or "Big River." The extended tribe lived in relative abundance, enjoying readily accessible food from the river's rich salmon runs, plentiful plants and berries, and a mild climate. Freed from the necessity of struggling for subsistence, the Chinook became prolific traders, unrivaled in the western half of the continent. Chinook traders in large canoes carved from single cedar logs roamed a network of waterways that spread like a spider web for hundreds of miles along the coast, inland to Puget Sound, Hood Canal, the Chehalis River, and even on to the plains. Such was their dominance of trade that a specialized trading lingo, called Chinook Jargon, was eventually used by tens of thousands of coastal Indians and, later, by non-Indian trading partners.

The Chinook's first contact with non-Indian people may have been in 1792, when the Columbia Rediviva, an American ship captained by Robert Gray (1755-1806), made its way up the river. Gray, who named the river after his vessel, was soon followed by a British longboat dispatched by Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798) and commanded by Captain William Broughton (1762-1821), which entered the Columbia in November 1792. Over the next several decades, Chinook society was opened to the influence and predation of the Western world, and, like so many other Native cultures, was decimated by disease and rapidly overwhelmed. Lewis and Clark counted approximately 400 Chinooks living around Cape Disappointment in 1805, but by 1830 only about 30 or 40 remained. Most of the others were dead, victims of infectious diseases introduced by whites.

After a long struggle, on January 3, 2001, descendants of those Chinook who survived the incursions of the Americans and the British finally were granted federal recognition as a tribe. However, in July 2002 the Bush Administration revoked that status, claiming that the Chinook did not qualify for recognition because of a long gap in their history, from about 1880 to 1930. A congressional decision on reinstating tribal recognition is pending (as of August, 2009).

Fort Vancouver and the Hudson's Bay Company

Thirteen years after Captain Broughton entered the Columbia, Lewis and Clark passed through what is now Clark County in November 1805, and then again on their return trek in the spring of 1806. They spent a total of nine days in the area and pronounced the broad valley to be the best site for habitation west of the Rocky Mountains.

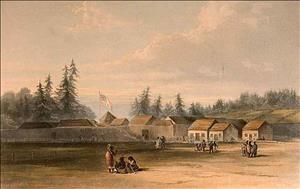

The British-owned Hudson's Bay Company opened Fort Vancouver on the future site of the City of Vancouver in March 1825, but this was not its first venture on the great river. In 1821, the company had absorbed its fur-trading rival, the North West Company, and acquired all the latter’s Pacific Northwest trading posts. These included Fort Spokane, near the present location of the city of Spokane and Fort George, near the mouth of the Columbia in what is now Oregon.

By the time Fort Vancouver was established in 1825, Hudson's Bay Company dominated the fur trade in North America. Each trading station was kept stocked with items that would be exchanged for pelts, primarily beaver, brought in by trappers and Indians. Among the more popular trading items were staples such as coffee, tea, and sugar; wilderness necessities like guns, axes, hatches, snares, and knives; and items that were both useful and decorative, such as buttons, blankets, cloth, and mirrors. After each trading season the supply of barter goods would be replenished, either manufactured on-site or requisitioned from the company's headquarters in London.

Fort Vancouver was an attractive destination for early settlers, offering safety, security, and supplies. The company was not openly hostile to the new American arrivals, but urged them to settle south of the Columbia River in the broad Willamette Valley. From the 1818 Treaty of Joint Occupation until the Oregon Treaty of 1846, Great Britain and the United States jointly occupied the area, with neither having a legally binding claim to ownership of the land. The Hudson’s Bay Company believed that the Columbia River was the natural boundary between the two nations, whereas the Americans thought that latitude 54 degrees 40 minutes north should be the boundary. In 1846, the Oregon Treaty set the border between the British and the Americans at the 49th parallel, far to the north of Fort Vancouver, while promising that:

"In the future appropriation of the territory south of the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude, as provided in the first article of this treaty, the possessory rights of the Hudson's Bay Company, and of all British subjects who may be already in the occupation of land or other property lawfully acquired within the said territory, shall be respected" ("The Oregon Treaty, 1846").

The pledge to respect the Hudson's Bay Company's existing "possessory rights" to land south of the 49th parallel was to prove illusory, however, and the company's remaining years at Fort Vancouver were numbered.

A mark left on the city by the Hudson's Bay Company is the designation of “Plains," a British term for areas without trees in a forested region. Upriver from the fort were grist and lumber mills. The road from the fort to this plain was known as the "Road to the Mill Plain." The Second Plain was where Burnt Bridge Creek crosses Fourth Plain. The Third Plain was near 112th Avenue. The Fourth Plain from the river was where Orchards is today. The road to the Fourth Plain ran through the Second and Third plains on its way. The only remnant of the Fifth Plain is Fifth Plain Creek.

Enter the Americans

The first American of note in the Fort Vancouver area was Henry Williamson, who laid out his land claim west of the fort in 1844 and platted a small town that he called Vancouver City. Williamson went one step further -- he registered his claim and the town at the federal courthouse at Oregon City, Oregon.

When Williamson ventured off to California, he left his claim under the supervision of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Amos Short (1808-1853) and his wife Esther Clarke Short (1806-1862), arrived from Pennsylvania with their 10 children shortly after Williamson left and settled down on his claim, building a cabin very near where the railroad bridge stands today.

A Witness Tree and a Shooting

In 1846, Amos Short measured his land claim from a "witness tree" (a tree used by surveyors to establish a corner of a section of land) by carving his initials in a cottonwood that stood near the bank of the Columbia River. This tree became a legal landmark in property disputes and the starting point from which much of Southwest Washington was surveyed. The old tree finally toppled on June 27, 1909, and two years later the remains drifted away down the river.

The Hudson's Bay Company did its best to drive the Short family away, burning their cabin, plowing under their crops, and putting the family on a boat to Linnton, Oregon. But the stubborn Shorts kept returning to their claim. Eventually a company representative, Dr. David Gardner, and two Hawaiian workers were sent to deal with Amos Short. A quarrel ensued, and Dr. Gardner was shot and killed. Amos Short pleaded self-defense and was found not guilty.

The Short Family Perseveres

Short went on to become a probate judge, a forerunner of today’s county commissioner. One of his duties was to decide land ownership issues, and he judged that he himself was the legal owner of Williamson’s land claim. In 1850, Short traced over the plat that Williamson had made of Vancouver City and renamed it Columbia City, which it remained until 1855.

On January 19, 1853, Amos Short drowned when his ship, the Vandalia, sank at the mouth of the Columbia River on a return trip from a sales expedition to California. Upon Amos's death, Esther found that Willliamson’s original claim was intact and that both the Catholic Church and the United States Army also had claims on the land. She filed her Affidavit of Settlement and Notice of Claim and returned to her businesses in Vancouver, but her title was hopelessly clouded. Her subsequent endeavors to resolve these land issues helped shape the city of Vancouver.

Esther Short granted permission for a ferry boat to land on the corner of her land claim and then built a restaurant and hotel there. When Esther Short died on June 28, 1862, she left to the City of Vancouver a section of her land to be used as a town plaza, now known as Esther Short Park. She willed the waterfront portion of her property to the city to be a public wharf, and left the remainder of her estate to one daughter, Hannah (1850-?). The dispute that arose among her other children over the distribution of the estate lasted for years and was not settled until 1880.

The British, the Americans, and Ulysses S. Grant

The United States Army arrived at Vancouver in 1849 and began building officers’ housing on a rise above the Hudson’s Bay Company fort, calling it Columbia Barracks at first but later changing the name to Vancouver Barracks. Amos Short rented out his oxen and wagon to haul the building materials, and soldiers were paid an extra dollar a day to build log houses on the site that today is called Officer’s Row.

Despite its unhappy experience with the determined Short family, the Hudson's Bay Company had some early success preventing settlers from squatting on company property. But after 1849 a flood of newcomers swarmed onto the land near the company fort and laid claim to it under the Land Donations Act of 1850.

Along with the new settlers came the Army's 4th Infantry Regiment and a Brevet Captain named Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), who would spend the next 15 months as regimental quartermaster of the military base. Grant went on to victory and fame, first as head of the Union army in the Civil War (1861-1865) and later as the nation's 18th president (1869-1877). He would not be the last army officer to serve at Vancouver Barracks before assuming positions of high leadership.

Meanwhile, the company's vigorous protests against the encroaching settlers had little effect. U.S. officials took the view that any such "trespasses" were subjects for the territorial courts, which, of course, were dominated by the settlers. Even after its royal license expired in May 1859, the Hudson's Bay Company sought to protect its interests, but by September 1860 the federal government's official surveyor had subdivided the land claimed by the Hudson's Bay Company (about 33,000 acres) "to the great satisfaction of the settlers …" (Fort Vancouver: Historical Background).

Growth of a New City

Congress approved the formation of Washington Territory in 1853, and in 1855 the Territorial Legislature formally changed the town's name from Columbia City to Vancouver. Under its new name it became one of the territory's first incorporated cities on January 23, 1857. The first mayor, Levi Farnsworth, was a shipbuilder from Vermont. He later served as a representative to the Territorial Legislature, being elected to that body at the age of 71. Members of that early city government appear to have been somewhat lax in their duties, as the town clerk threatened to fine members for non-attendance at meetings. The first ordinance, forbidding liquor sales on Sunday, would not be passed until March 28, 1858.

Businesses began to grow along Main and Washington streets. A handsome post office and courthouse graced downtown, as did the tower of St. James Cathedral. Taking advantage of good springs of water, the Vancouver Brewery opened for business in the 1850s. Henry Weinhard (1830-1904) purchased the plant in 1858 before going on to earn lasting fame and fortune with a new brewery in Hood River, Oregon.

During the Spanish American War (1898-1899) the commanding officer of the barracks, General Thomas Anderson (1836-1917), led the troops going to the relief of Admiral Dewey in the Philippines. This was the first time American troops had left the North American continent to fight a war. When news arrived of the victory at Manila, the brewery sent off 300 cases of beer for the enjoyment of the troops. The Filipino insurrection (the Aguinaldo Insurrection) that followed kept the troops and General Anderson in the Philippines until 1902.

The Vancouver Brewery would prosper for many years, converting to a soda bottling plant during Prohibition, but returning to brewing under several owners after Prohibition was repealed. In 1985 the brewery was abandoned and became an eyesore, and in 1995 the city bought the property and demolished the structures.

Trade, Manufacturing, and Agriculture

From its start, Vancouver was the main trading center in Clark County, drawing farmers from around the region. By 1867 the city boasted seven general merchandise stores. An abundance of trees in the area led to the development of companies that manufactured wood products, including staves and barrel kegs. Brick manufacturing also took hold, with a local brickyard supplying a million bricks in 1873 for construction of the Providence Academy, a Vancouver landmark.

The city's waterfront boomed during the last decade of the nineteenth century, as products from the nearby mills were loaded onto commercial vessels for shipments to faraway cities. An 1891-1892 directory listed Vancouver as having five sawmills, two sash and door factories, a box factory, three brickyards, and the brewery. The Panic of 1893 brought progress to a virtual halt, but business picked up again after the crisis had passed.

Another important enterprise during the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth was the cultivation of prunes, which had its start in the Vancouver area in the later 1870s. In the days before canning, prunes were dried and packaged in private plants for shipment to the East. In 1900, Clark County shipped 50 carloads of prunes, with figures reaching 16,000 tons in the following 10 years. By World War I, the Washington Grower’s Corporation was formed, replacing private plants as the main prune processor, and by the early 1920s, Clark County was known as the prune capital of the world.

Mother Joseph and the Sisters of Providence

An important figure in the city's early history was Mother Joseph, born Esther Pariseau (1823-1902), who arrived in Vancouver in 1856. Under her leadership, the Sisters of Providence built an academy to school the children of the Territory, including orphans. When completed in 1873, it was the largest brick building north of San Francisco. She also founded Saint Joseph’s Hospital, which for many years was the only hospital in the region. It has evolved into the Southwest Washington Medical Center. Financed by begging expeditions, Mother Joseph established hospitals, academies, and orphanages throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Mother Joseph died in January 1902. The last words on her lips were to urge her sisters to work for the poor. Her gravesite, in St. James Acres on Fourth Plain, is a National Historic Site. On May 1, 1980, a bronze statue of Mother Joseph was dedicated in the rotunda of our nation’s Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

Early Transportation Links

Through the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Vancouver steadily developed. The last spike of the North Bank Railroad (the first rail line east through the Washington side of the Columbia River Gorge) was driven on March 11, 1908 and the line reached Vancouver. On June 25, 1908, the railroad bridge across the Columbia River was completed, at last incorporating Vancouver into the region's transportation network. That brought a rush of growth to the city, including a Carnegie library, new churches, and, in 1916, the new Post Office Building on Daniels Street.

The boom brought to the fore the need for a wagon bridge across the Columbia River, a need reinforced by the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exhibition in Portland in 1905. The ferries crossing to that event were packed to capacity, and passengers had to endure long waits. Vancouver business leaders began a vigorous campaign in support of a wagon bridge, parading through downtown Portland on March 2, 1912. They carried banners reading, “We need the bridge and so do you. We’ve done our part now you come through.”

A huge setback to the project occurred a year later when Governor Ernest Lister (1870-1919) vetoed the finance bill for the bridge and the Legislature sustained his veto. Determined to have the Interstate Bridge, Clark County joined with Multnomah County in Oregon, and together they built a toll bridge to span the river. It opened on St. Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1917, just in time for World War I.

The Great War and the Great Flu Pandemic

To supply ships for World War I, the Standifer Construction Company built two shipyards on the Columbia River in Vancouver, one for wooden ships and one for steel ships. The yard for wooden ships was just west of the Interstate Bridge, and the Kineo, its first ship, was launched on May 30, 1918. The yard for steel ships was about a mile to the west, just downstream from the railroad bridge. Both yards would build ships until 1921, when the property was sold to the City as a site for a municipal dock.

On the military reservation, The Spruce Production Division rapidly organized under the direction of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The largest spruce mill in the country, it was purpose-built to provide spruce for airplane manufacturing and Douglas fir for ship construction. Thousands of men, civilian and military, worked in the division, but when the Armistice came on November 11, 1918, all production was stopped within two days.

Because Vancouver and Clark County were deep into the Spanish flu epidemic, there were no public celebrations to note the Armistice that ended World War I. A city-wide shutdown was in effect forbidding all public gatherings, and even the churches were closed. From October 5 until November 15, 1918, there was little reported in the local papers other than news of the pandemic.

The 1920s -- Prohibition and the Klan

Prohibition began in Washington state at midnight on December 31, 1915, more that four years before the nation went dry under the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act. The Prohibition years which followed the World War I brought more than just sobriety to the Northwest. Vancouver had depended on its brewery for jobs, and fruit growers relied on brandy distillers for income. Adding to their troubles, prune growers suffered large losses from poor weather and competition from California orchards. To help the industry, a booster group called the Prunarians organized and put on a Prune Festival, complete with a Queen of Prunaria. Their motto was, “We’re full of prunes.” But despite their best efforts the market for Washington's prunes steadily decreased and eventually dried up.

Not all organizations were as benign as the Prunarians. The Ku Klux Klan made its first appearance in Vancouver on March 11, 1922, and it grew in social and political power by representing itself as a patriotic Christian organization. In August, 1924, the Klan held a huge open-air ceremony, with a flaming cross as the centerpiece. Some 500 clansmen in full regalia attended, and a crowd estimated at 10,000 looked on. The Klan continued to grow in power through the lawless Prohibition years. In 1926, the Klan-backed candidate for sheriff was found to have evaded taxes, and his opposition, independent candidate Lester Wood (1894-1927), was elected. Just five months after he was sworn in, Sheriff Wood was shot to death near Dole during a moonshine raid. Luther Baker (1868?-1929) was later hanged for the murder.

The Depression and the New Deal

Wall Street crashed on October 24, 1929, and the Great Depression began. On October 30, Vancouver’s Mayor, John P. Kiggins (1868-1942), ordered a city hall to be constructed at Washington and 8th streets, but it was to be built to office building specifications in case it had to be sold quickly.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president 1932 and in 1933 the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was passed, bringing the end of Prohibition and the return of Vancouver's brewery. Among the many programs the federal government set up to battle the Depression was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Under this program, young men and women from families on relief were put to work at a salary of $30 per month, $25 of which was sent home to their families.

A Famous General and an Epic Flight

The regional CCC was headquartered in the Vancouver barracks and was under the command of General George C. Marshall (1880-1959) from 1936-1938. Marshall went on to later fame as chief of the general staff under President Roosevelt, secretary of state under President Harry Truman and recipient of the 1953 Nobel Peace Prize. Marshall supervised 27 CCC camps in the Northwest that worked on such projects as the construction of forest fire lookouts towers, telephone lines and roads, and recreational areas, as well as a fish hatchery along the Evergreen Highway. When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, the nation's attention was turned to war production, and the CCC was eliminated by an act of Congress in July 1942.

On June 20, 1937, General Marshall had the honor of welcoming three Soviet aviators -- pilot Valeri Chkalov, navigator Alexander Belyakov, and copilot Georgi Baidukov -- who landed at Pearson Field after completing the first non-stop transpolar flight from Europe to America, an epic effort that kept them in the air in a Soviet ANT-25 airplane for nearly 64 hours. Vancouver enjoyed a bright moment in the world’s press, and a joint American-Russian monument stands on Pearson Field to mark the achievement. In the years since, Vancouver has maintained a special relationship with the Russian people.

Hydropower, Heavy Industry, and Housing

The opening of Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River in 1938 brought two major industries to Vancouver. Drawn by access to cheap electrical power, the first to come was Alcoa, which built its Vancouver Operations aluminum plant two and a half miles west of the city. On September 23, 1940, the massive plant produced the first aluminum ever to be manufactured west of the Mississippi River.

In early 1942, shortly after the onset of World War II, the Kaiser Corporation announced plans to build a shipyard on Hidden Farm at Ryan’s Point on the Columbia. Industrialist Henry Kaiser (1882-1967) had observed the property as he had traveled up the river during dam construction and recognized it as a good site for building ships. The Vancouver shipyard opened in early 1942, and turned out more than 140 ships and two drydocks during World War II.

War work brought a huge influx of new residents and the Vancouver Housing Authority was set up to help accommodate the thousands of people who poured into Clark County from around the nation. The authority built six major housing developments: Fruit Valley, Burton Homes, Bagley Downs, Fourth Plain Village, Ogden Meadows, and McLoughlin Heights. McLoughlin Heights was the largest wartime housing project west of the Mississippi. The secretary of the housing authority was Douglas Elwood Caples (1900-?), who was also Vancouver's city attorney. Just as the federal government forbade discrimination in hiring, under Caples guidance, the housing authority did not discriminate in the allocation of housing.

Integration, Then and Now

The African American population of Vancouver grew from 18 in 1940 to nearly 9,000 by 1945. Segregated housing during World War II led to the creation of a local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1943. It soon joined hands with other groups, such as the Vancouver Civic Unity League, to address housing segregation and to ensure that African Americans could find permanent housing in Vancouver after World War II ended. After a 1946 survey found 77 percent unemployment among black family heads, the NAACP worked with others to address the problem. These efforts contributed to the passage of the 1949 Washington State Law Against Discrimination in Employment.

At the end of the war, the housing authority obtained an $80,000 mortgage and bought the entire McLoughlin Heights project, which it dismantled to make way for a new group of neighborhoods. On New Year’s Eve, 1949, McLoughlin Heights was annexed into the city of Vancouver. One by one, the other wartime developments also became part of the city.

In 1952, the city created the Mayor's Commission on Open Housing. It had a diverse membership, which labored diligently to ensure that housing was available for all on a non-discriminatory basis. Complaints of discrimination were quickly handled. Florine Dufresne (1907-2003), one of the early members, said in an interview with the Center for Columbia River History,

“We were never confrontational, but listened to complaints, answered people's questions, and appealed to people's good will" (Florine Dufresne interview).

Decline and Recovery

The national highway system arrived in Vancouver when Interstate 5 was formally opened on March 31, 1955, with Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966) cutting the ribbon. The highway closed Vancouver's 5th Street, which had been a major arterial and the only road across the military reservation. To make matters worse, it provided no exit to downtown. The core of the city began to die, and the rise of shopping malls lured many merchants away from the city center. Urban renewal in 1965 removed most downtown housing, with residents relocated to other areas. The population entered a long decline and the downtown withered.

The Army began to rid itself of surplus property on the military reserve during the decades of the 1960s and 1970s. The area of the reserve north of the parade grounds was turned over to several government entities, including Clark County, Clark College, the Washington State Department of Transportation, and the Vancouver School District. An ambitious planning document, “A Park For the People,” was published by planners for those agencies. It assured the public that the green expanse of the former military reservation would be used for the benefit of the public without sacrificing its beauty. In 1987, Officer’s Row was transferred to the city, and in 2008 the West Barracks, including the hospital and the 1917 Red Cross Building, were also signed over.

Growing for the Future

During the past 20 years, Vancouver has experienced phenomenal growth, fed in part by the arrival of more than 300 high-tech businesses to the region, including such industry leaders as Intel, Hewlett-Packard, and IBM. Vancouver grew rapidly through annexation in the 1990s, expanding its city limits by over 30 square miles and adding almost 100,000 residents.

The City's aggressive annexation policy culminated in the Vancouver Mall Annexation of 1993 and the Cascade Park annexation of 1997. The latter, completed on January 1, 1997, was the largest annexation in state history, adding 11,258 acres and 58,171 residents and making Vancouver the fourth largest city in the state. These additions, together with the 192nd Street and Mill Plain Boulevard extensions and the redevelopment of the downtown core, have forever changed the face and the economy of the city. Having grown from a frontier trading post to a booming metropolitan area, Vancouver now stands poised to prosper in the twenty-first century.