On July 22, 1912, Judge Cornelius Holgate Hanford (1849-1926), appointed in 1890 as Washington state's first federal district court judge, resigns under pressure during the course of an impeachment investigation conducted in Seattle by members of the U.S. House of Representative's Judiciary Committee. Hanford's troubles started when he revoked the naturalized citizenship of a Tacoma man on the grounds that the man was an admitted Socialist. Widespread outrage over this decision led to charges that Judge Hanford was a drunkard and made corrupt rulings favoring large corporations and influential attorneys of his acquaintance. He resigns after several weeks of hearings and just before scheduled testimony that is believed might implicate powerful interests in the Pacific Northwest. The House drops its investigation after Hanford's resignation, and the former judge will go on to enjoy moderate success as an author.

A Very Early Arrival

Cornelius Holgate Hanford was born in Van Buren County, Iowa, on April 21, 1849, and came to Seattle as a child in 1853, but the history of his family in the Puget Sound country started before the city even existed. In January 1850, two years before the full Denny Party set foot on Alki Point, Hanford's maternal uncle, John C. Holgate (1828-1868), had canoed up to Elliott Bay from Olympia. Several sources credit him with filing the first land claim in what was to become Seattle; this appears unlikely, as the Donation Land Claims Act was not enacted until nine months later. But his letters singing the praises of the area were what drew his sister, Abbie Holgate Hanford (b. 1824), her husband, Edward Hanford (1807-1884), and their children, including 4-year-old Cornelius, to the Northwest.

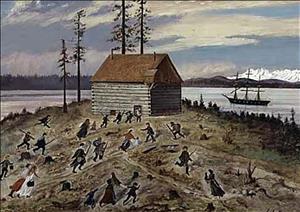

Young Hanford's early years were full of excitement and hardship in equal measure. Along with other settlers, as a 6-year-old he took shelter in a blockhouse during the Indian attacks of January 1856 and later was whisked to safety aboard the U.S. warship Decatur anchored in Elliott Bay. But much of the Hanfords' stock and property were destroyed in the uprising, and the family faced considerable adversity and eventually were forced to sell off their land.

In 1861, when Cornelius was 12, the family moved to California, and while there he worked as an office boy and attended night school. They returned to Seattle in 1866, and Hanford went to work carrying the mail to Puyallup once a week on horseback. In 1869 he moved on his own to Walla Walla, where he did farm work and attended teaching school for three years. When he returned to Seattle in 1872, he decided to read the law and was taken on as a law clerk by George M. McConaha, a prominent Seattle attorney. Hanford was admitted to the bar in February 1875, went into early partnerships with several prominent Seattle lawyers, and embarked on a long and distinguished legal career, only to have it end in disgrace many years later.

Success and Controversy

By most contemporary accounts, Hanford had a quick and analytical mind, which soon won him success in the courtroom. While still in his first year of practice he was appointed U.S. Commissioner for Washington Territory, an office that served as the federal representative in those areas of the nation that had not yet attained statehood. The following year, 1876, he was elected to the Territorial Council (Senate), but served only one term before returning to private practice.

For the next several years the arc of Hanford's legal career soared steadily upward. He was very successful in his law practice, and he served in both elective and appointive public offices. In 1882, 1884, and 1885 he was elected Seattle city attorney, a post that he occupied while also serving as an assistant United States attorney for the Territory. His career seemed to have reached a satisfying zenith in March 1889 when President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) appointed him chief justice for Washington Territory. In fact it was barely beginning, and more honors were to come.

Hanford's term as Territorial chief justice ended in November 1889 when the Territory became a state, but his judicial career carried on without interruption. No sooner had one judgeship dissolved than another was created, and Hanford moved seamlessly from the Territorial bench to the federal bench when President Harrison, on February 25, 1890, tapped him to be the first (and, for the next 15 years, only) federal judge for the new Washington district of the Ninth Circuit. This was a lifetime appointment, and indeed it was where Hanford would spend the rest of his days on the bench. It was also the forum in which he handed down a few decisions that would, in 1912, contribute to the sad and disappointing end of his judicial career.

During his years in private practice, Hanford had both represented and befriended many powerful men in the Pacific Northwest, and he had as clients several of the region's largest corporations, including private utilities and railroads. He was by disposition a free-market Republican, and both his client list and many of his judicial decisions reflected this inclination. This led many to question his fairness, even before the controversy erupted that was to lead to his resignation in 1912. In fact, the previous year, after Hanford had issued an injunction in favor of a street-car company and against the public in a dispute over fare increases, he was vilified at a public meeting, resolutions calling for his impeachment were adopted, and he was hung in effigy outside the courthouse.

The United States vs. Leonard Olsson

During the more than 20 years that Hanford was judge for the Washington federal district court, it is estimated that he issued more decisions than any other judge in the country. He had courtrooms in Seattle, Tacoma, Spokane, and Walla Walla, and over the years he produced nearly 450 published opinions and more than 500 unpublished memorandum opinions. With such a huge volume controversy was inevitable, but it was not until Hanford heard a case brought against an immigrant named Leonard Olsson that the judge's days on the bench became numbered and few.

Olsson (the spelling used in court documents; newspapers of the day seemed to have had a great deal of difficulty with Olsson's name, and it also appears as Olson, Olsen, Oleson, and Olssen) was a Scandinavian immigrant, an avowed Socialist, and a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). He was also an American citizen, having been naturalized on January 10, 1910. Olsson later had the bad grace, in the view of the federal government, to espouse his Socialist views at public meetings. He was accused of "advocating a propaganda for radical change in the institutions of the country ..." thus proving, or so it was alleged, that he had "fraudulently" obtained his naturalization by lying to the court that had administered his oath of citizenship (United States v. Olsson, 196 F. 563, at 564).

The government sued to revoke Olsson's naturalization, and as Judge Hanford was the federal district court judge for Western Washington, the matter ended up in his court. Thus did a son of pioneers, a man who had taken full advantage of the opportunities America had given him, come to sit in judgment of a recent immigrant who held views that were widely regarded as not only erroneous, but imminently dangerous to the American way of life. It was a mismatch from the start.

Judge Hanford had an uncomplicated view of the matter, which he couched in terms of simple fraud, avoiding all mention of the First Amendment free-speech rights that were clearly implicated by the facts of the case:

"The nation generously and cordially admits to its citizenship aliens having the qualifications prescribed by law, but recognizing the principle of natural law, called the law of self-preservation, it restricts the privilege of becoming naturalized to those whose sentiments are compatible with genuine allegiance to the existing government as defined by the oath which they are required to take. Those who believe in and propagate crude theories hostile to the Constitution are barred ... .

[Olsson] has no reverence for the Constitution of the United States, nor intention to support and defend it against its enemies, and he is not well disposed toward the peace and tranquility of the people. His propaganda is to create turmoil and to end in chaos. But in order to secure a certificate of naturalization he intentionally made representations to the court which necessarily deceived the court, or his application for naturalization would have been denied. Therefore, by the petition which he was required to file and his testimony at the final hearing of his application and by taking the oath which was administered to him in open court, he perpetrated a fraud upon the United States and committed an offense for which he may be punished as provided by the law" (United State v. Olsson, 196 F. 563 at 565-566).

Although Judge Hanford included many more conclusory statements about the dangers of Socialism in general and the dishonesty of Olsson in particular, the essence of his holding was simply this: Socialists were against private property; ergo, they were by definition opposed to the Constitution's provisions that protect "life, liberty, and property"; ergo, they could not swear allegiance to that Constitution without committing perjury. Since Olsson admitted to being a Socialist, his perjury was manifest, self-evident, and beyond dispute, and there was only one possible outcome. He should be stripped of the only ill-gotten gain of his alleged fraud -- his U.S. citizenship.

The judge's decision was handed down on May 11, 1912, and within four days the controversy it engendered was being played out in, among many other places, The New York Times. There were dozens of articles and opinions published, some supporting and others castigating the judge, and there were legitimate differences over the legal correctness of his ruling. But the furor caused by the Olsson case was to rekindle complaints about some of Hanford's earlier decisions, decisions that many believed favored corporate interests over those of the public. It was this larger controversy that would ultimately lead to Judge Hanford's downfall and public disgrace.

Under Attack

Legal commentators seemed to agree that Judge Hanford would have been on sound legal ground if he had refused to grant Olsson citizenship in the first place, but were less sure that a judge had the right to revoke a person's citizenship once it had been granted. These fine legal distinctions found little place in the public response, which was largely one of outrage. But Hanford had supporters too, and one of them, The Seattle Times newspaper, hired a leading Seattle law firm to examine the judge's ruling and report to the public on its findings. The opinion was clearly foreordained, and perhaps to put some distance between it and the bought-and-paid-for lawyers, the newspaper chose to print the study's conclusions in The Common Cause, the publishing organ of a national organization of the same name that opposed Socialism in all its aspects. To make sure that no one missed the point, the article was liberally sprinkled with emphatic capital letters:

"The court in the Olsson case did not decide that an alien who had HONESTLY SECURED HIS CERTIFICATE OF NATURALIZATION could thereafter be deprived of his right as a citizen. What the court really decided was that an alien WHO HAD OBTAINED A CERTIFICATE OF NATURALIZATION BY FRAUD AND PERJURY, which had deceived the court granting him a certificate of naturalization, the CERTIFICATE SO OBTAINED should be canceled" (The Common Cause, p. 159).

On the other side of the argument, some of the criticism of the judge was hyperbolic, and the sources predictable. On May 15, 1912, The New York Times quoted Emil Seidel (1864-1947), a former mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (a city and a state that were home to many Socialists):

"The best thing they can do with Judge Hanford is have a Lunacy Commission investigate his case. The idea of Oleson [sic] tearing down the Constitution which he swore to uphold is crazy. How can you or I tear down the Constitution? The asylum is the place for that Judge."

A more commonly help opinion was that expressed by Colonel C. E. S. Wood, of Portland, Oregon, in a weekly magazine published by a prominent Progressive, Robert LaFollette, also of Wisconsin:

"According to Judge Hanford's decision, a man's citizenship may be taken from him simply because his political views do not coincide with those of the judge in the case. It's mighty poor law and mighty dangerous doctrine" (LaFollette's Weekly Magazine, p. 7).

In fact, the state of Wisconsin proved to be the geographical wellspring of Hanford's undoing. It had the distinction of having elected the first acknowledged Socialist to serve in Congress, Representative Victor L. Berger (1860-1929). Berger had a personal and particular interest in protecting one's right to hold political beliefs that were not universally popular, and he went after Judge Hanford with a vengeance. Within weeks, he had enlisted the support of U.S. Attorney General George W. Wickersham (1858-1936), who issued a statement that his department "was of the opinion that a gross injustice has been done to Mr. Oleson [sic] in cancelling his certificate of naturalization" (The New York Times, June 6, 1912).

Armed with the statement of the attorney general and with damning information that had been gathered from Hanford's many detractors in Washington state, Berger on June 7, 1912, stood in the well of the House of Representatives and called for impeachment proceedings against the judge. He accused Hanford of "high crimes and misdemeanors," of being "an habitual drunkard," and of having issued "a long series of corrupt and unlawful decisions." It was apparent that his colleagues in the House, whatever their political beliefs, did not need much persuading. Within a week, the House by a unanimous vote directed the Judiciary Committee to start an impeachment investigation against Judge Hanford, and a three-member subcommittee was dispatched to Seattle to conduct the inquiry.

Judging the Judge

The investigators opened their hearings in Seattle on June 27, 1912, hampered by the fact that there was no transcript of Olsson's original hearing and Judge Hanford claimed, somewhat implausibly, to have kept no minutes or notes on the case. The first witness called was Mr. Olsson himself. While not in the least repentant, he did not come across as a dangerous revolutionary. He testified that Judge Hanford had asked him if he was "devotedly attached to the Constitution of the United State," and that he had replied by saying that although he had no "superstitious reverence for the document," he was willing "to abide by the laws of the country" (The New York Times, June 27, 1912).

After Olsson's testimony, the hearings appear to have taken on a somewhat farcical air. Witnesses were called who testified that they had observed Judge Hanford drunk in the bars, drunk in the streets, drunk in the streetcars, and drunk (and asleep) in the courtroom. His supporters responded somewhat weakly that they had never seen him in those places in that condition, and that perhaps it was just that the judge's "peculiarities and mannerisms had been misunderstood" (The New York Times, July 23, 1912).

But this was all sideshow -- the blow that Judge Hanford would not survive came from another quarter. It fell on July 20 when the committee released documentary evidence showing that the Northern Pacific Railroad, at the direct command of its president, had sold land to the judge on very favorable terms shortly after Hanford had rendered a decision that saved the company more than $60,000 in taxes. The fact that this decision was overturned on appeal was not viewed as exculpatory, and the investigating committee hinted broadly that more, and worse, revelations were soon to come.

After this, rumors abounded that other large corporations and their white-shoe attorneys were going to be served up next by the investigators. There were tales told of late-night meetings between Hanford and powerful men who could be adversely affected by further inquiries. The truth of these stories was never established, but it is a fact that on July 22, 1912, before the committee could reconvene, Judge Cornelius Holgate Hanford, a proud man with 23 years on the bench, rather meekly resigned. His resignation was accepted by President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) two weeks later, on August 5.

Out, But Not Quite All the Way Down

It was widely believed that Hanford had stepped down under pressure from railroad interests and prominent corporate attorneys who had reason to fear what further hearings might reveal. True or not, after his letter of resignation was received the inquiry was quickly stopped. One commentator at the time said:

"There is no need to impeach him to prevent his holding future public office because his age and the circumstances disclosed by the testimony render such a contingency highly improbable" (When Courts and Congress Collide, 167).

For his part, the judge issued a public statement that was a mixture of reminiscence and bluster, and said in part:

"I am grateful for the commendation of those who have spoken and written in my favor — and as for those who have maligned me, I only wish to say that I would be ashamed of myself if I had not incurred the enmity of such people as they are.

A judge is never so sure of being right as when his work has been criticized unfairly. Without boasting, and in view of all that has been and may be said of and concerning myself and my work, I am glad that my record is what it is" (The New York Times, July 22, 1912).

Judge Hanford's days in the public eye were not quite over, however, and he was to achieve a measure of further recognition, if not redemption, as an author. In 1917 he penned a novel entitled General Claxton, and his three-volume Seattle and Environs, 1852-1924 is considered a useful work on the city's early history. But his professional reputation as a lawyer and judge were irretrievable.

And what of Leonard Olsson? On June 5, 1912, weeks before the impeachment investigation began, Attorney General Wickersham ordered the U.S. Attorney in Seattle to reopen the case. On June 19, Hanford denied Olsson's motion for a new trial, despite the fact that the federal prosecutor did not oppose it and in fact agreed that it was necessary.

The next mention of Olsson in the press was on September 12, 1912, when the Bellingham Herald reported, under the somewhat misleading headline "Olsson to Get Citizenship," that:

"The United States Attorney will file a stipulation [in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals] which practically will be a confession of error. This is expected to cause the circuit court to restore Olsson's citizenship."

However, on February 14, 1913, The New York Times reported that the Court of Appeals, pursuant to an agreement reached between prosecutors and Olsson's attorneys, had ordered a new hearing in his case, but had not restored Olsson's citizenship. Given the outcome of the investigation into Judge Hanford's conduct and the government's admission of error, it seems highly likely that Olsson fully prevailed in the end, but this author has been unable to find anything of record to establish that as fact.

On November 26, 1915, in Tacoma, a man named Leonard Olsson, with the same unusual spelling of the last name, died at the age of 38. If this was indeed the Leonard Olsson who had done battle with Judge Hanford, he did not long enjoy the satisfaction of his considerable victory.