Originally the site of a Chinook Indian village, the small city of Ridgefield in Clark County grew up on the banks of Lake River, a slow slough of navigable water that starts in Vancouver Lake and flows north and slightly west before emptying into the Columbia River. Ridgefield lies 10 miles north and a little west of Vancouver, the county seat. The city slopes up a gentle incline from the riverbank to elevated highlands on the east. Although the level of Vancouver Lake and the flow of Lake River have been greatly altered by dams and development, the river remains navigable 12 months a year. The Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge Complex lies between the town and the powerful Columbia River three miles to the west. While in earlier times Ridgefield weathered periods of very slow growth and economic stagnation, in more recent years it has seen rapid development as more people are drawn by its rustic charm, natural setting, and proximity to larger population centers. Ridgefield is classified as an "optional code city" under state law and now has a city council-manager form of government. It occupies an area of approximately six square miles and its population as of April 2009 was 4,215, more than double what it had been in 2000.

First Peoples

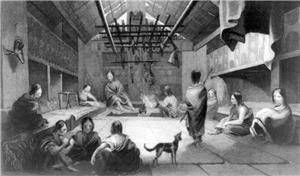

Archaeologists using carbon-dating techniques have found traces of human presence at the current site of Ridgefield as long ago as 2,300 years. The first permanent settlement for which good evidence exists was that of the Cathlapotle people, a Chinookan-speaking group that thrived in the wetlands and floodplains, a rich and diverse environment that provided everything they needed for food, shelter, clothing, and trade. The Chinooks were above all a trading people, and they roamed a network of waterways that ranged for hundreds of miles along the coast, inland to Puget Sound, Hood Canal, the Chehalis River, and even on to the plains. The settlement on a quiet feeder of the Columbia was an ideal starting point for the Cathlapotle's goods-laden canoes, hollowed from giant cedar logs.

The first documented visit by a non-Native to Chinook territory was in May 1792 when an American fur trader, Captain Robert Gray (1755-1806), entered the lower Columbia River in his ship Columbia Rediviva. He was followed in October of that same year by British Royal Navy Lieutenant William Broughton (1762-1821), who was exploring the Columbia River under orders from Captain George Vancouver (1758-1798). Broughton made note of a "large Indian village" he encountered, which is now generally considered to have been the Cathlapotle settlement.

Although there were no doubt additional contacts with non-Native traders and trappers arriving by both land and sea, the next well-documented meeting between the Cathlapotle and Westerners came on November 5, 1805, when the Lewis and Clark expedition happened by. The American explorers recorded the meeting in their log:

"Shore by a narrow chanel at 9 miles, I observed on the Chanel which passes on the Stard. Side of this Island a short distance above its lower point is Situated a large village, the front of which occupies nearly 1/4 of a mile fronting the Chanel, and closely connected, I counted 14 houses (Quathlapotle nation) in front here the river widens to about 1-1/2 miles. Seven canoes of Indians came out from this large village to view and trade with us, they appeared orderly and well disposed, they accompanied us a fiew miles and returned back" (Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition).

Lewis and Clark returned to trade and visit further with the Cathlapotle on March 29, 1806, and at that time they estimated the settlement's Native population to be 300 (some secondary sources mistakenly transcribe this number as 900), or about 21 persons for each of the 14 large cedar plankhouses. The expedition's relations with the Indians remained friendly, and the principal chief of the village was honored with the gift of a medal.

These amiable contacts did not foretell the disaster that was to come. Trade between the Chinook and the whites increased over the ensuring years, and although the Natives suffered from scattered outbreaks of "western" illness, it was not until 1828 that a new and devastating disease was carried to the tribe from the outside world. Called the "Cold Sick" by the Indians (the leading contenders are malaria and influenza), this illness, abetted by other imported diseases, nearly eradicated the Chinook Indians within the space of 10 years. By the time the first white settler arrived to stay, in 1839, the remaining Cathlapotle, their population decimated by disease, had largely abandoned the settlement, leaving the land open for homesteading.

A Settlement of One

James Carty (1808-1873), born in County Wexford, Ireland, arrived at the Native settlement site on Lake River in 1839 after an odyssey that took him from his homeland to New York, then around the Horn to the Hawaiian Islands on a whaler, and on by trading ship to Fort Vancouver, where he was briefly employed by the Hudson's Bay Company.

Carty built a log cabin at or very near the site of the Native plankhouses and settled in, with the few surviving Cathlapotle as his only neighbors. It appears from the record that he was unmarried, and remained so. For 10 years after his arrival, Carty apparently had the future townsite almost to himself, sharing it only with a scattering of surviving Natives who, given the toll taken by imported disease, remained remarkably friendly. His nephew, also named James Carty, arrived some 20 years later, and that nephew's son, William, became a prominent Ridgefield citizen and long-serving state legislator.

Alone No More

In 1839, three more bachelors arrived, all of whom were employed in sawmills downstream at St. Helens, in what is now Oregon. These three, Stillman Hendricks, B. O. Teal, and George Thing, built separate cabins on an island in Lake River near Carty's mainland abode. Although often referred to as "Columbia Island" on early maps, it has come to be known as "Bachelor Island" after these three spouseless settlers.

It was not until passage of the Donation Land Claim Act by Congress in 1850 that this small enclave, still known only by the name of its original Native inhabitants, began to slowly develop as a real settlement. Records indicate that several land claims were filed in the early 1850s, including Arthur Quigley's in 1852, Frederick Shobert's (1806-1873) in 1853, Asa Richardson's in 1855, and John Rathbone's (sometimes spelled "Rathbun) in 1867. It is likely that more settlers came to the area in the the 1850s, leaving no paper trail, but real growth was not to occur until later in the century.

A Town by Any Name

With people came commerce. Steamboats labored up and down region's rivers, linking small settlements to markets in Vancouver and Portland. In 1851, James Carty received a permit to run a ferry across the Lake River, and both Quigley and Shobert established crude mud landings on their properties to accommodate the steamers. The settlement came to be known as Shobert's Landing after that family began providing accommodations at their homestead for travelers on the river.

Shobert's Landing continued its slow but steady growth, and in 1865 (at least one source says 1873) the town's first post office was opened in the home of Asa Richardson, who served as postmaster. The progress represented by their own post office occasioned a decision by its citizens to rename the town "Union Ridge." Although the name clearly referred to the Union side of the Civil War, historians disagree as to whether it reflected the general Union sentiments of the citizenry, or was chosen to honor Union veterans who settled in the area in the last year of the war. In an article written in 1875, Vancouver mayor W. Byron Daniels stated that "It was first called Union Ridge during the rebellion, because all the settlers, save one, were outspoken Union men" (Standal, "Ridgefield, Washington: Historic Overview of a Small Northwestern Town"). Neither the identity nor the fate of that sole Confederate supporter is recorded.

A New Generation and a New Name

In 1873 James Carty, who alone had started the settlement that was to become Ridgefield, died in the home he had built nearly 35 years earlier, apparently still a bachelor. He had seen the little town grow from his one rough cabin to an established, if not exactly booming, community, sustained by an economy based largely on agriculture and the timber industry. Within a few years of Carty's death, Stephen Shobert and J. H. Thompson opened the community's first store (1882), and the following year a Presbyterian church, the town's first church of any kind, was built on land donated by the Shobert family. Though no longer a church, this building still stands on Main Avenue in Ridgefield.

In 1885, the attractions of the townsite were rather floridly described in one of the first histories of Clarke (later corrected to "Clark") County:

"There is little doubt that the gently sloping land extending from the elevated highlands down to the banks of Lake river, attracted the notice of many of the very first arrivals in the country and had long been marked as a spot whereon to settle, when that good time should come. Taking a position upon a piece of raised ground near the post office at Union Ridge, one looks upon a panorama unsurpassed for pastoral beauty in any portion of Washington Territory. To the north we see Lake river with the extensive valley lying between it and the rolling Columbia, on whose bosom we notice Bachelors Island, and beyond, the bold bluffs of Cowlitz county, indeed to right and left, in front and back, the scene is beyond description lovely, compassing the fairest dream of sylvan beauty" (History of Clarke County, Washington Territory, 339-340).

Subsequent years saw another name change and gradual further development. In 1890, S. P. Mackey took over as Union Ridge postmaster, and, being from Virginia, he did not like the word "Union" in the town's name. Mackey circulated a petition to change it. The Civil War was long over, and the citizenry agreed that a new name was in order. At a public meeting later that year, the assembled townsfolk settled on the name "Ridgefield." It had taken more than 50 years, but the community that had started out as "Cathlapotle," a name nearly unpronounceable to white settlers, finally got a name that would stick.

And progress continued, although in fits and starts. In 1892 the town's first schoolhouse was built, and in 1893 the first telephone line to Vancouver was strung. There had been hopes that the railroad would reach Ridgefield early in the 1890s, but construction stopped short in 1890, apparently due to financial problems. Even without a railroad, progress was made. Basalt rock quarried from areas around Ridgefield through 1910 was barged to Portland for use as cobble paving stones. The N. C. Hall Creamery, another of the town's first real industries, moved from Vancouver to Ridgefield in 1896, drawn by the abundance of dairy cattle there. A gristmill, furniture factory, and blacksmith shop opened in 1897, and the railroad finally arrived in 1903 (some sources say 1901), linking Kalama, Cowlitz County to Vancouver, Clark County, with a stop at Ridgefield. Vancouver was now less than an hour away, and Ridgefield was freed from its reliance on river steamboats to get its goods to outside markets.

A Temperance Town Incorporates

Businesses were welcome in the young town, but some were more welcome than others. When railroad construction restarted in 1900, a saloon opened in Ridgefield to cater to the work crews, and it was not greeted with enthusiasm. A petition was circulated asking the county commissioners to deny the saloon a license renewal. More than 200 signatures were gathered (which would appear to be nearly the entire population), and the saloon closed its doors after one year. Later efforts to open a saloon in 1906 were unsuccessful, but there is evidence that Ridgefield had a plentiful supply of "prune whiskey" right through the Prohibition years (prunes and potatos were the area's main crops). And in La Center, just six miles away, there were two saloons that happily served all comers, at least until Prohibition.

Perhaps tired of having to appeal to county authorities to control such unwanted activities as saloons, the citizens of Ridgefield voted to incorporate as a city on August 20, 1909. A short time before the incorporation vote, Ridgefield's postmaster, J. W. Blackburn, sang the town's praises in The Coast magazine, writing in part:

" The country surrounding and tributary to Ridgefield cannot be surpassed for fertility and productiveness in the Northwest ... we have soil and climate unsurpassed in the world for all kinds of agricultural pursuits, especially fruit and nut raising, and every year sees more acres of new orchards planted ... . On our bottom lands, which are extensive, are found the finest dairy and stock ranches ... . The writer has spent eleven years in this locality, having seen the bounteous crops and rich harvests, having enjoyed the glorious and health-giv'ng summers and mild winters, having lived in the storm and buzzard centers of the east, the sun-kissed lands of California, the far-famed webfoot Willamette Valley and I now, indeed, think, yea, I should say know, that here I have found the "garden spot" of creation, and Ridgefield is its hub" (The Coast, Vol. 17, No. 4).

Blackburn also provided an inventory of Ridgefield's business community, which provides some measure of how the town had grown over the previous 10 or 12 years. In addition to the N. C. Hall Creamery, Blackburn cited the F. E. Passmore & Sons Shipyard, recently relocated from Lynn, Massachusetts; two poultry yards; three general merchandise stores; two blacksmith shops; a meat market, a livery stable, a barber shop, and a shoe shop; two hotels; a picture-framing shop and a cabinet shop; real-estate offices; and a "temporarily idle" flour mill. He noted that "the Ridgefield Commercial Club has just been organized, and with the spirit prevailing over the entire Northwest is putting forth every legitimate effort to bring capital to our town and establish a manufacturing center." These businesses provided goods, services, and employment for the town's population of 297, as measured by the 1910 federal census. And, on October 8, 1909, the first edition of a town newspaper, the Ridgefield Reflector, was published.

Factories and Fires

Blackburn's hopes for Ridgefield were soon realized. The town's first doctor, R. S. Stryker, opened an office in 1910. The Ridgefield State Bank, the town's first, opened in February of that year, and in January 1911 a new eight-room schoolhouse was built. In 1913, John Bratlie and Walter McClellan opened a shingle mill (later to be called the Bratlie Brothers Mill), which by 1920 was employing nearly 100 workers out of a total population of 620.

Shingle mills, operated by several different companies, were to become Ridgefield's primary industry until 1957, when the last one went bankrupt. Electricity came to Ridgefield in 1916, when the Bratlies extended their lines from the mill to the young city, paving the way for the formation of the Ridgefield Light and Power Company. Also in 1916, the steamship City of Ridgefield was launched and began a regular run to Portland.

The town's progress was not without setbacks, however, and fires seemed to be a particular problem in the first half of the twentieth century. Major blazes occurred in 1916, 1923, 1927, 1934, and 1943. The 1916 fire destroyed much of Ridgefield's business district, and in 1943 alone there were three shingle-mill fires. The two decades between 1920 and 1940 also saw very slow population growth, with a gain of only 23 residents over the 20-year period.

Weathering Depression and War

Perhaps due in part to this stable population, Ridgefield was not a bad place to be during the Great Depression. There was farming and fishing, and the mills operated when they could. There was even a communal "Poor Farm" where destitute families could live and at least subsist, growing most of their food. All in all, the people of Ridgefield got by better than most.

The Depression was followed by World War II, and Ridgefield's citizens did their part, including six of the eight sons of Floyd Patten (1889-1945) and Anna Billotte Patten (1888-1927). All six were serving together on the U.S.S. Nevada when it was attacked at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The ship was saved only when the skipper intentionally ran her aground. All six Patten boys survived and were later assigned together to the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Lexington. During the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, Japanese aircraft severely damages the Lexington, and all hands were ordered to abandon ship. Again, the six "Battling Pattens" survived unharmed. After that, each was assigned to a different ship, and all made it through the war alive.

The Post-War Years

Immediately after the war, L. S. “Sam” Shoen (1916-1999) and his wife, Anna Mary Carty Schoen (of the pioneering Carty family), frustrated by their inability to rent a trailer for a move from California to the Pacific Northwest, started the U-Haul Company on the Carty ranch in Ridgefield in 1946. It was the first company to provide short-term rental of trailers that could be picked up in one state and left in another, and it went on to dominate the truck and trailer rental business for decades.

The 1940s appear to have been a time of optimism and determination in Ridgefield. The little city had survived the Depression, the war, and every other trial that a long history had put in its path. Civic pride in what had been accomplished was evident in a publication celebrating the 40th anniversary of the town's incorporation:

“All the citizens of Ridgefield are confident that the same spirit of progress as exemplified by these early settlers in the laying of the foundation of the Town of Ridgefield will be carried forward and onward by the present citizens in the constructions and future building of the Town of Ridgefield” (Standal, "Ridgefield, Washington: Historic Overview of a Small Northwestern Town").

The Port of Ridgefield

A significant portion of the city's growth in the post-war years, and especially in the later decades of the twentieth century, can be credited to the Port of Ridgefield, established by the voters in 1940 to encourage economic development in the city and surrounding community.

One such effort involved the Pacific Wood Treating Company, which opened a plant on 40 acres of the Port's Lake River Industrial site, providing the city with several hundred jobs. There was a steep price to be paid, however, and when the company filed for bankruptcy and closed its doors in 1993 it left behind a severely contaminated site. Cleanup and remediation began in 1995 but is not expected to be completed until 2014.

The Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge

On the brighter side of environmental protection, the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge was created by Congress in 1965 as a rather unexpected consequence of the great Alaska earthquake of the previous year. The quake had devastated the northern nesting grounds of the dusky Canada goose, and the refuge, along with three other refuges in the Willamette Valley, was created to preserve the natural Columbia River floodplain and to ensure that the geese had secure wintering areas. The refuge consists of four units, which together are known as the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge Complex, with headquarters in the city of Ridgefield. It covers 5,150 acres of marshes, grasslands, and woodlands that lie between the city and the Columbia to the west. It now provides a seasonal or permanent home to many bird species in addition to Canada geese, including sandhill cranes, a great variety of songbirds, great blue herons, and red-tailed hawks. Black-tailed deer are the largest mammal in the refuge, and sightings of coyote, raccoon, skunk, beaver, river otter, and brush rabbits are not uncommon.

The refuge protects more than just birds and waterways. The original Carty homestead was the first of the four "units" to be incorporated into the refuge, and the site of the Cathlapotle settlement is also preserved. Archaeological investigations started there in 1991 and are continuing. On March 29, 2005, 199 years to the day after Lewis and Clark made their second stop to visit and trade with the Cathlapotle, a full-scale Cathlapotle cedar plankhouse was completed at the site and the doors opened to the public. A joint project of the Chinook Tribe, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, archaeologists, and partners from the Ridgefield community, the plankhouse was built to carefully mirror the traditional design of these dwellings. On March 29, 2006, the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge and the Cathlapotle Plankhouse Project commemorated the bicentennial of Lewis and Clark's second visit to the tribe.

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

The completion of Interstate 5 in the 1960s made Ridgefield more accessible, and the creation of the wildlife refuge drew increasing numbers of tourists, but between 1970 and 1980 Ridgefield's population barely increased, from 1,004 to 1,062. The next decade was a little better, and by 1990 there were 1,332 people in the city. But after that things started to accelerate. Between 1990 and 2000, the city gained 270 new residents and added 2,200 acres through annexation. The next decade saw an additional 815 come to Ridgefield, for a total population of 2,147. Between 2000 and 2009, the city's population exploded, more than doubling, to 4,215. Many of these newcomers live in Ridgefield, but work elsewhere. But they still draw new businesses and professionals to the city, and the Heron Gate, Ridgefield's first office building, opened in July 2006, to help accommodate them.

Ridgefield has also taken care to preserve the physical record of its long history. As of 2010, it boasted six sites on the National Register of Historic places, and four additional listings on the Clark County Heritage Register. Among properties listed are the original home Dr. Stryker (1912), the Shobert House (1905-1907), and the Basalt Cobblestone Quarries District in the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge.

Ridgefield's original incorporation called for a strong-mayor form of government, but the mayor's office was volunteer, and as the city grew the burdens of that office became too great. In 1999 the voters approved by a wide margin a ballot measure that changed city government to the council-manager form, in which the elected council hires a city manager and appoints a volunteer mayor from its own ranks. City government hasn't always run smoothly, however. In 2007 the city agreed to pay a former city manager, George Fox, $247,500. Fox had been fired after allegations of racism were made against him over the dismissal of an African American police officer.

In 2009 Ridgefield celebrated the centennial of its incorporation with an optimistic view of the future. Four years earlier, in 2005, the city council and the city planning commission had issued the "City of Ridgefield Comprehensive Plan." It outlined the city's goals: to become a regional employment center, to provide quality neighborhoods, to protect critical environmental areas, and to carefully manage growth. Balancing these priorities may be a tall order, but the challenges met over the more that 170 years since James Carty first set foot in the Cathlapotle settlement on Lake River suggest that Ridgefield is up to the task.