On April 4, 1953, the section completed in the first phase of building Seattle's Alaskan Way Viaduct opens. The viaduct runs along the central waterfront between Railroad Way and Western Avenue. Subsequent phases of construction will extend the State Route 99 bypass route north to Aurora Avenue via the Battery Street Tunnel and south to E Marginal Way via an extended viaduct structure, an at-grade roadway, and an overpass at the Spokane Street Viaduct. The viaduct offers the first limited-access route through Seattle and removes state highway traffic from city streets. A huge celebration featuring vintage cars, entertainment, speeches, and a ribbon cutting opens the viaduct to traffic.

Beginning the Work

Construction of the first phase began on February 6, 1950, when crews from McRae Brothers began work on the first section of the project, a side-by-side elevated roadway between Western Avenue and Pike Street. The structure angled along the hillside between Battery Street and Alaskan Way, joining up with the waterfront street at Pike Street.

At Pike, the roadway became double-decked and followed Alaskan Way along the central waterfront. Alaskan Way had a wide right-of-way because the street had originally been created as a thoroughfare, known as Railroad Avenue, for the multiple railroads that served the piers. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, each of the transcontinental railroads and several regional lines had laid tracks on trestles along the central waterfront.

During the first half of the twentieth century, cargo handling and some of the railroad operations gradually moved to the north and south ends of Elliott Bay. By the time, in 1936, the seawall between Madison and Bay streets was completed and the land behind it filled in, some of the tracks had been removed and most of the rest were placed adjacent to the newly built Alaskan Way. This left a large swath of land to the east of Alaskan Way available for the Alaskan Way Viaduct.

At the southern end of the structure, on- and off-ramps connected the elevated roadway with 1st Avenue S at S Railroad Way, a diagonal street near today's Royal Brougham Way. At the northern end of the viaduct, a northbound off-ramp took traffic to Western Avenue and a southbound ramp allowed traffic from Elliott Avenue to enter the viaduct.

The elevated portion on the central waterfront included access points for four ramps to and from downtown, but only two of these would be built, and not until the 1960s. Later construction projects would connect the viaduct to Aurora Avenue via the Battery Street Tunnel in 1954 and to E Marginal Way via the southern extension of the viaduct and an at-grade roadway in 1959.

A Festive Ribbon-Cutting Affair

The Automobile Club of Washington and the Junior Chamber of Commerce organized the festivities celebrating the viaduct's opening in April 1953. A procession of what the Post-Intelligencer termed "ancient automobiles ... some the vintage of the first President Roosevelt" brought Seattle Mayor Allan Pomeroy (ca. 1907-1966), Seafair Queen Iris Adams, Department of Highways Director William A. Bugge (1900-1992), City Engineer William E. Parker, Fred G. Redmon (1897-1983), chair of the Washington State Highway Commission, and other dignitaries ("Colorful Ceremonies") along the northbound deck of the viaduct to its north end, near today's Pike Place Market.

The crowd, which braved blustery weather to celebrate the opening, enjoyed performances by the Seattle Police Department color guard and drill team and an orchestra hired by Ivar Haglund (1905-1985), waterfront entrepreneur and booster. Can-can dancers meant to evoke the Klondike Gold Rush era also performed.

Seafair Queen Adams ducked away during the speeches and reappeared before the crowd seated on a dog sled pulled by 8 Alaskan Huskies. Legendary dog musher Leonard Seppala (1877-1967) drove the team, depositing Adams and an oversized pair of scissors at a ribbon across the roadway. Adams and Pomeroy cut the ribbon, with a bit of assistance from Automobile Club of Washington president D. K. MacDonald's pocket knife. Pomeroy told the assembled crowd and radio and television audiences, "This viaduct will lead to even greater things, perhaps to one-way streets and still more projects to relieve our traffic congestion" (Heilman, 2).

Traffic, led by the procession of ancient automobiles, continued on to the Western Avenue exit, turned around, reentered the viaduct via the Elliott Avenue on-ramp, and continued on to the southern end.

Loving Alaskan Way Viaduct

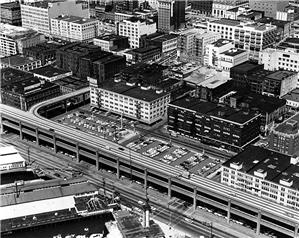

The city's newspapers joined in the mayor's enthusiasm. The Seattle Times gushed, "V-Day was Viaduct Day and Victory Day; a triumph in double measure!" (Heilman, 1). The Post-Intelligencer ran several pages of photos and accompanying articles. One photo caption read, "In this sweeping aerial photograph, the viaduct looms like a royal necklace across the bosom of the Queen City of the Pacific Northwest" (Hoffman).

Likewise, the state Department of Highways' newsletter featured an article about the opening that lavished praise on the project. Highways' employee Kay Conger wrote, "The next time you are in Seattle be sure to take a trip over this giant double-deck structure which allows traffic to soar over the maze of railroads along the waterfront and bypass the congested streets of Seattle's business section. From the upper deck (north bound), you'll enjoy a breath-taking view of Elliott Bay and the Olympics to the left, and of Seattle's towering skyline on the right. From the lower (south bound) level, you'll catch glimpse the picturesque waterfront, the ships from far-off lands, the long line of wharves and piers, all the panorama of shipping and commerce" (Conger, 2).

Though the viaduct terminated at busy city streets on both ends, it quickly became a popular route around downtown. In its first year, daily traffic reached 19,000 vehicles. Once the Battery Street tunnel opened, in 1954, and the southern extension connected the viaduct route to E Marginal Way, in 1959, traffic jumped to 37,000 vehicles per day. In the next decade it would reach 88,000 per day just before the opening of Interstate 5 in the mid-1960s.