On August 18, 1928, fire sweeps through the coal mining town of Ronald in Kittitas County, destroying 32 houses, several businesses, and leaving 136 persons homeless. Bert Pellegrini, age 49, the bootlegger responsible for this calamity, was making a batch of moonshine liquor in a hidden room underneath the Falcon Pool and Dance Hall when his 250-gallon still explodes. Fueled by alcohol, a large portion of Ronald is in flames within minutes. The fire, fanned by strong winds, spreads from the town into the trees and scrub brush, threatening the neighboring community of Roslyn, less than two miles distant. Some 2,000 miners, railroaders, firefighters, and citizens from nearby towns manage to check the fire’s progress less than a quarter mile from a large powder house where explosives are stored. Thanks to their valiant efforts and the sudden abatement of the wind, Roslyn is saved from disaster. Damage to Ronald is estimated to be $100,000. The only fatality is Bert Pellegrini (1879-1928), who is severely burned and dies in a Cle Elum hospital.

A Kittitas County Coal Town

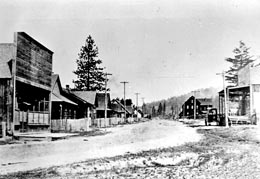

The town of Ronald, two miles west of Roslyn in northwest Kittitas County, was created in the late 1880s as a supply center for miners working in No. 3 coal mine for the Northern Pacific Coal Company (renamed Northwestern Improvement Company in 1899), a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The town was named after Alexander Ronald, the superintendent of the mining operation.

The mines at Ronald, Roslyn, Jonesville (also called Beekman), and Cle Elum were the main supply of coal for Northern Pacific Railroad's steam-powered locomotives. During the peak coal production years of the 1920s, this company town had a population of approximately 750.

Whiskey and Fire

Bertholomes "Bert " Pellegrini (also spelled Pelligrini) was the proprietor of the Falcon Pool and Dance Hall in Ronald. A town resident for only eight months, he also owned and operated the Donadio Garage. At 2:30 p.m. on Saturday, August 18, 1928, Pellegrini was distilling a large batch of moonshine whiskey in a hidden chamber beneath the pool hall. (Prohibition became law in Washington state in 1916.) During this process a 250-gallon vat of alcohol exploded. Somehow he managed to escape from beneath the burning building and stumble home. His wife, Margaret, called a neighbor, who drove Pellegrini, severely burned, to a hospital in Cle Elum.

Fueled by the alcohol, the flames immediately consumed the wooden building, spread rapidly through the surrounding businesses and then to miner's houses. Gasoline in storage at the General service station further fueled the flames and before long the entire lower portion of the town was ablaze. The Cle Elum Fire Department rushed to the scene with water pumps, saving many houses that otherwise would have been destroyed. Strong winds fanned the flames and blew burning shingles and embers into the tinder-dry scrub brush and trees southeast of Ronald. There had been no rain for weeks and fire spread rapidly down the valley in the direction of Roslyn.

Fighting the Flames

By now, the entire region had been alerted to the peril. All the coal mines from Jonesville to Cle Elum were shut down and the miners sent to fight the wildfire advancing toward Roslyn. They were joined by hundreds of railroad workers, firefighters, and citizens from nearby communities. Some 2,000 people joined together in the desperate attempt to save Roslyn and possibly Cle Elum from destruction. Of major concern was the huge stone powder house, located half-a-mile northwest of Roslyn, where a considerable quantity of explosives was stored. A Northern Pacific freight train was moved into position on a spur to carry away the explosives in case the fire could not be controlled.

Roslyn Fire Chief Percy Wright brought pumper trucks into the area, but without an adequate water supply nearby, the equipment was relatively useless. Firefighters dug wide firebreaks, lit backfires, repeated their efforts and then withdrew, waiting for the flames to reach the outskirts of Roslyn, where there was a plentiful supply of water. Late in the evening, however, the wind suddenly died down and crews managed to check the fire's advance a short distance from the powder house. State Fire Warden Edward T. Lanigan enlisted 75 volunteers to patrol the hills between Ronald and Roslyn throughout the night, watching for hot spots that could flare up.

Death of a Bootlegger

Meanwhile, Bert Pellegrini lay in a Cle Elum hospital in critical condition. Delirious with pain, he muttered interminably about his moonshine still exploding and the terrible fire. Pellegrini died shortly before midnight, mumbling: "I've got to get out that hundred gallons today" ("Wind Shift Saves Roslyn Like Fate"). On Monday, August 20, 1928, a funeral service for Pellegrini was held at Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Roslyn with burial at Eagle's Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Margaret, and son, Paul.

Only one other person was injured in the fire. George Radabaugh, a miner from Roslyn, was trapped and suffered burns when trees and brush behind him burst into flames.

On Sunday, April 19, 1928, Kittitas County Sheriff George "Scotty " Gray investigated the smoldering ruins of the Falcon Pool Hall and discovered a 100-yard tunnel, leading from Pellegrini's secret underground distillery, to a storage chamber that held 23 50-gallon barrels of "white mule " whiskey, ready for delivery. Conveniently, the chamber was located beneath the Donadio Garage, owned by Pellegrini. A shaft, equipped with an elaborate system of block and tackle, opened into the now defunct building where bootleggers could load trucks with barrels of moonshine for transport to Seattle and Tacoma. Numerous barrels of mash and aging liquor were stored in other tunnels emanating from the distillery.

To Relieve and Rebuild

The fire in Ronald had gutted the business district, except for the Modern Bakery, and destroyed 32 houses, leaving 50 adults and 86 children homeless. The Ronald Improvement Club immediately took charge of the relief work, providing food and temporary shelter. The American Red Cross, United Mine Workers of America, and various local civic organizations joined in the relief efforts, collecting food and clothing and raising money to care for those families left destitute by the fire. A survey by the Washington State Insurance Commissioner's office estimated damage to the community to be approximately $100,000. Few people carried insurance, however, and many cached their savings in or under their houses rather than trust the banks. The coal mines in Ronald remained in operation and the Northwestern Improvement Company soon rebuilt the town.

By the early 1950s, the Northern Pacific Railroad had replaced most of their steam-powered engines with diesel-powered locomotives, which led to the decline of coal mining in the area. All the mines were eventually closed in the early 1960s and the Northwestern Improvement Company sold its holdings. In 2010, the unincorporated community of Ronald, termed a "census-designated place " by the U.S. Census Bureau, had a population of 308 persons.