Coupeville is one of Washington's oldest towns and the seat of Island County. Situated on Whidbey Island, at Penn Cove on Saratoga Passage, the town was once the site of three permanent Lower Skagit tribal villages. Named for pioneer Thomas Coupe, it was settled by sea captains and farmers in the 1850s. Whidbey Island narrows near Coupeville; nearby Ebey's Landing and Ebey's Prairie share a common history. The activation of Fort Casey in 1901 spurred efforts for Coupeville incorporation in April 1910. During the Great Depression, Whidbey Island utilized government funds for building projects such as Deception Pass Bridge (1935). Many of Coupeville's older structures survived into the 1970s and Whidbey Island support for the arts and tourism gave impetus to formation of Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve, the first of its kind recognized in the U.S. Continued support of tourism has preserved four blockhouses, historic buildings, and homes, and most significant, the prairie itself. Gift shops, restaurants, businesses, and boutiques in heritage buildings now line Coupeville’s Front Street and the Island County Historical Museum on Main Street interprets Whidbey Island’s past.

Natives and Explorers

Penn Cove was once home to Lower Skagit tribes who built three permanent villages at this location, the largest being bah-TSAHD-ah-lee (snake place), now present-day Coupeville. The protected harbor, facing Saratoga Passage, offered abundant salmon, clams, mussels, flounder, sole, and cockles, as well as easy access to nearby waterways and inland forests. An old Native burial site was located on the cove.

British Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798) made journal entries of his visit to the island in the summer of 1792. He named it in honor of Joseph Whidbey (1755-1833), master of the HMS Discovery, and Penn Cove in remembrance of a friend. The Native word for the island was Tscha-kole-chy. Vancouver met a small number of Skagits and wrote that their tribes had once flourished but had been decimated by disease.

In 1848 Whidbey Island’s first non-Native settler, Thomas Glasgow, filed a land claim on what is now Ebey’s Prairie. Glasgow married Chief Patkanim’s daughter Julia, who served as a translator. After journeying to Olympia to file a land claim, Glasgow returned to the Island and found 8,000 members of various tribes assembled at Penn Cove to discuss the incursion of whites into their traditional hunting and fishing grounds. Julia feared Glasgow’s life was threatened and the couple left for Olympia, where they legally married and did not return to the island. Following the Point Elliott Treaty in 1855, many of the Lower Skagit people were placed on the Tulalip reservation. A few continued to live in Coupeville.

Donation Land Claim Settlers

The same Whidbey Island locations that appealed to the Skagits also appealed to early sea captains and non-Natie farmers who explored and settled central Whidbey Island in the early 1850s. Ebey’s Landing, on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, was an easy place to reach by water, and the nearby prairie and protected harbor of Penn Cove made excellent sites for establishing homes and farms.

On September 27, 1850, Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act, granting free land (320 acres to single men and 640 acres to married couples) to anyone who had settled on the land before December 1 of that year. Colonel Isaac Neff Ebey (1818-1857) was the first man in Central Whidbey Island to file a claim (640 acres) on October 15, 1850. During the years of the Donation Land Claim Act, updated in 1853 and again in 1854, 29 settlers registered claims on the Prairie and Penn Cove.

A small settlement called Coveland formed at the head of Penn Cove and served as the first Island County seat (1853-1881). Captain Benjamin Barstow (d. 1854) opened the first trading post at this location in 1853. A group of land developers platted Coveland in 1888 and changed the name to San de Fuca, chosen because of its proximity to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. From 1881 to the present time, Coupeville has been the Island County seat.

While Whidbey’s sea captains conducted coastal trading, most of the settlers were drawn to the island’s rich prairie land. Here they farmed, planted and sold wheat, oats, barley, fruit, and potatoes, and even raised sheep. Settlers soon found that logging was their best cash crop. Using primitive tools, they began cutting the forest. It took the changes in logging technology that would come in the twentieth century to enable the massive removal and marketing of most of Whidbey’s trees.

The government’s intention in granting free public land was to encourage settlement in the region and claimants were required to "develop and improve" their land, which usually included clearing away trees. Settlers took profit from small harvesting, but large logging and milling operations -- able to quickly clear land -- made money from the timber they sold. The U.S. government allowed these operations to log and pay a small fee for each tree cut, but the companies greatly profited and much public land quickly fell into private ownership. The forests on Whidbey Island were routinely cut by Puget Mill Company as wells as by mills at Port Blakely, Port Ludlow, and Utsalady (Camano Island).

John Sprague, head of the western division of the Northern Pacific Railroad, purchased 20,000 acres of land in Island County, launching rumors that the Northern Pacific would establish its West Coast terminus at Coupeville. But the Northern Pacific chose Tacoma instead and profited from logging and real estate at Coupeville.

Thomas Coupe (1818-1875)

Coupeville was named for sea captain Thomas Coupe, who arrived on Puget Sound on the bark Success. Scouting the area, Coupe settled at Penn Cove in 1852. His wife, Maria, and their family joined him there in 1853 and Captain Coupe worked as a coastal trader, sailing both the Success and the Jeff Davis, the first revenue cutter on Puget Sound (part of the armed maritime law enforcement service). He also built and operated a number of small schooners as well as a steamer that he also named Success. The Coupes did not initially file for their property and settler C. H. Ivans claimed the same piece of land. On April 3, 1854 Coupe filed his claim and eventually paid Ivans to clear the title. It was not until September 1865 that Coupe was granted the property, the west half assigned to him and the east 160 acres to Maria.

The Coupe and Alexander properties on Penn Cove eventually comprised the town of Coupeville.

Isaac Ebey: His Life and Death

Indian unrest following the Point Elliott Treaty signing in January 1855 led Whidbey settlers to build four blockhouses for protection. Colonel Isaac Ebey had taken the earliest Donation Land Claim near Ebey’s Landing and in 1852 served as a representative from Thurston County in the Oregon Territory Legislative Assembly. During his time of political service, Ebey helped to form Island, Jefferson, Pierce, and King counties. In 1853, Ebey was appointed as Island County’s first Justice of the Peace and also served as a probate judge. This same year, President Franklin Pierce (1804-1869) appointed Ebey as Collector of Customs for the Puget Sound District. Ebey promptly moved the Customs House from Olympia to Port Townsend. During the Indian Wars (1855-1856), he commanded a company of Washington Territorial Volunteers.

On August 11, 1857, Ebey was shot and beheaded at his home on Whidbey Island by southeast Alaskan Kake (Tlingit) Indians in retaliation for the murder of 27 Kake tribal members during relocation talks aboard the U.S. Navy steamer Massachusetts the previous year. Ebey’s murder spurred residents to build three more blockhouses. Four of these seven remain, and over the years have been rebuilt and restored.

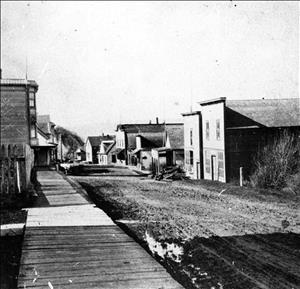

Early Coupeville Development

In 1881 Coupeville became the Island County seat and began to look like a real town, with an increasing number of homes, stores and churches. Water routes were the main avenues of transportation until 1900 and their efficiency actually slowed the progress of road development. "Mosquito Fleet" steamers operated out of Coupeville, running to Bellingham in the 1890s. The town prospered from shipbuilding, and from shipping fish, produce, lumber, and timber.

Thomas A. Cranney (1859-1919) and Lawrence Grennan operated a general store at Coveland as early as 1856. The building became the first Island County courthouse and Grennan and Cranney began to market lumber and timber, operating a mill in Utsalady on Camano Island.

In 1906, Coupeville resident Howard B. Lovejoy (1859-1919) purchased the sternwheeler Fairhaven and began runs between Penn Cove and Seattle, stopping at points on South Whidbey Island. By 1911 Lovejoy expanded his ferry service and with his family and partners James Esary and the Byers brothers, founded the Island Transportation Company, adding the steamers Atlanta, Clatawa, Calista, and Camano, and a new run to Port Townsend. Lovejoy’s company merged with the Sound Ferry Line, becoming the Whidbey Island Transportation Company.

Coupeville Incorporation

By 1900 Coupeville’s population was around 300 but the opening of Fort Casey in 1901 quickly added a floating population of more than 300 men to Central Whidbey, and residents began pushing for town incorporation. Coupeville needed better roads, utilities, dock improvements and city fire and police services.

In February 1910 the Island County Board of Commissioners called for a vote on Coupeville incorporation and town boundaries were accepted according to a filed plat of Coupeville. Thomas and Maria Coupe’s property formed the eastern portion of the town, with John Alexander’s property making up the western portion.

Not all residents were supportive of city incorporation, many expecting the loss of good island farmland and a rise in taxes, but on April 2, 1910, Coupeville residents voted 41 to 36 in favor of incorporation and approved a roster of candidates. Charles H. Lyon (b. 1862) was elected mayor with J. Straub, A. D. Hallock, Albert R. Kineth, Edwin O. Lovejoy, and H. W. Libbey elected to the city council. Articles of Incorporation were filed with Island County commissioners on April 4, 1910, and recorded with the state of Washington on April 13.

Fort Casey, Fort Ebey, and the Naval Air Station

Whidbey Island has long been a key defense site and military relics have survived from several eras. Today’s Naval Air Station at Oak Harbor employs more than 80 percent of the island’s population.

Two U. S. military sites -- Fort Casey and Fort Ebey -- have long island histories. Earliest built was Fort Casey, three miles south and west of Coupeville, on Admiralty Head. Established in the 1890s as the third in the protective triangle of forts guarding the Pacific Northwest, Fort Casey was armed with giant guns and bunkers. It was activated in 1901, bringing more than 300 men to Central Whidbey. Fort Casey is also home of the 1903 Admiralty Head Lighthouse.

Immediately west of Coupeville is Fort Ebey, built by the Harbor Defense Command during World War II (1941-1945) to help protect military bases around Puget Sound against attacks by the Japanese Imperial Navy. Along with gun emplacements, it was also an important RADAR site.

Coupeville's Great Depression

The hard times of the Great Depression helped turn Whidbey Island’s commerce toward tourism. Coupeville took advantage of federal funds under the National Recovery Act (NRA), the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) to further road building and repairs, to extend the town’s water system and to build its first sewage treatment plant.

But the largest Whidbey Island project was the building of the Deception Pass Bridge, completed in July 1935, connecting Whidbey and Fidalgo Islands. The new bridge now made an easy connection from the mainland to Whidbey. Auto travel became popular and the creation of Deception Pass State Park in the 1930s soon made it a national tourist destination. The Deception Pass Bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

Building Tourism

Explosive growth in the 1950s and 1960s threatened the rural lifestyle of Whidbey and island residents needed to make choices. Increasingly more dependent on the Naval Air Station at Oak Harbor for jobs, residents also saw plans by large development corporations for multi-family structures and housing additions. Between 1953 and 1979 Coupeville annexed 11 times, bringing the town size to nearly 700 acres.

A bridge from Mukilteo to Clinton was in the works in the 1960s but the Boeing recession of the late 1960s and early 1970s killed these plans and gave islanders a chance to reconsider their future. Island dwellers opted to maintain their quiet rural life and, along with other towns, Coupeville encouraged single-family homes, small businesses, and tourism.

A boom of bed-and-breakfast lodging establishments, gift shops, and arts functions blend well with Whidbey’s strong heritage focus and have added to the island economy since that time. Old buildings along Coupeville's Front Street have been maintained, although businesses in them have changed to accommodate tourists, with a greater number of restaurants and gift shops. A movement began in the 1970s to save Ebey's Prairie.

Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve

Approximately 8,000 acres of Central Whidbey Island, including the town of Coupeville, was designated the Central Whidbey Island Historic District by Island County commissioners in 1972. and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. In 1978 the district was made part of Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve -- the first of its kind in the nation -- to preserve and protect a natural landscape and rural community, thus providing a continuous historic record from the eighteenth century to the present time.

The reserve is managed by a local trust board representing the town of Coupeville, Island County, Washington State Parks, and the National Park Service, and 85 percent of the property remains privately owned. A map of a 2.5-mile walking tour of the Historic District is available online.

Coupeville and Central Whidbey Today

The largest area of remaining forest land near Coupeville today is found in Fort Ebey State Park, on 645 acres, with three miles of saltwater shoreline on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The park offers some two dozen miles of hiking and mountain biking trails as well as fishing, beachcombing, birdwatching, and paragliding. The Fort Ebey site was acquired by Washington state in 1968 and became Fort Ebey State Park in 1981.

Deactivated by the government in 1953 and scheduled for disposal, Fort Casey was acquired in 1955 by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and 100 acres of Fort Casey’s battery area is now a state park and historical monument. Seattle Pacific University purchased 87 acres, including most of the fort’s administrative buildings and housing to create the Camp Casey Conference Center. The present Fort Casey State Park, including the Keystone Spit area, was acquired between 1955 and 1988 in three parcels, at a total cost of $300,000. Fort Casey is home to the Admiralty Head Lighthouse, built in 1903.

Four Central Whidbey Island blockhouses remain, originally built to guard against Native American attack during the Indian wars of 1855-1857.

1. The 1855 Alexander blockhouse. Moved from the John Alexander farm to its present location next to the Island County Historical Museum on Main Street in Coupeville.

2. The 1855 Crockett Blockhouse. One of two stockaded blockhouses, moved to just southwest of its original site. (The other one was moved to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909). Located on Fort Casey and Crockett Farm Road intersection.

3. The 1857 Davis blockhouse. Restored by the local Ladies of the Round Table and dedicated by Professor Edmond Meany in 1921 and again restored in 2007 by the Island County Cemetery District and the Coupeville Lions Club. Stands in Sunnyside Cemetery on Sherman Road, Coupeville

4. The 1857 Ebey Blockhouse. One of the four stockade blockhouses protecting the Jacob Ebey house. On Ebey’s Bluff.

Other establishments at Coupeville include Whidbey General Hospital, a nonprofit public district hospital dedicated on March 9, 1970; the Pacific Northwest Arts School (1986), known for its visual arts workshops, art expeditions, conferences, and forums; the Penn Cove Shellfish Company (1975), which provided sustainably farmed shellfish. Coupeville hosts the Penn Cove Mussel Festival and the Penn Cove Water Festival, and the Island County Historical Society maintains a museum and small research library where staff and volunteers help preserve and interpret Island County history.