On September 5, 1928, the Seattle City Council passes Ordinance No. 55985 prohibiting dance marathons and similar endurance contests and declaring an emergency. Dance marathons were Depression-era human endurance contests in which couples danced almost non-stop for hundreds of hours (as long as a month or two), competing for prize money.

Going Squirrelly

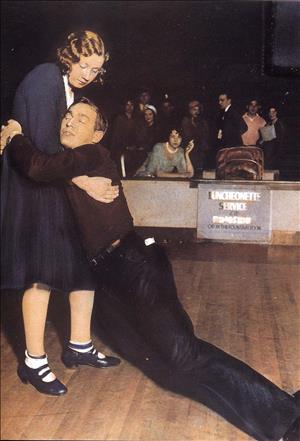

Dance marathons were popular during the 1920s and 1930s. Contestants, competing for prize money and attempting to set world records, were required to remain on their feet, in motion around the clock, with only brief rest periods each hour. Audiences were encouraged to root for their favorites and stay as long as they liked. Contestants typically experienced sleep deprivation-induced psychosis (referred to in the dance marathon business as “going squirrelly”). During these periods they laughed, cried, plucked imaginary objects from the air, hallucinated, and sometimes attacked other contestants.

Seattle mounted its first (and, as it turned out, only) dance marathon within the city limits from July 23 through August 11, 1928, at the Seattle Armory. The 1920s fad for setting world records, as well as the relative novelty of the event, resulted in prominent coverage in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

As the competition wore on and the contestants’ conditions deteriorated, the public spectacle generated both fans and critics: “ ‘My husband says I’m waiting to see one of ‘em drop. I been here three days now, and haven’t even got my wash out this week. Last of the week time enough with this show goin’ on,’ ” confessed one audience member (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 8, 1928). “No, not a show to give one pride in one’s race, or time or city. A shameful exhibition, indeed, of warped and limited mentalities drawing frail and unhealthy bodies to the breaking point,” complained another (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 8, 1928).

A Sad Situation

Eleven days after the dance marathon ended, the fifth-place female finisher attempted suicide by turning on the gas in her room at the Virginian Apartments, 2014 4th Avenue, Seattle. Gladys Lenz had made the papers mid-marathon when her partner, E. H. Martineau, “suddenly smacked his partner in the jaw … leaped over the rail of the dance floor and was caught as he dashed into the street. He was delirious from lack of sleep … Gladys Lenz was staggered by the blow” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 30, 1928).

Lenz continued on with another partner, eventually winning $50. Worn down from the ordeal and despondent over her inability to reclaim her infant son from her ex-husband in Yakima, Lenz tried to take her own life.

Although Lenz was rescued and survived the ordeal, public reaction was swift. “Chief of Police Louis J. Forbes and Dr. E. T. Hanley, city health commissioner, said the action of Mrs. Lenz should give added impetus to the passing of an ordinance, now being framed by councilman Robert B. Hesketh, to bar future marathon dances from Seattle” (The Seattle Daily Times, August 22, 1928).

A Dance-Marathon-Free Zone

City Council President Hesketh introduced the bill (No.46230) on August 24, 1928. It passed as Ordinance No.55985 on September 4. Mayor Frank Edwards signed it the following day.

The ordinance required, in part, “Any endurance contest given as provided herein shall terminate at or before midnight of the day on which it begins” (Section 3). This automatically ruled out dance marathons, which lasted weeks or sometimes months. The ordinance remained on the books until superseded by Ordinance No. 102843 on December 18, 1973. Seattle’s ordinance prohibiting the contests was the first such ordinance within the Pacific Northwest and one of the earliest in the nation.

Seattle thus remained a dance-marathon-free zone throughout the 1930s. The contests, also called Walkathons, continued to be mounted across the state, including in unincorporated King County just north of the city limits.

On March 13, 1937, the state of Washington prohibited dance marathon statewide.