There were no fewer than four outposts named Fort Walla Walla, but the last and most enduring was established as a cavalry post on March 18, 1858. This military reservation housed soldiers who would fight in the Pacific Northwest Indian Wars and help to bring law and order to early communities of settlers, but the fort and the army were disgraced in April 1891 when soldiers stationed there shot and killed a local gambler in Walla Walla. During its first 40 years repeated efforts to close the fort were rebuffed, but in 1910 it finally was shut down. In the 1920s it became a veteran’s hospital. Since then its use has changed to meet new needs. The facility was renamed in 1996 as the Jonathan M. Wainwright Memorial VA Medical Center to honor a famous World War II general and hero who was born at the fort in 1883.

Four Forts, One Name

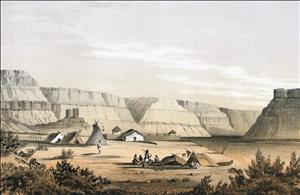

On March 18, 1858, Lieutenant Colonel Edward J. Steptoe (1815-1865) and his men moved into Fort Walla Walla, just east of the town of that name. This was not the first Fort Walla Walla, however. In July 1818 the North West Company opened a fur-trading post at the confluence of the Columbia and Walla Walla rivers. Originally called Fort Nez Perces, it was renamed Fort Walla Walla when the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company merged in 1821. In October 1841, the wooden buildings at the post burned down and were rebuilt with adobe construction. Indian hostility forced the abandonment of this first Fort Walla Walla in 1855, and in 1862 the town of Wallula was built on the site and became an important steamboat landing for travelers to the Idaho and Montana gold fields. The construction of McNary Dam in the 1950s elevated Lake Wallula and submerged the town, which was relocated to higher ground.

In December 1855 the Ninth Regiment was ordered to the Pacific Northwest to protect settlers and bring law and order. Arriving in January 1856, the regiment was divided among various posts, with companies going to Fort Vancouver, Fort Steilacoom, Fort Walla Walla, and headquarters at Fort Dalles, Oregon, under the command of Colonel George Wright (1803-1865). Additional troops, dragoons (cavalry), arrived to bolster fighting capacity.

The second Fort Walla Walla, and the first military post of that name, was established by Lieutenant Colonel Steptoe in October 1856 at Mill Creek, seven miles east of what is today downtown Walla Walla. This post was active for barely one month and closed before the year was out. The army then built a third Fort Walla Walla, located in what later would become part of the city's downtown, near today's 1st and Main streets. This facility included barracks, officers' quarters, and stables. No trace of it survives.

The fourth Fort Walla Walla was built in 1857-1858 and opened as a cavalry post on March 18, 1858. Located about one-and-one-half miles from present-day downtown Walla Walla, it would growto become a 640-acre reservation, which, by the end of the nineteenth century, held 60 buildings. Despite multiple attempts over the years to close the facility, it survives today as the Jonathan Wainwright Memorial VA Medical Center.

The Battle of Tohotonimme (Pine Creek)

On May 6, 1858, Colonel Steptoe left Fort Walla Walla with a force of 159 troops and Indian scouts on a mission into the Indian lands of the Columbia Plateau. The force included Company C, First Dragoons, and Company E, Ninth Infantry. They headed to the area around Fort Colvile (a Hudson's Bay Company post), where two miners had been killed and settlers were worried about their security. Steptoe, a West Point graduate, was an experienced combat officer who had fought the Seminole Indians and served in the Mexican-American War. He had carefully organized his forces for the foray and had brought along two mountain howitzers, but he did not expect any trouble.

On May 15 Steptoe and his troops camped near the present-day town of Rosalia. The next day, as they moved forward, Indians questioned their intentions, noting that the soldiers were traveling east of their normal route and were equipped with artillery. They refused Steptoe's request for boats to cross the Spokane River and began to harass his troops. Steptoe turned around to return to Walla Walla, but on May 17 at Pine Creek a battle began, and 800 to 1,000 Coeur D’Alene, Palouse, Spokane, Cayuse, and Yakama Indians attacked. Colonel Steptoe and his men put up a good fight but were badly outnumbered. That night the soldiers escaped (or were allowed to escape) and made their way back to Fort Walla Walla, reaching the post on May 22. They had lost seven killed -- two officers, four enlisted men, and one Indian scout. The number of Indian warriors who died in the battle is unknown.

Army Colonel George Wright responded to this defeat by launching a punitive expedition from his base at Fort Dalles, Oregon. In August and September 1858, Wright and 600 troops fought the Indians who had routed Steptoe's force. During these battles, Wright's troops rounded up 800 to 900 Palouse horses and killed most of them to deny the tribes the hunting capability that horses provided. This infamous animal slaughter demoralized the Indians, who surrendered shortly thereafter. Colonel Wright ordered some Native leaders hanged, including the Yakama tribal chief, Qaulchan, who went to the gallows on September 24, 1858.

A Narrow Escape

In 1861 the Ninth Regiment and First Cavalry Troops (as the dragoons were now renamed) went east to fight in the Civil War, leaving Fort Walla Walla temporarily vacant. In June 1862 components of a volunteer force, companies A to F of the Ninth Oregon Cavalry, arrived at the fort. The volunteers had three-year enlistments and upon completion of their service were to receive a $100 bonus and 160 acres of land.

The following year, in July 1862, the Ninth Washington Territory Volunteers arrived at Fort Walla Walla and its companies A and B would serve there until the spring of 1865. Once the Oregon volunteer cavalry departed in 1866, the fort served as a depot and was used for wintering animals. Its closure was considered in Washington, D.C., and in February 1871 a congressional bill called for it to be closed and the property sold off as 40-acre lots. However, the bill incorrectly identified the fort as being located in Oregon, and this mistake rendered the law void.

A Fort Reborn

Fort Walla Walla won a new lease on life in 1873 when four First Cavalry Troops and two companies of the 21st Infantry arrived at the fort after serving in the Modoc War in Oregon and Northern California. Their first duties at the fort were to repair buildings and clean up the post. With nearly 300 soldiers, Fort Walla Walla went from near oblivion to become the largest post in Washington Territory by 1880. These garrison troops would depart for Nebraska in 1884.

The Fort Walla Walla cemetery was established in 1856 and interred there, among others, were many soldiers killed in the Indian Wars. These included men from Fort Lapwei in Idaho who died during the battle at White Bird Canyon in June 1877. Michael McCarthy (1845-1914), who joined the Washington Territorial Militia (later Washington National Guard), was awarded the Medal of Honor for gallantry at that battle. He later reached the rank of colonel and settled in Walla Walla, where he headed an effort to raise money to erect a monument to members of the First Cavalry killed in action at White Bird Canyon. Another monument at the cemetery honors First Cavalry troops killed in action at Cottonwood Canyon, Idaho, on July 3, 1877.

Fort Walla Walla always lacked sufficient space to be an effective cavalry or infantry post, and only limited new construction occurred over its history. In 1877 the commanding officer’s house was built, and barracks were constructed in 1883, 1888, 1894, and from 1904-1906. Elements of the Fourth Cavalry, which had captured Geronimo in 1886, came to the fort in 1890, and its Troops D and H were based there until being sent to the Philippines in June 1898. The Fourth had the longest stay of any unit at the post. The Second Cavalry, which replaced it, stayed for only one year, to be followed by the Sixth Cavalry for a short tour. These troops succeeded in controlling the area and protecting the local populace.

Soldiers Slay a Local Citizen

On April 22, 1891, Private Emit L. Miller (1866-1891) of the Fourth Cavalry spent the evening playing cards at Rose’s Saloon in Walla Walla. A local gambler at the same table, A. J. Hunt (1836-1891), ridiculed the First Cavalry. Miller took offense and may have hit Hunt, who pulled out a gun and shot him. Miller was taken to the post hospital in critical condition, while Hunt was quickly arrested and jailed.

The following day, Sheriff J. M. McFarland (1844-1899) took Hunt to Miller’s bedside to be identified as the shooter. His carriage driver waited outside and heard soldiers making plans to attack Hunt. The driver warned the sheriff, who appealed to the post commander, Colonel Charles E. Compton (1836-1909), for an escort. Colonel Compton ordered the officer of the day, Captain Theodore J. Wint (1845-1907) to take five guards to protect the sheriff’s party. When the escorts arrived at the gate, a group of about 75 soldiers threatened them and ignored Captain Wint’s orders to disperse. Realizing they were outnumbered, Wint's party dashed back to the guard house to get a larger force of 25 soldiers, which then escorted the sheriff and his prisoner safely to the town jail.

The next day soldiers were seen hanging around the jail, and the sheriff heard rumors that they planned to attack. That evening McFarland went to Colonel Compton’s quarters and requested that he restrict all soldiers to the fort. Colonel Compton replied he could do nothing and that he did not expect any trouble. Sheriff McFarland returned to the jail and added five or six armed deputies as extra guards. At about nine p.m., 50 soldiers (25 taking positions around the jail and 25 storming the building) overpowered the deputies and removed Hunt from his cell. The soldiers took him outside, where he was beaten and fatally shot. An off-duty captain in town rode back to the fort to report the events. No action was taken until 11:00 p.m., at which time beds were checked and all soldiers accounted for.

Private Miller died on April 27 and was buried in the post cemetery the next day with full military honors. Hunt was buried in the City Cemetery (now Mountain View Cemetery), with other gamblers paying his burial costs and providing a headstone. The county attorney protested Colonel Compton’s failure to control his troops or do anything about the slaying. Word of the murder reached President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901), who directed the Secretary of War, Redfield Proctor (1831-1908), to investigate.

Meanwhile, a Walla Walla court considered the case against six soldiers, but failed to convict when Sheriff McFarland could not identify the wrongdoers. However, in June 1891 an army court martial gave three soldiers dishonorable discharges and time in Alcatraz Penitentiary for the killing. Colonel Compton was suspended from service at half pay for three years, suspended in rank, and removed from duty for his failure to control his troops and to investigate the slaying. President Benjamin J. Harrison later reduced his sentence to two years at half pay, then lifted the punishment entirely in January 1893, remitting the remaining eight months of suspension. Colonel Compton, who had a distinguished record before the 1891 events, returned to his regiment and went on to serve in the Spanish-American War. He earned promotion to brigadier general shortly before retiring.

Last Years of the Fort

Fort Walla Walla became an underused installation in the 1890s, and recreation and sports assumed a more important role in the life of the troops stationed there. Polo became popular in the 1890s, with players from the fort going up against teams from as far south as San Francisco. The Sixth Cavalry served at the fort during this time, and despite War Department threats to close the post in 1897-1898, it remained open.

In 1902, four Ninth Cavalry Troops came to the fort from duty in the Philippines. The Ninth Cavalry, a famous unit of Buffalo Soldiers, had 16 white officers commanding 375 blacks. During its stay of more than two years, the unit dwindled in size, leaving only a small force. In January 1904 the War Department again proposed closing Fort Walla Walla, once more without success. The Ninth Cavalry disbanded in 1905 and the Fourteenth Cavalry, also a black unit, replaced it and served at Fort Walla Walla until 1908, with its main responsibility being the maintenance of law and order.

The fort finally closed on September 28, 1910. It was temporarily used as an emergency replacement for Saint Mary’s Hospital after that facility was destroyed in a fire on January 27, 1915. When Saint Mary’s moved to their new hospital in September 1916, a caretaker force took over the fort. In 1918 two batteries of the 146th Field Artillery (National Guard) trained there under the command of Major Paul H. Weyrauch (1874-1937). Interestingly, Weyrauch had served at the fort in 1904 as a second lieutenant. In 1908 he had retired to Walla Walla, but was recalled to active duty in 1917. About 260 men trained at Fort Walla Walla for duty in World War I, then departed for Camp Greene, North Carolina in October 1918 before being sent to France.

From Fort to Hospital

After brief use by the public health service in 1920, the decision was made to convert Fort Walla Walla to a tuberculosis hospital serving veterans in the Pacific Northwest. In August 1921 buildings not needed for the hospital were demolished and 14 buildings rehabilitated for hospital use. Work started in November of that year on a new ambulant ward. Contracts were issued for additional facilities, such as a heating plant and a laundry, but severe winter weather delayed construction until February 1922.

The medical facility was completed by May of 1922 and formally opened on June 4. Buildings that had once been barracks became hospital wards; personnel working at the hospital lived in the former officer and NCO quarters.

A Hero Returns

Jonathan M. Wainwright (1883-1951) was born at Fort Walla Walla, where his father, Lieutenant Robert Powell Page Wainwright (1852-1902), served. The younger Wainwright would attain the rank of general and become a hero during World War II for his actions in defending the Philippines. In November 1945, just months after his release from a Japanese prison camp, General Wainwright made a dramatic visit to Walla Walla and the place of his birth. The city honored its native son with ceremonies, speeches, and a parade.

The Fort Walla Walla medical facility was expanded to become a general medical hospital in 1959, and outpatient services were started in 1990. In 1996 the Veterans Administration renamed the facility the Jonathan M. Wainwright Memorial VA Medical Center. It continues (2011) to provide medical care to area veterans, having survived over the years additional attempts at closure.

Historic Fort Walla Walla Today

A number of original fort buildings survive and effectively recall the cavalry era, taking visitors back to an earlier time. The Fort Walla Walla district has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, along with 17 of its buildings. Fifteen are on Medical Center property and two on city property. They are best seen on a walking tour beginning near the visitors' parking area.

On the south side of the parade ground, the first stop is Building 7, an NCO quarters built in 1858 that today serves as the medical center's police headquarters. Next are two officer's houses (48 and 49), built in 1888. Continuing along this side are four duplex officers' quarters dating from 1858. At the east end of the parade field is Building 1, the commanding officer’s residence, which was built in 1877. These officer’s quarters have been used for medical-staff housing, but were vacant in 2010.

In the center of the parade field stands a statue of General Wainwright. To the north are Buildings 68 and 69, two large former enlisted barracks dating from 1906 that have been rehabilitated into medical facilities.

Additional fort structures are located away from the parade field. Building 40 near the chapel was originally a magazine, built in 1883. Buildings 63 and 65 house shops, and are north of the former enlisted-men's barracks. At the entrance to the medical center are Building 31, which housed stables and was built in 1859, and Building 41, a granary dating to 1888.